| |

|

St Mary,

Banham

|

|

A large, prosperous south

Norfolk village, fat and sleepy like an old cat

on this day of high heat in August 2018, and the

famous view of its parish church of St Mary is

from the green - the village sign, the war

memorial, and then that magnificent spire lifting

to heaven. It rises more than 40 metres, and is

made of ribbed lead, very similar to the one over

the border at Hadleigh in Suffolk. It had been a

long time since I last visited Banham church,

long enough ago for its size and presence to have

surprised me. The building is pretty much all of

a piece, early 14th century. The Victorians

brought the east window, which Sam Mortlock

thought somewhat excessive in its exuberance, but

the wealth of flowing tracery elsewhere in the

church holds up well against it. You step into a large, well-kept

jewel. Although, inevitably, there was a massive

Victorian restoration here, there is still a

feeling of simplicity, with brick floors and

slightly cluttered furnishings, all overshadowed

by a magnificent west end organ. High above, the

roof bears the date 1622, and the little George

III royal arms look like a postage stamp above

the high tower arch. The star of the show is the

luscious range of 19th and early 20th Century

glass, much of it the work of Powell & Sons.

The 1857 east window, unusually, is a cavalcade

of geometric designs in pressed glass, with at

its centre a crucifixion. The artist was John

Clayton, a vigorous scene, his watchers looking

up in an agony, showing what he was capable of

before Alfred Bell came along and made him

serious. It is reminiscent of the work of Robert

Bayne in the same decade.

|

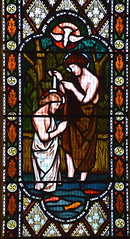

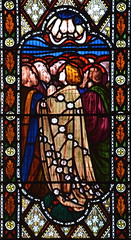

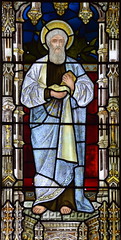

The other 19th Century Powell &

Sons glass is to the designs of the great Henry Holiday.

The earliest echoes the style of the east window, with

medallions of the Baptism of Christ, the Adoration of the

angels at the Nativity, and the Ascension of Christ. The

best, in the south aisle, depicts gorgeously rich figures

of the four Evangelists, each in their own light over two

windows.

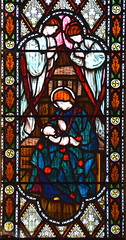

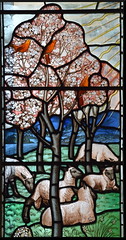

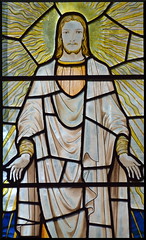

The richness of these was echoed

half a century later by a Powell & Sons window of

1936, which is probably the freshest and most memorable

thing in the whole church. The risen Christ stands

between two lights, one depicting spring with sheep

grazing beneath an apple tree in blossom, the other

autumn with the tree in fruit above rabbits and birds. It

would be interesting to know who the artist was. The

window beside it of the Presentation in the Temple is by

Kempe & Co, and seems curiously out of place as if

simply not speaking the same language, but then I've

never been a fan of Kempe glass.

The earliest English glass is in

the chancel, a range of the twelve disciples and a Tudor

arms all in a pre-Ecclesiological style. It probably

dates from the 1830s, and has not worn well, the painted

details have long since faded and all that remains are

mosaics of coloured glass suggesting human figures.

However, there is a very good 16th Century continental

image of the Blessed Virgin and child in the north aisle,

collected from elsewhere and set here in the 1960s. In

the east window of that aisle is a single 19th Century

panel depicting Christ with Martha and Mary at Bethany,

which seems so odd to find in isolation that I think it

may too have come from elsewhere.

At the east end of this

aisle lies a wooden knight, life-size and rather

severe in his simplicity inside his tomb recess.

He is popularly believed to be Sir Hugh Bardolph,

founder of the church, but as Pevsner drily

notes, given that Bardolph died in 1203 and this

effigy is early 14th Century, it is a bit too

much of an afterthought. Woodwork of a later

time surmounts the font on its stepped pedestal,

a grand gothic font cover of the 1860s that might

take its inspiration from the Albert Memorial.

The screen came next, and by the end of the

century the two richly carved reredoses in the

sanctuary and the north aisle chapel.

On this day of bright sunshine on a day in high

summer, the temperature dipping up into the

thirties, this felt a proud, confident place, a

real statement of 14th Century confidence coupled

with 19th Century piety and energy. But I

remembered being here once before, some fifteen

years ago, late on a December afternoon. The low

sun made the shadows long, and inside the church

the south aisle windows glowed as if they were on

fire as the nave and chancel darkened. And as I

sat there, the day faded. I could hardly see the

settings on my camera any more, but Christ in the

apple orchard still glowed fiercely, the

brightest of the jewels, as if on its own holding

back the sinking sun. And then, as the afternoon

deepened, the windows around darkened, like stars

fading, and this was the last to go out. |

|

|

|

|

|