| |

|

All

Saints, Dickleburgh

|

|

2010 will remain memorable

for a number of reasons, one of them being that

it was the year in which, at last, I got to see

inside Dickleburgh church, at the sixth attempt.

Back in 2006 I had moaned heartily on this site

about arriving here on my bike in driving rain hoping to

shelter from in the church, or at least in the

porch in the traditional manner - one of the

functions of such structures was to provide

shelter for pilgrims and travellers. But it was

not to be. As the heavens emptied on me, I was

reduced to rattling the outer doors of the porch

in frustration, for I was kept out by a fearsome

padlock. There was no notice to tell me where

the key was - indeed, it wasn't actually possible

to read any of the notices, because they were all

locked up inside the porch. When I said as much

on this site, a kind and gentle lay reader

contacted me to tell me that Dickleburgh church

is, in fact, open all day and every day, and I

must simply have arrived too late in the day to

find it open.

|

Be that as

it may, my visits over the next few years, at differing

times of the day and in various months of the year, found

exactly the same situation, so when Peter and I learned

that Dickleburgh church was taking part in the Norfolk

Open Churches week in 2010, we headed on the first

morning at a reasonably good speed up the A12 to check it

out. You'll not be surprised to learn that we arrived to

find the church locked.

It must be

said that Peter partly blamed me. He had a point - he had

seen inside already, because on one occasion he had found

the church open, but every time he had come this way with

me it had been locked, just as when I had attempted to

see inside on my own. However, leaving Dickleburgh by a

different route we found a roadside notice advertising a

flower festival, due to begin that afternoon. So, after a

few hours we headed back, and not even fate or

circumstance could this time prevent us from finding the

porch gates open.

I'm not a

huge fan of flower festivals, but it is a useful way of

seeing inside more reclusive churches, and in any case

All Saints is such a vast barn of a building it would be

difficult for the arrangements to be a distraction.

Although considerably restored and renewed, the building

is essentially a typical 15th Century great East Anglian

church, with an earlier tower as is often the case. The

porch, which I had got to know rather well, is

spectacular, the very apotheosis of devotional

craftsmanship on the eve of the Reformation. If the tower

had been rebuilt it would no doubt have been much higher.

The kind

man on duty gave us a leaflet and told us which was the

best way to go round to see the flowers. It seemed

churlish to say that we'd actually come to see the church

rather than the flowers, especially as we were planning

to take photographs. As we wandered up the aisle he

pressed a cassette into the deck on the PA system behind

him, and soon the building was filled with the rather

unedifying sound of what appeared to be the London

Symphony Orchestra's version of A Whiter Shade of

Pale, probably from an album called something like Rock

Goes Classical: the LSO Play the Hits, or something.

I sighed, and decided that I would have to accept that my

visit to Dickleburgh church was not going to be like my

other visits elsewhere - which, as it turned out, was

quite all right, because Dickleburgh church is not like

other churches.

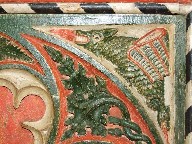

The most

famous feature is probably the screen, of which only the

dado survives, but it is intricately and beautifully

carved, and, as Pevsner observed, very unusual. Restored

sympathetically in red, green and cream, it features in

its spandrels a cavalcade of mysterious beasts and

people, of which the monk playing pipes and the dog

catching a rabbit are among the most striking.

Turning

back west, the early 19th Century gallery survived the

Victorians, possibly because it was still so new. On the

front of it there is a good set of royal arms for Charles

II dated 1662, although Mortlock thought they might be a

repainted earlier Stuart set from before the

Commonwealth. It is interesting to see a set so soon

after the Restoration of the Monarchy. Dickleburgh was

plainly a solidly royalist parish, as can be seen from

two splendid memorials up in the chancel, one to Dame

Frances Playters, who died on the eve of the Restoration

in 1659, and the other to Christopher Barnard, the

Caroline Rector of this place. Dame Frances has one of

the most memorable memorials in Norfolk - she is shown

standing in her graveclothes looking out over the chancel

for all the world as if she is surveying it from a

window, or more precisely an opera box. The inscription

below it notes that her husband William Players, deputy

lieutenant and Vice Admiral of Suffolk, a Justice of the

Peace and Colonel of the Regiment of Foot, was turned

out of all by the then rebellious Parliam't and... out of

the Hous of Parliam't whereof he had ye misfortune to be

a member.

Barnard's

inscription records an even more extraordinary story,

telling that, after he was arrested by the Puritans,

his parishioners... thought it a judgement upon them when

ye soudyers drag'd him away to carry him to Norwich

Castle; but his beloved flock follow'd him and resqued

him and hid him a long time after. it is said that

they hid his corn and threshed it secretly. You'll be

pleased to know that Barnard survived the long

Cromwellian night, and lived to see the Restoration. The

puritan arrogance and stupidity against which the good

parishioners of Dickleburgh positioned themselves has a

much quieter presence here, its only relic being a most

unusual ledger stone of the 1650s, which is scratched

poorly with an image of a lady of substance. It is a

gentle reminder of the glorification of ignorance which I

am afraid has continued to run as a minor yet

occasionally visible thread through certain sections of

English culture ever since.

| The

east window is by Hardman & Co, more usually

employed by Catholic churches, and inevitably the

work seems somewhat out of place in what is now a

thorough-going evangelical worship space.

Unfortunately, all the internal lighting was on

full, which made taking photographs of the glass

rather difficult, especially as the great east

window is most unfortunately covered with

perspex, presumably to help keep the heat in. To the

strains of the LSO struggling manfully with You

Sexy Thing or somesuch, we thanked our kind

hosts and headed out in to the churchyard. To the

west of the church is the fine school built in

1812 and extended in 1842 for the Parish, an

unusual survival. To the north of it are a number

of most interesting headstones, perhaps the most

memorable of which is to Basil Charles Lines, a

private in the 4th battalion of the Norfolk

Regiment. The deep cut relief at the top of the

headstone depicts an enlaurelled rifle and cap,

bearing the Norfolk Regiments badge. Basil Lines

lied about his age to enlist, but died of

pneumonia before he could be sent abroad. He was

just 17 years old.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, February 2011

|

|

|