| |

|

St

Remigius, Dunston

|

|

The

massive Victorian pile of Dunston Hall will be

familiar to anyone who has travelled along the

main road between Norwich and Ipswich. For years

it was derelict, a brooding presence shadowed by

unmanaged woodland, but today it is a busy hotel

and conference centre, fringed by that

increasingly found blot on the rural landscape, a

golf course. There are still a few trees, of

course, and among them sits St Remigius. It is often

the case with churches in this area just to the

south of Norwich that they appear deceptively

remote, and that is certainly the case here. You

cannot reach the church through the massive gate

on the main road which leads to the hotel

grounds, which are, in any case, private.

Instead, you have to walk several hundred metres

from the back road to Stoke Holy Cross. When you

get there, the graveyard is like a little oasis,

this pretty little church in the middle. Access,

as with a number of churches around here, is

through the north door, and the stone path

outside it is slippery in wet weather, so do be

careful.

|

As I say,

the church is pretty, but doesn't really promise much

from the outside. The chancel is interesting, with its

Norman lancets, but there was a pretty overwhelming

restoration, and money does not seem to have been in

short supply here in the late 19th century. This may lead

you to think it isn't worth getting the key, which is way

off near Stoke Holy Cross, but there is much more to

Dunston than meets the eye.

From the

photograph at the top of this page, it may not be

immediately clear quite how small the building is. The

crispness of what was essentially a Victorian rebuilding

of the tower, and replacement of all the window tracery,

makes a little wedding cake of it. It was clearly

intended to be a 'view' from the Hall. But the church you

step into is by no means the urban, anonymous restoration

that you might fear or expect. Here is a delightful,

rural space, a Victorianisation on a small scale, which

has retained many good things and furnished others.

The most

spectacular survival is the 15th century rood screen,

only two bays each side of the central walkway, but

imposing in this small building. The panels have been

lost, but the lights of the upper tracery and the

spandrils are a riot of bubbly carving. Best of all are

the figures above the centre section. A wolf is paired

with a lion fighting a dragon. Above, a more imposing,

almost oriental dragon, watches as a determined wild man

creeps up on the opposite side. Wonderful stuff.

Walking

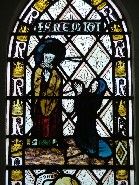

through into the tiny chancel is like stepping into a

jewel. The east window tracery is made of carved and

polished alabaster, as if this was the side chapel of a

Cathedral or great city church rather than an East

Anglian backwater. It dates from a cosiderable reordering

in the early years of the 20th century, as does the glass

on the south side, which is all good, and some of it is

medieval. This includes part of the figure of a beautiful

St Christopher carrying the Christchild through a fishy

lake, and a woman donor kneeling before St Remigius.

Possibly these were bought from elsewhere for the

restoration; the modern parts are by the King workshop of

Norwich, I think. An unlikely find is another composite

representing St Nicomedes, who I don't think I have come

across elsewhere in East Anglia.

What at first appears to be another medieval

survival is the excellent set of three figure brasses in

the sanctuary. In fact, they are later, perhaps 1630s,

and depict Clere Talbot between his two wives (not at the

same time, of course). The wives lie in their shrouds,

looking like nothing so much as if they have been

interrupted in the bath. The inscription is to the

second, Ann, and her figure brass is the best of the

three.

| A

puzzle is the pair of little openings either side

within the tower arch. Can they be, as Mortlock

suggests, partially filled in banner stave

lockers? He also draws our attention to the

elegant and oratorial ledger stone to Susan Long

in the chancel. There are other memorials from

the 18th and 19th centuries to various members of

the Long family, but walking back down the

church, you sense again that the busy life of

this place was lived in the early decades of the

20th century. Perhaps, like so many of the landed

estates of East Anglia, it was the First World

War that brought all the prosperity to an end. As the

historian AJP Taylor has observed, the Victorian

era lingered on in rural England and finally came

to a close on the Fourth of August 1914, when war

was declared. Nothing would ever be the same

again.The alabaster tracery and a hanging Art

Nouveau lamp speaks of the confidence and

elegance of the years before. The original WWI

Roll of Honour survives in a frame to remind us

of what was lost.

|

|

|

|

|

|