| |

|

St

Leonard, Billingford

|

|

If I told

you that St Leonard is an ancient treasure house

in a beautiful hill top graveyard, that you reach

it up a narrow track, that on a day in late

spring there is bird song all about and a

windmill turning lazily in the valley below, it

would make you want to visit it. If I told you

that to get to the narrow track you would need to

negotiate one of Norfolk's most hellish roads,

the A143, with juggernauts hurtling towards the

ports and cars overtaking crazily, it would

probably make you less keen. At one time, the

church was difficult to visit for another reason:

incredibly, visitors, weren't welcome. When I

first came this way in 2005, the Scole benefice

had a reputation for not allowing keys to be

borrowed. But all that has changed. |

We headed back to

Billingford in May 2007. We'd been border-hopping,

working our way down the Waveney Valley visiting churches

in both counties. We'd found all the Suffolk ones open,

and standing in Oakley churchyard, gazing out across the

valley to Billingford windmill, the copse of trees that

enclose St Leonard's graveyard on the hill above seemed

most enticing. We headed down the hill and across the

narrow bridge, and climbed again the track to the church.

The pretty church

revealed itself from behind the trees. The tower is

capped slightly above nave level. Was it ever finished?

Simon Cotton tells me that there was a bequest in 1527

for its construction - perhaps it was only begun before

the Anglican Reformation intervened. The nave and chancel

are a pleasing combination of Dec and Perp, and those big

red roofs glowed handsomely in the sunshine that hadn't

been predicted by the forecasters.

I was optimistic,

and not just because of the sunny day. I had been told

that, now, all the churches in the Scole benefice are

either open or have keyholder notices. I think this may

be due in part to the Diocese of Norwich having appointed

an Open Churches Officer who happen to live in Scole. His

name was Ralph Barnett, and although he had now moved

onto another challenge he seemed to have made a big

difference.

| There had

also been the appointment of a new and

enthusiastic Rector to the Scole benefice. Quite

by coincidence, we met both of them outside St

Leonard; we parked on the grass verge, and found

they were parked behind us.The Rector, a bluff

Yorkshireman, answered our request for access

with the question "why, are you collecting

the silver?" to which the obvious answer was

"yes, and we only need this one for the full

set!". The freemasonry of English humour,

which must baffle any foreigner, was complete. For some reason,

this exchange was enough for Ralph to recognise

me. We'd previously had an e-mail correspondence.

It is always reassuring to meet people who are

enthusastic about the life of medieval churches,

and Ralph's zeal is infectious. I could easily

see how he had got the good people of the Waveney

Valley thinking in a new way about how their

church could provide a welcome.

|

|

|

The great majority

of Norfolk churches are, in fact, open every day, but

those that are kept locked tend to huddle together as if

in mutual misery - the area south of Norwich, the

Thetford area, and, until recently, this place. It has to

be said that St Leonard still isn't actually open, but it

is certainly a step in the right direction to be let in

without suspicion.

We stepped into a

delightful, rural, rustic interior, quite the loveliest

of little churches. It feels smaller inside than out. The

19th century restoration seems to have been more of a

reordering than a refurbishing. The medieval font, in the

typical East Anglian design, leads to medieval bench ends

with grotesque faces on the poppyheads. An elegant 17th

century font cover is matched by a pulpit of the same age

on the other side of the range of benches.

Some ancient glass

is largely heraldic, although there are fragments of

other late medieval themes set around them. A great

curiosity is the wall painting on the south wall. It

appears to show several different scenes, perhaps once

part of a larger scheme. In the clearest, several figures

stand in a doorway. Could it be one of the Works of

Mercy?

The pretty screen

is very small, just two double lights either side of the

centre, but it is imposing in this tiny space. The

corbels that hold up the roofs are old too. It is all

very pleasing; no outstanding treasures, but a harmonious

whole bringing together elements of the late Medieval and

the early Modern, crystallised sensitively by the

Victorians. It is delightful.

One of the young

men who set out from this tiny parish for the killing

fields of the First World War received the Victoria Cross

- as, indeed, did a soldier from neighbouring Scole.

Billingford's was a man called Flowerdew, a name

remembered elsewhere in the church from an earlier

generation.

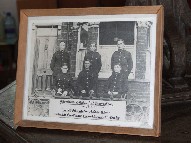

| Mortlock

became quite emotional about him, recalling

Wilfred Owen's words Was it for this the clay

grew tall? O what made fatuous sunbeams toil to

break earth's sleep at all? Even more moving

than this is the framed photograph set on the

font. Six of the young men of Billingford choir

pose proudly in their uniforms before heading off

to war. Only two survived: Sam Fisher and Leonard

Bloomfield in the front row. The names of the

other four are listed on the parish war memorial.

Four out of six being killed may seem a lot, but

this was roughly par for the course for the 'Old

Contemptibles' who signed up at the very start of

the First World War.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, June 2005, updated May 2007

|

|

|