| |

|

All

Saints, Bawdeswell

|

|

Nothing

lasts forever. At a quarter nine in the evening

of the 6th November 1944, a Mosquito bomber

returning home from a raid on Gelsenkirken iced

up as it descended through cloud near the small

Norfolk town of East Dereham. The plane came

spiralling down towards the Norwich to Fakenham

road, and crashed right into the middle of the

village of Bawdeswell. Fortuitously, it landed

right on the village church, which it completely

destroyed. The wrecked building had been an early

Victorian church by John Brown, which itself had

replaced an 18th century mock-classical building.

The tower of the medieval All Saints had

collapsed into the church and destroyed it in

1739. As often in East Anglia, neglect of a

structure principally built of flint had led to

its demise.

Over

the centuries, English parish churches have

always been extensively rebuilt, but the process

just continued for longer at Bawdeswell than it

did elsewhere. When the villagers came to choose

a design for their new church, we may assume that

they at least looked at something modernist -

this was, after all, the 1950s, and the Festival

of Britain was encouraging the clean lines and

light spaces that would flush away the neurotic

elaboration and darkness of much of the

architecture of the first half of the century.

Barely a hundred miles off, one of the great

buildings of the century was going up in

Coventry, where the city's cathedral, formerly

the parish church of St Michael, had been gutted

in the blitz.

|

It is worth

pointing out that many surviving early 19th century

parish churches like the one destroyed by the returning

bomber have not worn well. Coming before the flowering of

that century's architecture, they tend to be dark and

dingy, their fittings are anachronistic, even absurd, and

there is no reason to think the parishioners of

Bawdeswell had a special fondness for the lost building.

Indeed, what they chose to replace it seems almost a

direct reaction. Rejecting both Gothic and Modernist

forms, they chose something that is basically

neo-classical, in the style of the 18th century but

perhaps also with the flavour of New England. The

materials, if you please, would not be concrete and steel

but Norfolk flint and shingle.

The church

sits near the centre of the village, set back politely

from the street behind a small green and what appears to

be intended as a carriage drive. A number of the old

headstones were reset on the western side of the

churchyard, and another intriguing survival is a large

cross set up beside the porch. It's inscription reads When

this church was destroyed on November 6th 1944 this cross

remained standing on top of the bell tower. The cross was

originally erected in loving memory of John Romer Gurney

who died March 29th 1932.

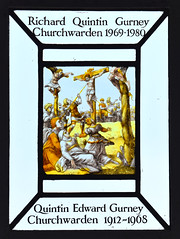

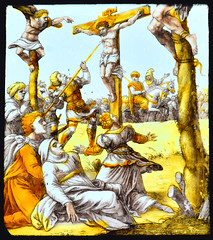

All Saints

has the homogenity that echoes the restored Wren City of

London churches. The mock-classical portal, which should

overwhelm, doesn't. The bell fleche and clock stage were

completed in the 1990s, and you step inside to a space

full of light, the simple wooden furnishings splendid

under the mainly clear glass set with roundels and panels

of continental glass, some 17th Century, some 20th

Century copies.

The architect was James

Fletcher Watson who, in his nineties, could return to the

fiftieth anniversary celebrations, and survey his work

with pride. At the time it was built, and in the decade

or so afterwards, his work here was scoffed at as being

in what Betjeman once described as 'ghastly good taste',

but the fact is that it has stood the test of time very

well indeed. At this distance, there is a

Festival of Britain cleanness and light to its lines, and

although it is a very simple building it resists the

blandness that would emerge in the 1980s

shopping-centre-school of neo-classical, as found at,

say, Quinlan Terry's Brentwood Cathedral.

To

emphasise the early 18th Century intentions of the

interior, Fletcher Watson insisted on a three decker

pulpit, which the parish were at first uncertain about.

They gave in when he designed one that could be easily

dismantled if necessary, and there it is, still in place

today. An organ gallery is tightly crammed into the west

end, perhaps the only not-entirely happy moment of the

interior, but in any case the eye is quickly drawn to the

grandeur of the column-flanked apse, the altar serious

and alone in the stark whiteness. One touching memorial

records the plane crash itself, recording the names of

James Maclean and Melvin Tansley, the pilot and co-pilot.

It is made from a piece of the recovered fuselage.

The

overall cost of the rebuilding and furnishings was

slightly less than £20,000, about half a million in

today's money, which seems very reasonable. Most of it

came from the War Damage Reparations Fund.

| In fact, no East Anglian

parish church destroyed in the Second World War

would be replaced by a determinedly modern, or

modernist, building. Some were not

replaced at all of course, for there seemed

little point in rebuilding those lost in the

Norwich blitz. The city already had enough

little-used worship spaces. Where churches were

replaced, there was usually a looking back to

what was there before. At Chelmondiston in

Suffolk for example, Basil Hatcher replaced the

destroyed church in textbook Decorated Gothic.

More famously, at Great Yarmouth, the vast civic

church of St Nicholas was rebuilt by the

eccentric Stephen Dykes Bower as if none of the

centuries from the 16th and 20th had even

happened.

And so in

retrospect it was never likely that the

Bawdeswell parishioners would be feverishly

dialling up the steel and concrete manufacturers.

And yet neither had they any reason to mourn for

the building they had lost. What they

chose instead is rather wonderful. All Saints is

a cool, bright, welcoming place, a refreshing

delight, a must see.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, March 2018

|

|

|