| |

|

St

Michael, Hockering

|

|

It

had been the wettest winter in a generation, and

2016 ushered in an unremitting procession of

gloomy, damp weekends. But at last in April there

was a stirring of sunshine as Mother Nature began

to get her finger out, and at last I was able to

return to Norfolk to visit some churches. One of

them was Hockering. I had long looked forward to

coming back here, not least because ten years

previously it had provided me with one of the

more memorable experiences of my journey around

the churches of East Anglia. I returned to the

pleasure of a church stunningly cared for, after

many years of decay. I had witnessed the start of

this TLC some ten years before, when I'd had the

privilege of meeting one of the truly great

Norfolk eccentrics. But sadly, I came back to

discover that he is no longer with us. Back in

2006, I had written: we came to Hockering the

morning after the second exorcism. I couldn't

honestly say that all was calm. It was a day of

sunshine and blizzards, when the light first

dazzled and then submitted to a baffling of

snowflakes as fat as goose feathers. We

church-hopped between the flurries, catching

glimpses and seeking shelter. It was a day to

battle with obscurity, and as I said to Peter

later, it was difficult to know where to start.

|

First of

all, perhaps, there was the screaming skull. Or was it

the cold spots? There were a lot of cold spots,

apparently. But none of that could have happened without

the phone call about the SatNav. And then later there

were the Saints, and there were the extraordinary

Berneys, and there was Catholic treasure from beyond the

great divide. Such a lot to remember. Perhaps it's best

to start at the beginning.

St

Michael, Hockering, is a small-scale work of the early

14th century, vigorously enhanced in the late 15th or

early 16th century, and then, in part, enthusiastically

refurbished by the Victorians in the 1850s, as we shall

see. However, it still retains a lot of its decorated

charm, and the tower is curious because the buttresses

stop short of the later bell stage, making it look like a

small head on broad shoulders. The pretty pinnacles and

battlements help to alleviate this; a crowning, if you

like. The church sits among fields to the west of the

village, and just to the north of the main road from

Norwich to the Midlands, which slices clinically through

the otherwise profoundly rural landscape of central

Norfolk.

We were in Peter's car, heading

across the A47 to St Michael. The keyholder was in the

back. He was in his fifties I suppose, a cheerful man

and, as it would turn out, a kindly man. He was heavily

bearded, with longish hair, as if he had intended to be

on the hippy trail to India, but had ended up in Norfolk

instead. He wore a leather jerkin, rubber waders and a

pearl earring. We were really

grateful that he was giving up his time. He told us about

the lot who'd come yesterday. They'd also been grateful.

They hadn't known, of course, that if they'd waited a

while he'd have been there anyway. He spent hours every

day at the church, because he was verger and sexton and

handyman and cleaner and silver polisher and carpenter

and chief cook and bottlewasher all in one. We hadn't

known that either of course, but it didn't matter.

Yes, that lot yesterday had been

waiting for him when he got there, and he knew straight

away it was an exorcism because there'd been an exorcism

five years ago, and this was just like that. And five

years ago funny things had been happening; you'd take the

candle stocks off the altar and lock them away, and when

you were back out in the nave you'd hear a clatter, and

you'd go back to the vestry and find them rolling around

on the floor. But now they had this woman with them who

could sense evil. She could see it, she could smell

it.

I was trying very hard not to catch

Peter's eye. I feared it might break the spell. I have

now visited nearly 1200 churches in Norfolk and Suffolk,

but this was gold dust. I had never heard anything like

this before. My mind rolled, and I felt a thrill of

excitement.

Fifteen

minutes earlier, when we'd first arrived at the church,

I'd actually been feeling a little low. We'd just been

subjected to the flat-lining pulse of Honingham St

Andrew, and so to find another locked church was

depressing, even though it had a keyholder notice.

Through the magic of the OS street atlas of Norfolk we

found the house where the keyholder lived; but when I

knocked on the door, there was no answer. I waited and

waited while Peter turned the car around. The house

wasn't far from the church, but it was on the

far side of the A47, which no pedestrian crosses safely.

And I waited, and I thought to myself, I wonder if

there's a key hanging up somewhere? Because some

keyholders keep the key hanging up outside for other

parishioners to use. And just as I thought I might look

for it, the door opened.

Within

moments, I knew that I was in the presence of one of

Norfolk's great eccentrics, which is saying something,

because in this day and age the county may well have

cornered the market, at least as far as England goes. And before we left Hockering, which would be

fully two hours in the future, I would know that, thanks

to this friendly, candid man, if any church in Norfolk is

to survive the next quarter of a century it will be

Hockering.

He invited

us in to his house while he looked for the key, but what

had surprised him was that we had found his house at all.

Because that lot yesterday had phoned him up and said

they couldn't find his street, and asked him for the post

code of the church so they could put it in the SatNav,

and then they could let the SatNav direct their car to

the church, and he laughed and said there was no need,

he'd meet them there, and the church was easy to find

because it was the big thing that looked like a church.

He'd got to the church, and they

were waiting. Three clergyman and a woman who saw things

other people couldn't see, felt things they couldn't

feel. And she'd wandered around, poking in corners, and

she found all these cold spots. There'd been one in the

porch, and one by the font, and several in the vestry.

Worst of all, up in the west gallery she'd sensed a

screaming skull. That was the motherlode as far as evil

was concerned, and the exorcism team sprang into action.

