| |

|

St

Andrew, Honingham I had almost given up hope of seeing inside

Honingham church, until my friend John told me he'd

arranged for it to be open, and would I like to come

along? In truth, I was wary about meeting a character I

had encountered at the church some ten years previously;

not so much for what had happened, but that I had written

about it in some detail afterwards. I was a little

apprehensive, therefore, to turn up and discover that the

man opening the church was the same one I had met all

those years before. But it didn't matter, because he

didn't remember me, and probably had never read what I

had written.

|

|

And

I found I liked Honingham church rather more than

I had expected to. There is a rich atmosphere of

the last decade of the 19th Century and the first

decade of the 20th, and the Victorian glass is

really very good. It can't have much of a

congregation, and I decided that it was

essentially a churchwarden's hobby church, a

fiefdom. He obviously did everything here, kept

in in good order looking spick and span and

shipshape, and locked it determinedly against

anyone who wanted to see inside without attending

a service. I imagined that even God

would have to wipe his feet and mumble

apologetically if he wanted to get inside. All

well and good for now, but once the churchwarden

has gone it will soon be lost to us.

In

2006, I had written: This big, locked,

Perpendicular building, the nave and chancel

rebuilt by the Victorians, is surrounded by a

wide graveyard. On the north side there are

sparsely scattered headstones, but to the south

the church is set within a wide murderous curve

of the A47. To describe this church as a landmark

on the road is to assume that it would be safe to

look up from the wheel to spot it; the stretch of

the road between here and Hockering has claimed

more deaths than any other since the A47 was

taken outside the villages. I'm not suggesting

that the church is responsible for this, of

course, just that spotting it shouldn't be one of

your priorities.

|

If a

Martian came down and landed in the graveyard of St

Andrew, Honingham, what on earth he would make of it?

Would he think it was an art object? A barn, or storage

facility? Or would he search for an industrial purpose?

Perhaps the tall pinnacles on the tower might suggest to

him that he was at the site of a scientific experiment.

If the

Martian had any brains, and I assume that he would have

if he'd made it this far, he might perceive that the road

is a lot newer than the church, and perhaps he would

decide that the church was a relic of the past, its

function now sidelined, perhaps forgotten altogether.

Indeed, he might wonder if the road had been built

deliberately to speed humans past this building and the

tall stones set around it.

Perhaps

this was a dangerous place. Or, maybe, it was simply an

embarassing reminder of past superstitions, a haunted

site. An unlucky place, perhaps. The Martian might watch

the traffic hurtling past, the drivers deliberately not

looking, and think yes, that must be right. Whatever he

decided, it would have to be based on a survey of the

exterior, because St Andrew is always locked,

unless the Sunday club is in session. He wouldn't even be

able to look through the windows, because they are filled

with frosted quarries.

Eventually, he might find the porch, and

think it is some sort of antechamber (not an entrance, of

course, for the doors beyond are locked) and for a moment

ponder the holy water stoup, now filled with an old birds

nest. What on earth would he make, I wonder, of the

signboard on the wall that reads in part:

Friend, you have come to this church.

Leave it not without a prayer.

No one entering a house ignores him who dwells in it.

This is the house of God, and He is here.

Pray, then, to him who loves you, and bids you welcome,

and awaits your greeting.

A lovely sentiment, no doubt; but the

Martian would still be left locked out of the house of

God - if it is the house of God, of course, for

if the locks and chains keep out the stranger and the

pilgrim, how on earth can it be that God is in there to

bid us welcome?

My friend Peter has been trying to see

inside this church for years. We came this way most

recently in early March, 2006. The day had started in

bright sun, but as we headed here from Marlingford the

east wind blew sheets of glacial cloud above us, which

turned grey and, as we parked the car, turned to snow.

Parking is difficult; there is a layby, but you need to

approach from the west to park here. Otherwise, there is

a drive which goes up to the east end of the church, but

this was already occupied by a large BMW estate. We

parked in the layby, and sat in the car for a moment,

watching the fat flakes thicken.

What to do? We decided that we might just as

well get out and go and take a look. Either, by some

miracle, the church would be open and offer us shelter,

or we could confirm our prejudices about the perpetual

locking of St Andrew and be on our way.

The south side of the church has been

cleared of headstones, and they have been placed in two

perfectly straight lines, about 15 m apart. What would

the Martian make of this? Some sort of sports arena,

perhaps? Or a place to worship the sun at the solstice?

Our Martian couldn't possibly be expected to

know about the great lawnmower enthusiasm of the 1960s

and 1970s, when so many graveyards were cleared like this

one. But the dead have their revenge, and this wide open

space is now scattered with an acne of molehills.

We got into the porch and tried the inner

door, which was locked of course; although it did feel as

though one great shove with a shoulder would probably

open it. And that was when the heavens opened. The snow

was so thick in the air we could only just make out the

suicidal cars thrashing up the main road to and from the

Midlands. Peter is a careful driver, and he didn't much

fancy heading on in a blizzard, and there didn't seem

much point getting caked in snow just to go back and sit

in the car, so we sheltered from the weather in the

porch, and read the notices miserably.

