| |

|

St

Edmund, Downham Market

|

|

Downham

Market's town centre is on a smaller scale than

those of nearby Swaffham, Dereham and Fakenham,

and here there is no great church lifting its

head above the market place. To find the parish

church of this interesting town, you need to head

out to the east, where it is hidden from view by

trees on top of a rise above the road to

Swaffham. Here St Edmund sits, a pretty thing in

gingerbread carstone, with an elegant

lead-covered spire crowning its squat tower. You

can see at first glance that this is by no means

a grand, urban church. I was struck by how few

gravestones survive in the churchyard. Carstone

is notoriously difficult to date, but the low

aisles and nave are essentially 15th Century I

think, while the chancel is a 19th century

rebuild. Set into the stone above the priest door

is a crucifixion scene, probably from the top of

a former churchyard cross. It all makes for an

interesting building quite unlike that of most

Norfolk towns. Although there are

exceptions, the parish churches of Norfolk's

market towns tend to be High Church in character,

even Anglo-catholic, and St Edmund is higher than

most. The interior is rather dark thanks to a

multiplicity of stained glass, but it was not

gloomy, and the smell of incense and the view of

the lighter chancel with its big six candlesticks

on the altar was evocative and atmospheric.

Essentially, this is a late 19th century

interior, but there are a couple of important

medieval survivals.

|

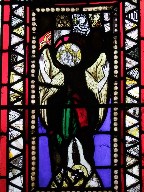

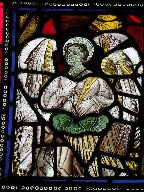

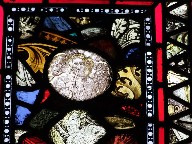

The most

significant of these is the set of 15th century glass

panels set in the west window below the ringing chamber.

They include figures from the orders of angels as well as

angel musicians, a fragment of figures rising out of the

mouth of hell from a Harrowing of Hell image, as well as

another fragment of the dead rising from their graves.

Set in

front of the tower arch is a fine 15th Century font, the

angels on the panels holding shields bearing symbols of

Saints and of the Instruments of Passion. The low west

gallery cuts off the top of the tower arch, but turning

east it creates a sense of the church opening out, and a

walk towards the chancel is from darkness into light. An

enormous glass chandelier fills the nave, while the

aisles spread into mysterious shadows beyond the arcades,

which are quite different from each other, the south

aisle being a curious mixture of arches, the north

uniform.

The east

end of the south aisle opens out beside the chancel to

form a Lady Chapel. Again, the furnishings of chancel and

this chapel reflect the Anglo-catholic enthusiasm over

the decades here, a reminder that, despite the

Evangelical reputation of the Diocese of Ely, there are

some pretty spectacular churches from the other wing of

the Church of England to be found.

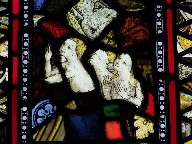

| There

is some good late 19th and early 20th century

glass, the best of which is in the south aisle.

One excellent window near to the south doorway

depicts King David accompanying musicians and a

choir on his harp. The inscription tells us that

it was placed here by the father and mother of George

William Haylock, sometime Chorister and Organist

of this Church. He died on November 9th

1918. This was just two days before the

Armistice, and I wondered if his was a tragic

death in those last few hours. But his name is

not mentioned on the Downham Market war memorial. The kind

tower captain insisted that we go up the tower

and have a look at the view, but in high summer

the trees were so full in leaf that it was

difficult to see beyond the rather empty

graveyard. It is possible to spot Ely Cathedral

once the leaves have fallen.

|

|

|

|

|

|