I made up my mind that, more than

anything, I wanted to go up into the west gallery and

sense the screaming skull. We got to the churchyard, but

the porch was out of commission and cordoned off. It

wasn't clear if this was due to falling masonry or

demonic possession*. Instead, we were let into the chancel,

through the Priest's door.

| |

|

Hockering chancel is an

opulent 19th century refurbishment quite out of

character with the rest of the church. The

chancel arch and its matching stone reredos in

particular are textbook examples of the

international mid-19th century Early English

style, familiar to church explorers from

Vancouver to Calcutta and beyond. The arch in

particular must have cost a fortune. Fortunately,

the Victorians used the old bench ends for the

stalls, or perhaps they had simply run out of

money by then. Certainly, the 1890s rood screen

does not match the stonework for quality. However, west of the chancel arch is

a small nave with a north aisle, and it is full

of local character, with an air of the centuries

conspiring, through a mixture of care and

neglect, to leave us something unique. And best

of all is Hockering's wonderful font. It sits

beneath the George III royal arms on the front of

the west gallery, and it soon distracted me from

searching for skulls. The bowl is Victorian and

perfunctory; the shaft is medieval, and

wonderful.

|

It depicts

eight Saints, standing in niches. Their heads were

whacked off by 16th century protestants, and have since

been replaced, but they are in the main in good

condition, beautifully clear and identifiable. They

include St Michael, St Andrew, St Margaret, St Catherine,

St Christopher and the Blessed Virgin and child.

It has to

be said that the interior of St Michael is slightly

ramshackle, though pleasantly so**. It is, however,

very clean. This is because the keyholder has been

systematically working his way through the building,

cleaning and sealing dusty surfaces, polishing the wood

and scraping the muck off the stone. So far, it has taken

him almost two years of daily work, and he still isn't

quite finished. Now, England is full of people who love

their parish church, but it is rare to meet someone who

so wholeheartedly backs up this love with the sheer sweat

of his brow, and I admired what he was doing here

immensely.

The

majority of the benches in the nave are late medieval,

with simple, carved poppyheads. At the front, a box pew

bears the arms of the Berney family, who are one of the

long-established stars in the firmament of Norfolk

landowners. By the 13th and 14th centuries they were busy

organising the peasantry in these parts, as well as

elsewhere in Norfolk. Incredibly, they still live at

Hockering Hall, the current incarnation of which is a

modernist building of the 1950s.

And St

Michael, which is by no means one of Norfolk's more

significant churches, is still their church, and

their patronage still falls heavily here. The current

family attend the church every Sunday, and they form a

significant proportion of the tiny congregation. I

thought that this was wonderful, like something out of an

Evelyn Waugh novel. Apparently, it is still the job of

the churchwarden to make sure that nobody else sits in

the Berney pew. A few months back, someone they hadn't

seen before arrived early for the evening service, and

sat down in it. There was a collective sharp intake of

breath from the half dozen or so locals sitting behind,

and the stranger had to be turfed out and rehoused in the

cheaper seats.

Mortlock,

visiting in the early 1980s, said that there was an air

here of a church not being forgotten, but not cherished

either. He'd probably say the same today, but I think

this is simply because of the junkshop atmosphere of a

quirky church with much of interest and more than a

little rustic character**.

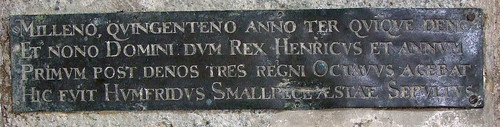

Typical of

the quirkiness is the brass to Humphrey Smallpece,it

reads Milleno, Quingenteno Anno ter quique deno et

nono Domini, dum Rex Henricus et annum primum post deno

tres regni Octavus agebat, Hic evit Humpfridus Smallpece

aestate sepultus.

This

translates as 'In the summer of the year 1539, as King

Henry VIII began the 31st year of his reign, Humphrey

Smallpece died, and was buried here'. This is curious,

because it means that here we have an inscription from

the very earliest stages of the English Reformation, when

England was still a Catholic country, and yet it is

entirely secular.

At last,

we went up into the gallery. It has been built into the

splay of the west window, and is approached via the tower

stairs, but it is too rickety to be used by the public

anymore***. It is cluttered

with equipment - a lawnmower, planters, and old books

under a carpet of dust. No screaming skulls, though. The

keyholder could see in our faces that we thought it

untidy, and he laughed. "This is what the rest of

the church used to be like", he observed.

Finally,

something genuinely extraordinary. Hockering parish

possesses some 16th century plate, including an exquisite

silver paten with the head of Christ in the centre. This

can be dated accurately from a will bequest of 1520.

There is also a cup of 1570, post-Reformation of course,

bearing the inscription HOKRYNG TOWN. These are now kept

in safe storage in Norwich, not at the church, but they

had recently been returned to the parish from an

exhibition, and were due to go back to Norwich later that

afternoon. Our friendly keyholder produced them with a

flourish for us to look at and photograph - tremendous

treasures from a world ago, now rarely exposed to the

light of day.

So, that

was Hockering. We took the kindly keyholder home, and

headed on to the relative sanity of the Wensum group of

parishes to the north. As we drove, I was thinking about

the Berney pew, Noel Coward's chorus running through my

head:

The

Stately Church of England, how beautiful it stands,

To prove the upper classes have still the upper hand

and

wondered to myself if, when I came to write about

Hockering, I should mention the exorcists. The thing is,

I get an increasing number of crank e-mails from people

claiming to represent organisations with wacky names like

the Suffolk Paranormal Society, and the North Essex Ghost

Hunters. They ask me if I know of any haunted churches

for them to investigate. My answer, in the days when I

still bothered to answer them, was no, of course I don't.

How on earth could a functioning, welcoming, prayerful

church possibly be haunted? I fear they may now and try

and get their talons into Hockering, and it will be

partly my fault. All I can say is that there are now no

ghosts at Hockering, and I don't believe that there ever

were.

* The

porch has since been beautifully restored.

** This is no longer the case, the church is immaculate

inside.

*** The gallery is no longer accessible.

Simon Knott, March 2006, revised and

updated May 2016

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site

|

|

|