| |

|

All

Saints, Crostwight I spent many happy days in the

summer of 2019 cycling around the churches between

Norwich and Cromer, and of all that part of the county I

think it is the area to the east of North Walsham that I

like best. I was visiting churches, but chasing memories

too, and when I came to Crostwight my mind was cast back

fourteen years to the time of my first visit with the

late Tom Muckley.

It was one of those balmy spring days in early April,

2005. It was getting on towards late afternoon, and Tom

and I were nearing the end of a successful day's church

exploring. Virtually every church in this area was open

every day, and those which aren't were willingly opened

by their caring churchwardens.Indeed, in years to come I

would find that even these churches were now open. There

is a real impression in this part of Norfolk of churches

held by the communities to be more than mere worship

spaces, but sacramental structures, folk museums and

touchstones down the long generations. I like them all a

lot.

We had visited everywhere we'd planned, but there was

still an hour or so of daylight left. Suddenly, off in

the fields to the left, I saw a long, low structure with

a truncated roof. I looked on the map to see that it was

the parish church of Crostwight, although there appeared

to be no village, hardly any houses even. From the map I

could see that there was an old rectory about a quarter a

mile from the church, beside the lane, but even in early

Spring it was so tree-surrounded as to be barely visible

until we actually reached it.

"Five pounds says it's locked", warned Tom,

risking his exhaust by driving up to the graveyard along

an old track. And he was right, but the key was back at

the old rectory, where the keyholder was very friendly

and welcoming. We unlocked the door, and stepped inside.

An ancient space. A wide nave, pale, rustic, full of

creamy light. A medieval screen, golden in the afternoon

shadows. And then, treasure. This is the best kind of

discovery - late in the day, unexpected, unsought. For

All Saints has one of the most extensive schemes of late

medieval wall-paintings in East Anglia.

From time to time I called in when I was cycling in the

area, but when I tipped up on a hazy summer day in 2013,

bumping my bike along the track, I found two very loud

and energetic characters in possession. They were moving

furniture, hunting for inscriptions, graffiti and the

like. They made it quite clear by their expressions and

shortness with me that they really didn't want me there,

so I wandered around for a bit until I felt I had

irritated them enough by my presence, and then I headed

on. Perhaps the experience had left a nasty taste in my

mouth, because I didn't come back for six years.

And when I did it was on one of those warm, hazy mornings

that seemed to fill the early summer of 2019, so

different to the heavy oppressive heat of the previous

year. This was my first church of the day, cycling out

from North Walsham station and reaching here about half

past eight in the morning. The church was still locked,

though this time the keyholder asked me to leave the

church open, so perhaps I was just too early. I came back

past the low, stumpy tower which was taken down as unsafe

in 1910 as part of a general restoration, the bells

rehung lower, looking up at the curious little heads I'd

remembered on the sides of the gables, and stepped

inside.

The first impression is of cool, damp stone and wood, an

organic place. But I was already looking across the

church to see again the wall paintings stretching along

the north side of the nave. The sequence probably dates

from the later part of the 14th century, perhaps the

early 15th. The scheme is essentially doctrinal in

nature, part of the enforcement of Catholic orthodoxy at

that time in the face of local superstitions, perhaps as

a response to the effects of the Black Death.

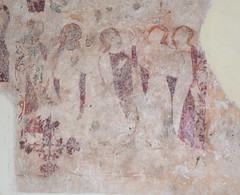

The Passion sequence of wall-paintings is the most

remarkable. It runs at three levels on the north wall of

the nave between the two windows. The arrangement is

rather complex, and several of the panels are hard to

decipher. The sequence starts in the middle level, works

towards the centre, goes up to the top level and then the

bottom level. In order, they are:

1: The entrance of Christ into Jerusalem.

2: Christ washes the feet of his disciples.

3: The Last Supper - Christ in the centre, John on the

left

4: Christ prays in the Garden of Gethsemane.

5: Christ is arraigned before Pilate.

6: Christ before Herod.

7: The crown of thorns is placed on Christ's

head.

8: The Crucifixion. Christ is crucified, a thief on each

side of him.

Below, Mary weeps, Longinus pierces his side, another

soldier offers him vinegar on a reed.

9: The Ascension of Christ.

A blank

area of wall between subjects 9 and 10 must once have

depicted the Resurrection, but this is now completely

lost. A further blank piece of wall to the east of the

Ascension image suggests a space for one more panel,

which may have been Christ sitting at the right hand of

the Father, or possibly the day of Pentecost.

There are more wall-paintings to the west of the window.

These are also fascinating. At the extreme west is a

depiction of the Seven Deadly Sins - a tree grows out of

the jaws of hell (represented by the mouth of a giant

fish) and the sins grow on it as fruit. The jaws are full

of sinners, being pushed down into hell by a devil. To

the right of this is a very curious painting. It appears

to show two women being welcomed by an angel at the gates

of Heaven, with what may be a devil low down looking on.

Pevsner thought it was a warning against gossip as at Seething, but I don't think

this can be right. Anne Marshall suggested that it is

similar to a painting at Swanbourne in Buckinghamshire,

which depicts the allegory of the penitent and unpenitent

souls. Immediately to the right of this is a much more

familiar image, St Christopher. Finally, an unidentified

Saint, a scroll above his head.

The screen

is nicely-proportioned and a gorgeous chestnut brown, but

close examination suggests that it has been substantially

restored . The carving in the spandrels in particular,

while fascinating, depicting dragons, wild men, flying

hearts and the like, does appear to be modern, at best

recut. And, curiously, while the chancel arch itself

retains extensive painted decoration, there is none on

the screen at all. Is it possible that the screen was

brought here from elsewhere as part of one of the 19th or

early 20th Century restorations?

A number

of memorials of interest survive. A brass to Henry

Lessingham, rector of Banningham who died in 1497 asks us

in Latin to pray for his soul. We are told that 18 year

old James Shepheard resign'd his breath to the will

of heaven in 1810, and equally memorable is the

inscription on the ledger stone of his grandmother, Ann

Shepheard who, dying in 1801 at the age of 65 assures us

that How lov'd, how valu'd once avails thee not, To

whom related, or by whom begot, A heap of Dust alone

remains of thee, Tis all thou art - and all the Proud

shall be.

As with

many churches around here, All Saints has an octagonal

Purbeck font reset on collonaded pillars. This one is in

very poor condition, and must have spent a long period

out of doors at some point. But its worn and fractured

sides somehow add to the atmosphere of a simple, rural

church in a tiny parish - barely 700 acres, and certainly

no more than a hundred people. It sits a quarter of a

mile from the nearest road and from the nearest house.

There is no electricity. It has, in modern eyes, no real

reason for existing any more. But it is well-kept, used

regularly, and obviously much loved.

Hubert Arthur Francis was the only man from the parish to

die in World War Two, aboard HMS Royal oak at Scapa Flow.

Today, he has a memorial as grand as any you'd find for

Lords of the Manor in other country churches. And beneath

it, his photograph in a simple frame. Still remembered.

That, for me, made it all the more special.

Simon Knott, December 2019

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

|

|

|