| |

|

St Mary,

Burston Your first thought on seeing it might be

that perhaps this is not one of Norfolk's more exciting

or interesting churches. A round tower fell in the 18th

century, and the parish could afford to do no more than

patch up the remains. After decades of neglect, the nave

and chancel were refashioned in an uncharacteristically

utilitarian manner by the Victorians, leaving a rather

barn-like structure. The nave walls, with their massive

Perpendicular-style windows and buttressing, look very

curious under the shallow tiled roof, but the scattering

of red brick at the west end gives it character, and the

whole piece is not unattractive in the tree-shrouded

graveyard. Internally, the church was converted for

community use in the 1990s, giving the nave the character

of a village hall. There was a further major

refurbishment and repair from 2013, thanks to a grant

from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

However, despite the battering, repatching and

refurbishing of the last couple of centuries, Burston

church is full of interest. It is open every day, and you

step in through the gloom of the rather austere Victorian

south porch into a church full of light. A light wooden

floor replaced the Victorian tiles, and, although none of

the nave furnishings were retained, the font is a decent

14th Century affair with characterful figures around the

stem. Above it on the west wall is one of Norfolk's best

James I royal arms, still in its original frame. The

chancel retains something of its 19th Century integrity,

some of the stencilling exposed from behind the limewash

which had concealed it in the 1960s when it had

deteriorated to such an extent that it had become

unsightly to eyes that in those days did not approve of

Victorianisation of this kind. The glass in the east

window is a good example of the more conservative strand

in 1930s stained glass, and it would be interesting to

know who the workshop was.

|

|

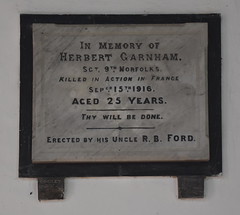

There

are memorials to two local boys killed in World

War One in the nave, and one of these is of

particular interest. It remembers Herbert

Garnham, killed on the Somme in September 1916.

He was 25 years old. Intriguingly, the

inscription records that the memorial was erected

by his uncle. This was because Herbert's

father had refused to allow a memorial to his son

in the parish church. The Garnhams were

participants in the Burston School Strike, a

violent dispute between the rector of this church

and the working people of the village. When

Herbert Garnham's father learned of the memorial

being placed in the church, he attacked it with a

sledgehammer, smashing it to the floor. For this,

he received a month in prison, and the memorial

was repaired and restored to the wall, although

you can still see the cracks in it today. So, what

was this disagreement that tore apart this small

rural community in the early decades of the 20th

Century? To answer that question you should look

immediately to the west of the churchyard, for

here on a patch of grass sits the world famous

Burston Strike School, a memory of what is

sometimes referred to as the longest strike in

British history.

|

In 1913,

Kitty and Tom Higdon, headmistress and senior teacher

respectively of the Burston Church of England village

school, came into dispute with the school managers after

Tom Higdon had been elected to the parish council. The

Higdons were Christian Socialists, and were widely

perceived as troublemakers. They refused to let the

children be taken out of school to help with the harvest,

or to do back-breaking, poorly-paid work like

stone-picking. Such employment was illegal, of course,

but it was the universal practice in rural areas at the

start of the 20th century.

The Higdons' nemesis was the Reverend Charles Tucker

Eland, Rector of St Mary. He was a clergyman of the old

type, an unchallenged authority figure in this parish

without a resident squire. Not surprisingly, he held

Victorian views of the relationships between the classes,

as did the majority of the tenant farmers. The 1870

Education Act had decreed universal education, but the

role of education was so often interpreted as preparing

the children for their place in the social order. Under

such circumstances, learning to read and write was

acceptable, but learning to think was positively to be

discouraged. It was expected that the boys of the parish

would become poorly-paid farm workers, and the girls

would go into service.

Tom Higdon was a popular figure with the local

farmworkers, and he championed their fight for higher

wages and better conditions. Universal suffrage for men

allowed him to top the poll in the Parish Council

elections, and the Reverend Eland came bottom, losing his

seat. But, crucially, he still led and controlled the

School Board. Within days, the School Board found an

excuse to sack the Higdons from their roles as

headmistress and senior teacher.

Twenty years earlier, that would probably have been the

end of the story. Twenty years later, it perhaps wouldn't

have happened at all. But this was a crucial moment in

European history. Far off, in Sarajevo, a single shot

fired at the Archduke Franz Ferdinand set in chain a

sequence of events that would lead to the Great War,

which would change rural East Anglia forever. It was also

to have an unforeseen effect on what happened next.

The Higdons set up an open air school on the village

green. Magnificently, the great majority of the poorer

families of the parish took their children out of the

village school and sent them to learn from the Higdons.

The establishment reacted. The Rector, shamefully,

expelled the striking families who held allotments on his

land, and he had their crops destroyed. Other families

were given notice to quit from their tied cottages.

However, these evictions were not carried through,

because the Great War had led to a serious shortage of

labour, and the tenant farmers simply could not afford to

lose their workers. The principles of the farmers were

not as strong as those of the farmworkers, or perhaps

they were merely pragmatic. In the event, the Strike

School survived and prospered, moving into a carpenter's

workshop that first winter, and then into a fully

equipped, brand new school funded by collections made by

Trade Union and Socialist organisations around the world.

The church school also continued, and by the 1920s the

two schools had settled down into an uneasy but workable

rivalry. The old order was falling away, the Reverend

Eland retired, and his replacement, Francis Smith,

supported both schools equally, giving religious

instruction in both. The Strike School lasted until 1939,

by which time the Higdons were both in their seventies.

After Tom died, Kitty gave up the school, and it closed.

The strike had lasted 25 years.

Today, the Strike School is a museum, but the village

green is still the focus for a national Trade Union rally

on the first Saturday of each September. The village

school continues to survive in the same buildings from

which the Higdons walked away a century ago. For many,

the main reason for visiting Burston today is the Higdons

and the story of Britain's longest strike. The Higdons

are buried side by side in the churchyard in simple

graves to the south-west of the church, by the churchyard

wall and only a few yards from the Strike School that

they set up.

Simon Knott, August 2018

|

|

|