I noticed that the presentation to the

living had been suspended, which sounds drastic but

simply means that the parish can't afford a Rector. The

annual accounts were posted, and I noticed that the total

income for the year was roughly the same as the weekly

income of the church I attend in the middle of Ipswich,

so this is a small parish. Eventually, I exhausted the

possibilities of the noticeboard, and, feeling that I had

probably squeezed the last ounce of pleasure out of the

porch, I gazed out at the graveyard. This was when I

noticed something rather curious. The back of the BMW

estate was open, and beyond the second line of

gravestones a smartly dressed man was standing in the

snow bashing molehills with a spade.

At first I thought this must be an act of

devotion on the part of a parishioner, or simply a

Saturday morning habit. And then I wondered if it might

be some kind of country lore: if in the snow you

clear his stack, mister mole will not be back -

perhaps this man had been waiting for it to snow for months.

We watched him for a while, the snow

blanketing the sound of his spade into silence, rendering

it surreal. But the wind was vicious, and so we stepped

back into the porch, and worked out where we wanted to go

next. It was while we were pondering over the map that we

heard footsteps, and looking up saw that the smartly

dressed man had approached us. He looked at us

quizzically.

"Just here out of interest?" he

asked.

"Well, we'd like to be", I

replied, indicating the door. "But the church is

locked."

This was such a heavy hint that, once

dropped, it hit the floor with a loud clang.

Surely, if this man had a key, he'd give it to us, or let

us in. But he just smiled sadly and nodded in agreement,

as if to say yes, the church was locked, and

there was nothing he could do about it. Perhaps he'd been

trying to see inside for years as well. Instead, the

three of us exchanged a few polite comments about the

weather, and he wandered off back to his moles.

And then ten years passed, and here I was

again at Honingham church. No moles now, and so the

churchwarden was at leisure to let us in through the

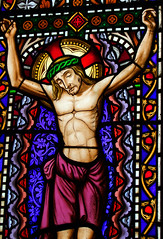

chancel door. The first impression was of the jewel-like

intensity of the chancel windows, several the work of

George William Taylor soon after he had taken over the

O'Connor workshop in Berner Street, London in 1877.

Indeed, the windows are actually signed Taylor late

O'Connor. I always find Taylor's manga-eyed women a bit

mawkish, but in these early days he was probably working

with the O'Connor pattern book, and the combination of

their cartoons and his romanticism is very pleasing, even

if there is a bit of manga creeping in. But in the end,

Taylor was unable to revive the O'Connor's fortunes. The mass-produced glass of the workshop was

becoming unfashionable with the rise of the Arts &

Crafts movement, and they weren't able to compete with

the economies of scale of the really big workshops like

Hardman & Co and Ward & Hughes. They produced

their last glass in about 1900 and the company closed

soon afterwards. The main subjects here are all concerned

with bringing the dead back to life: Peter raising

Dorcas, Christ raising Jairus's daughter, and so on. Best

of all is a triple window of Nativity, Crucifixion and

Resurrection, probably produced by the O'Connors before

George Taylor came along.

By contrast with the

chancel, the nave is startlingly plain, perhaps a result

of a considerable restoration in the early 20th Century.

The memorials are all gathered at the east end and

include one to Sir Eric Teichman. After a distinguished

career in the diplomatic service, mainly in China,

Teichman devoted his life to raising funds for Dr

Barnardos Homes. He lived at Honingham Hall, and in the

winter of 1944 he was shot dead in the grounds by two

American servicemen who were poaching there. The soldier

who fired the fatal shot with an M1 Carbine, a Private

George E Smith of Pittsburg, USA, was sentenced to death

and hung at Shepton Mallet prison on VE Day, despite a

call for clemency from Teichman's widow. Of course, the

memorial gives you none of these details, but the

incident was quite a cause celebré at the time,

I believe.

So it was all very

interesting, and despite the gloom of the nave I decided

that I liked Honingham church. We went out to the car and

set off for East Tuddenham.

But back

in 2006 we were still sitting in the porch, of course.

The snow gradually thinned, and at last it stopped. We

stepped out, examining the sky for signs. An uneasy truce

had set in. Just a thin dusting remained on the grass to

show that it had ever snowed; the sun was edging to come

out, the white rime on the green fading, but there were

more sheets of greying clouds huddled off in the

distance. It was time to go. We wanted to make a

statement of some kind, and so we left the porch gates

open, as if to suggest that the the doors were not

barred, and that God was in His dwelling house

waiting to bid a welcome.

But by the

time we got back to the car and headed eastwards past the

church, someone had already closed them.

Simon Knott, March 2006, revised and

updated May 2016

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site

|

|

|