| |

|

St

Margaret, Burgh St Margaret

|

|

As

you head eastwards, Norfolk falls away behind

you. The landscape simplifies, as though the wind

from the grey North Sea has scoured it of

anything inessential. In late winter, with the

fields ploughed and the caravan parks empty, it

can seem a tabula rasa, an empty slate, cleansed

and waiting.

The village is called Fleggburgh, but the parish

is Burgh St Margaret. It lies a few miles inland

from the sprawling resorts of Yarmouth, Caister

and Hemsby, but its fate is very much tied to

theirs. The area's biggest employer is the

leisure industry, and the east Norfolk towns and

villages seem empty outside of high summer. And,

just as the seaside towns rose to prominence in

the late 19th century, so there was a knock-on

effect in the hinterland. Outside of Norwich,

this is the only part of Norfolk where the

population was actually rising in the 1870s and

1880s, and this pretty church underwent a major

renewal, an almost complete rebuilding, at the

hands of Diocesan architect Herbert Green. |

Along with

his predecessor Richard Phipson, Green bestrides the

landscape of church Victorianisation in East Anglia. The

bodies of their work are considerable, and it wasn't just

their own plans; anyone else's work would also have to

cross their desks for them to cast a cold eye upon it.

Their enthusiasms were as different from each others as

it is possible to be, I suppose. Phipson was a

technician, with an eye for detail. In restorations, his

innovations blend fairly seamlessly into the medieval,

which sounds good, but often leaves a rather dour,

characterless atmosphere. Sometimes he went mad,

producing extraordinary spires on a couple of churches in

the Stowmarket area, and he could be very impressive on a

grand scale, such as the complete rebuilding of St Mary

le Tower in Ipswich.

Herbert Green, on the other hand, was a Victorian first

and an medievalist second. Sometimes it is hard to see

the medieval origins at all behind his rebuildings,

scourings and facades. Here at Burgh, he built a

'Perpendicular' nave and a 'Decorated' chancel and tower,

which is of course exactly the relationship you find at

so many rural medieval churches in East Anglia. It's just

that here it isn't real - to all intents and purposes,

this is a faux medieval Norfolk parish church.

| The

harsh blue knapped flints would look even worse

if it wasn't for the thatching that softens them.

One curiosity - note how high the gables at the

east end of the nave and chancel rise above the

thatch. That on the nave is even higher than the

bell windows of the tower. This must be because

they are substantially the medieval originals.

But nothing else is, I think. The red-brick

arching to the windows helps a bit, but really

this is a severe exterior, and knapped flint on

such a scale would soon fall out of fashion, to

be replaced by the cosiness of the Arts and

Crafts movement. We can already see this

happening here, for there is a cottage dormer

window above the porch to be thankful for. It is

here for a reason, because it lights the little

gallery tucked into the roof space. |

|

|

Inside,

everything is Herbert Green's, pretty much. There is no

tower arch, just a doorway, through which you can access

the gallery. The furnishings are all of a piece, and the

font is in the style of the 15th century. Green was very

fond of Norman fonts, so it is interesting that here he

chose a font to match the (imitation) Perpendicular nave

rather than the (real) Norman south doorway. The stone

reredos is perhaps more in Green's heavy style.

There are a couple of items of interest. A figure brass

of 1608 remembers Richard Burton, the minister of this

parish; it is remounted in a marble setting on the

chancel wall. Opposite it is a moving memorial to George

Thompson Fisher, who died in WWI. He was son of the

Rector here who had overseen Green's rebuilding, and who

was, incidentally, the very last Bishop of Ipswich.

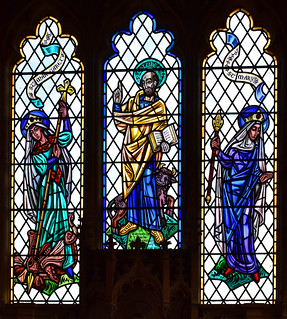

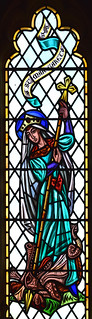

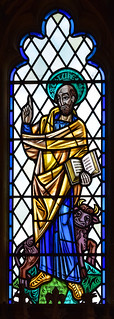

The jewel in the crown of all this is the

east window of 1968 by Paul Jefferies, in the uninhibited

dynamic style of the time. It features the figures of St

Margaret, St Luke and the Blessed Virgin. St Luke's bull

looks a cheery sort, and St Margaret dispatches her

dragon with aplomb. Mary, who is shown as the Queen of

Heaven, is a little less vigorous than the other two

figures. Her lack of an accompanying animal throws the

composition slightly out of balance, and you wonder why

she wasn't placed in the central light.

Simon Knott, March 2006, updated

November 2016

|

|

|