| |

|

St Mary,

Feltwell

|

|

Feltwell

is a fen edge village on rising ground, and as

such then the size of St Mary should come as no

surprise to us. Before the 17th Century, the

undrained fen spread westwards of here towards

Peterborough, and southwards towards Ely and

Cambridge, making transport of goods and people

much easier than going by land. The Ouse headed

up towards the Wash, as it still does of course,

and until the Fens were drained it was possible

for ocean-going ships to tie up at Feltwell.

This, then, was a prosperous port, and in common

with many other fen edge villages it has a church

to match. In fact, it has two churches, as there

is also St Nicholas, a pretty little thing about

half a mile off, and now in the care of the

Churches Conservation Trust. But if you were to

come to Feltwell for the first time, the

structures that would strike you as most

remarkable would probably not include the

churches. Three large communications domes rise

from RAF Feltwell, now part of the United States

Air Force's East Anglian operation. They look

like nothing so much as giant golf balls, and are

visible for miles. |

St Mary

seems tightly shoehorned into its long, narrow

churchyard, an effect accentuated by the wide north aisle

added by enthusiastic Victorians. The view from the south

is almost urban in its appearance, without the luxury of

a wide and ambling graveyard, and emphasises the sheer

size of the building. But the grandest touch of all is

south-west Norfolk's best tower. The sumptuous parapet

and pinnacles date right from the eve of the Reformation,

as probably does much of the nave, for a money-raising

campain of 1494 was used for a massive reconstruction

after a fire. The chancel is earlier, probably 14th

Century, and overall the effect of aisles and clerestory

beneath the great tower is a happy one.

The church

is open every day, and you step inside to a wide, open

interior, the smell of old wood and fresh-cut flowers,the

sight of dust falling silently in summer sunlight. The

benches to the west are almost entirely medieval, and if

the fire mentioned in 1494 affected the nave then they

are probably early 16th Century. The bench ends are

mostly vandalised, but the best represent the Works of

Mercy, including Feed the Hungry, Welcome the Stranger,

Bury the Dead and Visit the Prisoner.

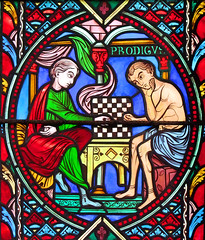

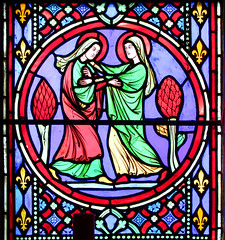

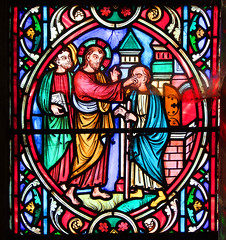

Beyond the

rood screen, the chancel beckons, glowing and jewel-like.

You step through to find East Anglia's largest expanse of

19th Century French cathedral glass, both here and in the

19th Century south aisle which extends up to the east

wall of the chancel. It is by the Didron and Oudinot

workshops of Paris, and was installed in several

campaigns between 1859 and 1863. You wouldn't want every

church to have had this visited upon them, but here it is

magnificent. I like the Didron window telling the story

of the Prodigal Son best.

The size

of the chancel is accentuated by those great walls of

glass, and the floral altar frontal complements them

perfectly, although it must be said that the near-life

size figures of the Holy Family stepping down the chancel

steps are a little bizarre.

Stepping

out of the chancel again, you see there is a two-light

window beneath the tower by Didron depicting the story of

Adam and Eve. This is interesting, because the rest of

the glass in the nave is clear, but the French glass in

the chancel begins at the opening of the New Testament

and then heads east. Was there a plan to fill the nave

windows with Cathedral glass as well, telling the story

of the Old Testament? I'm glad they didn't, though it

would have been interesting to see.

| I

went into the wide open space of the 19th Century

north aisle, bigger than many churches on its

own. The architect was Frederick Preedy, who did

lots of work in this part of East Anglia, and it

was completed as part of the same scheme as the

glass, in 1863. Pevsner gives the cost of the

aisle as £1,500, about £300,000 in today's

money, which seems about right given that labour

was cheaper. The east end of the aisle

forms a war memorial chapel, and the rest is

given over to a kitchen and tables and chairs, a

sensible arrangement - a lovely medieval church,

with 21st Century amenities attached! But for all

the medieval glories of Feltwell, and for all its

21st Century life, it is the 19th Century which

shaped it and which leaves upon it its lasting

impression. As if to ensure this, memorials to

19th Century worthies punctuate the walls,

including that to Edward George Hibbert, late

Lieutenant Colonel of the Grenadier Guards.

Hibbert died in 1901,after having served

throughout the Crimean Campaign with the 50th

(Queen's Own) Regiment, and was present at the

Battles of Alma and Inkerman and the Siege and

Fall of Sevastapol.

|

|

|

|

|

|