| |

|

All Saints, East Tuddenham

Anyone who has seen

the cover of Richard Tilbrook's lovely book Norfolk's

Churches Great and Small will remember the evocative

image of a country church seen from across a field of

poppies. The church is All Saints, East Tuddenham, and it

is a mark of the keenness of Tilbrook's eye that East

Tuddenham is actually a rather suburban place, its church

out at one end of the long, straight high street.

Tilbrook left a remarkable legacy in the form of hundreds

of photographs of Norfolk and Suffolk churches. The

Norfolk book and its Suffolk companion barely scratch the

surface, and anyone who has been to one of the

exhibitions where the large scale prints (often a metre

wide) are exhibited will know that he was probably one of

the best photographers of churches that England has seen.

However, on the dull winter's day that I first visited

East Tuddenham I fear that even Richard Tilbrook would

have struggled to make All Saints graveyard an attractive

place. The icy wind sent clouds scudding across a washed

out sky, and even the naked trees seemed to shiver. It

was a pleasure to come back on a sunny day in the spring

of 2016. The sun shone on the face of the south porch,

and the spandrels with their Annunciation scene. The

Archangel Gabriel seems to have sprung to earth in glory,

his words to her on an unfurling banner, his head as

proud and erect as the lily in his hand. Gloria Tibi

Tr(initas) it reads in crowned letters in the

flushwork across the top of the entrance between them.

The 13th Century tower rises beside a nave and chancel

that seem wholly Perpendicular, but there are no aisles

or clerestory. Did the 15th Century just add big windows

and new roofs to an already existing building? But that

can't be right, because the tower sits in the south-west

corner, so at some point the church has obviously been

extended northwards. The chancel sits in the middle of

the east wall, so it must be later than the south side of

the nave. We may surmise that the south wall is in its

original place because the main doorway on this side is

late Norman, perhaps early Early English.

On the north side of the church is the remains of an

archway that must have led into a transept. There is even

a little piscina beside it, now outside the church. It is

all a bit of a puzzle, but interesting enough for you to

make up your own idea of what happened here. You step in,

as you'd guess, that All Saints feels wide inside. The

absence of arcades means that this is a square, light

space. Bold white walls throw into relief colourful

details. The off-centre tower arch is matched across the

church by a two-light window, and the barrel-roofing of

the chancel is a counterpoint to the woodwork of the

nave.

The font is unusual for East Anglia, in that it is

circular. Vines and foliage twist around it. Pevsner

thought it late 12th Century, which means it is probably

contemporary with the doorway. Perhaps they were even

crafted by the same hands. Ahead of you there is a

startling early 20th Century triptych in the very highest

possible Anglo-Catholic taste. Christ is seated in

majesty in the middle, and three figures adore him on

each side. To the left are St Therese of Lisieux, Mother

Julian of Norwich and the Blessed Virgin Mary. On the

right are St Francis, St Felix and St John Vianney. A

curious assortment, and one you'd be unlikely to find

often in the same piece. If it seems quite out of place

at East Tuddenham, which is hardly High Church, it is

only here because it was presented as a gift. It

originally came from Norwich All Saints, one of the

Anglo-Catholic hotspots of that city, and which was

declared redundant in 1973.

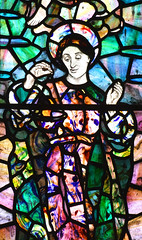

The white walls and the open spaces accentuate the colour

of the triptych, and there is another intense blast of

colour at the east end, in the form of glass by Leonard

Walker. Walker worked in an expressionist style in the

first half of the 20th Centurym and there is another of

his lovely windows nearby at Southburgh. Here, Christ as

Charity is flanked by the figures of Faith and Hope. They

move in a flowing, sinuous manner, but it is the colours

that are remarkable. It really looks as if the glass has

been tie-dyed.

There's more

interesting glass in the south side of the nave. Four

Flemish panels, two of them roundels and the other two

rectangular, depict scenes from the life and Passion of

Christ. The roundels show the Presentation in the Temple

and the Deposition from the Cross, while the two

rectangular panels are part of a much larger scene

depicting the Ascension.

Back at the west end, three curiosities. High up on the

west wall is a rare surviving Royal Arms for Charles I.

Below it, three brass figures, showing a civilian and his

two wives of about 1500. And even older, down in the

north-west corner, a knight reclines, his heart in his

hands. His feet are on a heraldic lion, and yet it seems

more lifelike than him. If you doubt the weight of his

armour, look at the pained expression on that little

lion's face.

Simon Knott, November 2020

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

|

|

|