| |

|

St Peter,

Hockwold

|

|

Hockwold

merges into Wilton in this corner of the

Brecklands. We are close to the Suffolk border

here, and not so very far away from the

Cambridgeshire border. We are also not so very

far from the fen edge, so stone was a possibility

in the late medieval period. They used to bring

it by barge across the undrained fen from the

quarries beyond Peterborough. But what would be

the point? For we are at the centre of the

medieval flint industry. Lakenheath

railway station, on the Norwich to Cambridge

line, sits just to the south of the village, but

unfortunately it now only operates a

'parliamentary service' of two trains a week.

Wilton's church now serves both villages in the

joint parish, and St Peter is in the care of the

Churches Conservation Trust. It is open daily,

although it wasn't on the occasion of my first

visit, a day of heavy rain in the Autumn of 2009.

I pottered about the dripping graveyard with its

pleasing array of late 18th and 19th Century

headstones, and knew I would have to come back

soon.

Seven

years passed, but in the hot summer of 2016 I

came back to Hockwold. It was a day of rising

heat, the precursor to the hottest days of the

year which were to immediately follow. And this

time, the church was open. At first sight, St

Peter is slightly odd, because although this is a

big late medieval church with a south aisle and a

clerestory, the older tower is offset at the west

end of the aisle. This, then, was the site of the

original church.

|

But there

is more to it than this, for, as Pevsner notes, there was

a bequest as late as 1533 for 'hallowing' the church.

This date seems to fit the wonderful angel roof, which is

spectacularly late - another 14 years, and such imagery

would be quite illegal. Is it coincidence that the angels

are already morphing into more secular figures?

There is

no north aisle or clerestory, but the great windows of

the north side fill the church with light. Above the

north door is a patchwork of late-medieval painted

patternwork.

| Stepping

into the chancel, the east window is filled with

Clayton & Bell's glass depicting the

Crucifixion, flanked by the Resurrection and the

Ascension. Below, Christ enters Jerusalem, prays

at Gethsemane and carries his cross. Well, I

don't know. Does it really enhance this place? I

don't think I've ever seen a Clayton & Bell

window to set the pulses racing, have you? In

their early days they could be good -

witness the excellent work at East Winch, not so

very far from here. But you feel that sometimes a

spiritual space cries out for more than a mere

safe pair of hands. And I am

afraid that both Pevsner and Mortlock moaned

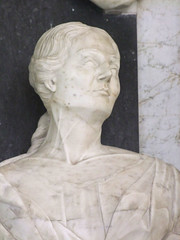

about the memorials that flank it. To the right,

sober and serious busts of 1719 to John and Maria

Hungerford sit awkwardly, shouldering for space

in the frame. There are musical instruments above

them. To the left, an unconvincing cherub for

Cyril Wyche of 1780 holding a wreath, having

leant his upturned torch against the wall. Me, I

can take or leave 18th Century memorials, but

they matter to Pevsner and Mortlock.

Both try to be kind. Neither of the monuments

has the mark of quality, though they do try, argues

Mortlock. Badly carved, which is unlike

Singleton (the carver) says Pevsner.

Mortlock decides that Cyril Wyche's cherub is sadly

overweight.

Oh

dear! Best turn back to the nave, and that

utterly wonderful roof.

|

|

|

|

|

|