| |

|

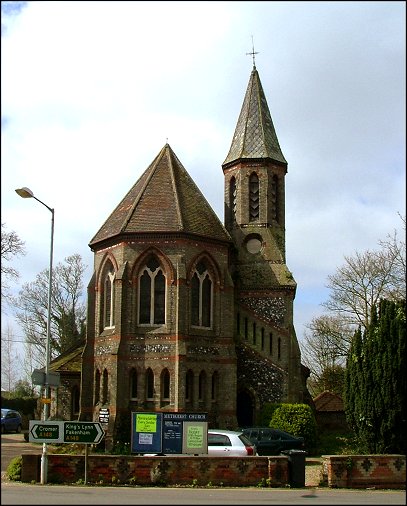

Methodist

church, Holt This terrific High Victorian building sits

at the busy junction in the middle of Holt where all

roads meet. The medieval Anglian parish church of St

Andrew is way down beyond the market place, and not

visible from most of the town, so it is by the Methodist

church that those passing through will remember Holt.

It might

easily be mistaken for an Anglican church, or a Catholic

one. The 1860s work of Thomas Jekyll, this long tall

church hides behind its octagonal apse, a turreted spire

rising to the north. The building is in polychromatic

banded brick, with flint for details, and there are fine

grotesques forming headstops to the window arches. A long

clerestory runs the length of the church on both sides.

It must have cost an absolute fortune, and was the gift

of William Cozens-Hardy of Letheringsett Hall. Shortly

after he died, the family converted to Anglicanism.

| As

ornate as the exterior is, it cannot match the

extraordinarily detailed interior, a riot of

gorgeous coloured brick, cast iron columns and

tracery in the Early English style.

Unfortunately, almost none of this can be seen by

the public today, because the interior has been

partitioned off to such an extent that it is as

if you are entering a shoe-box set inside a

wedding cake. The western third of the interior

has been walled to form meeting rooms, and the

organ loft in the upper half of the apse has been

glazed. The lower half of the apse is a vestry

behind a screen which backs the preaching

platform. Most overwhelming of all is

the low ceiling that slices the church just at

the level of the arcade arches. This was

installed because of the fabulous cost of heating

this building. Unfortunately, Jekyll's

architecture was designed to lift the eye, to

give an impression of a towering space, and your

gaze today is blanked by an acreage of

polystyrene tiles. It makes perfect economic

sense, but ultimately defeats the vision of the

design.

|

|

|

There is

one crucial survival to balance this, however. Holt

Methodist church retains in full its original

furnishings, a range of pretty box pews that interlink

across the nave, two passageways in the aisles connecting

the west end with the east. The interior is beautifully

cared for, but the furnishings ache to be flooded with

light - it was never meant to be this dark in here.

The people

here were very friendly, and one kind man even took me

behind the scenes. We stepped into the vestry behind the

platform, and climbed into the upper part of the apse.

This is the former organ loft, and from here there is the

surreal sight of the top side of the ceiling, suspended

by wires from the roof high above; the lid of the

shoe-box, if you like. He told me that it does

keep the heat in, but ironically the congregation is now

so tiny they can't afford to run the heating anyway - and

the heating is now in need of replacing, an impossible

dream. In this sense, the building has no future, a

curious thing to ponder as I stood at the top of it.

There is

more of the church above the ceiling than below it. Up

here, you can see the details that are no longer visible

to the public - the gorgeously-banded chancel arch, the

elaborate curly-leafed capitals and the strong lines of

the clerestories, Most dramatic of all is the massive

rose window, far away at the west end. Its clear glass

has flooded with light nothing but the tops of hundreds

of polystyrene tiles for more than twenty years now.

Simon Knott, May 2006

|

|

|