| |

|

All

Saints, Hilgay

|

|

Hilgay

is one of those large, independent south-west

Norfolk fen villages that feel as if they really

ought to be in Cambridgeshire. The church is set

away from the village centre, and you'd be

unlikely to find it without a map if it wasn't

for the handily named Church Street. All Saints

is set about a hundred metres back from the road,

and the avenue of limes that lead up to it are

undoubtedly the longest in East Anglia. A local

once told me it was the longest lime avenue in

the world, which may also be true, although I

don't suppose there are hundreds of lime avenues

in Africa, Latin America and South-East Asia

queuing up to compete with it.

The church appears long and apparently low,

although this is in fact an illusion caused by

the squatness of the tower. It appears very

un-East Anglian, the nave and chancel in layered

carstone and the tower in white brick. The

carstone of the south aisle is not layered but

ragged, and this creates a very primitive, rugged

effect, like a marbled gingerbread cake. The

ramshackle appearance of the tower contributes a

bit as well. |

The large

gravestone with an anchor, cross and heart on this side

of the graveyard is striking, and you might think at

first it is the memorial to Hilgay's most famous son,

Captain Thomas Manby. Manby was the inventor of the Manby

cradle, a device for rescuing sailors from stranded ships

at sea (I hope you're taking notes, there will be a test

at the end) but in fact it isn't. His memorial is inside

the church. When I came here in 2005, this large

memorial, which actually depicts the Christian virtues of

Faith, Hope and Charity, still had a heart-shaped

lead-plate with the name and details of the grave's

inhabitant, but it won't surprise you to learn that this

has long since been stripped away. The best memorial on

this side of the church is to John Whittowe, who died in

1891. It features a deeply cut relief of a windmill, the

workers busy unloading sacks of grain from the back of a

cart.

George Street undertook the considerable restoration of

All Saints in the 1860s, although the tower predates this

by about seventy years, replacing one which collapsed in

the 1790s. The interior is wide and open, and at first

appears almost entirely 19th century. The aisle is as

wide as the nave, and the aisle chapel altar is as grand

and dressed as the main altar. It feels a little like two

churches side by side. Just inside the door is a very

rare beast, a glass-walled funeral bier. The font is a

grand Victorian marble job, and matches the not quite so

successful pulpit. They do seem a little out of place

here, a reminder that Street's urban, sophisiticated

style is sometimes a little uncomfortable in East Anglia.

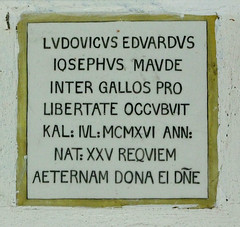

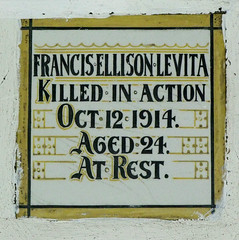

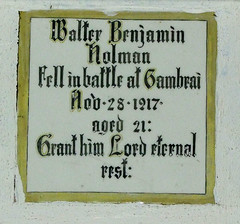

A fashion

which never really caught on, more's the pity, was the

practice of placing encaustic memorial tiles on the wall.

This seems to have arisen in the 1880s, and had more or

less disppeared by the 1920s. There are some at Hilgay,

which are particularly interesting because they include

three to boys killed in the trenches of the First World

War. One of them is in Latin: Ludovicus Eduardus

Iosephus Maude, it reads, inter gallos pro

occubuit kal: Iul:MCMXCI ann: nat: XXV Requiem aeternam

dona ei Domine. This translates as 'Louis Edward

Joseph Maude, who died in the war for freedom, first day

of July 1916 aged 25. Grant him eternal rest Lord.' Which

is to say, of course, that young Louis Maude died on the

first day of the Battle of the Somme.

There is a

good set of 15th century benches with animals on some of

the ends, including a rather disturbing anthropomorphic

creature that I suppose must be something from a

bestiary. From a century or so later comes the memorial

to Henry and Ursula Hawe in the south aisle chapel.

All Saints is at first sight not the most exciting of

churches, but it is full of little details and has a

lovely harmonious feel, from the stations of the cross to

the good late 19th century glass by Ward and Hughes, from

the screen brought from the redundant St Mary Beswick in

Manchester to the jaunty little gallery shoehorned under

the tower which Pevsner, unaccountably, thought dull.

Captain

Danby's memorial is in the south aisle chapel,

and records that his is a name to be remembered

as long as there is a stranded ship. Poignantly,

the memorial also remembers four of his eight

brothers and sisters who died in infancy. It is a

fairly typical sentimental memorial of the

mid-19th century, but has a striking addition

that you only notice after a moment. In another

hand along the bottom, someone has inscribed

carefully The public should have paid this

tribute. How curious! There must be a story

there somewhere.

This church has a long-standing Anglo-catholic

tradition, and as part of that it used to be open

every day. I am afraid that this is no longer the

case, and there is not even a keyholder notice

now. |

|

|

|

|

|