| |

|

St Peter,

Ketteringham Ketteringham is

just south of the main A11 road, but clever planning

policies make it seem remote. More remote than it felt

before the road was built, probably. The village

straggles along a mile or so of street, and the church is

about half a mile to the south. My OS map showed a road

leading up to it, but when we looked for this road it

turned out to be the private drive of Ketteringham Hall,

and was locked off. Instead, we had to go out into the

country on the road to East Carleton and then come back

northwards towards the church, which sits immediately

beside another entrance to the Hall grounds. You can see

at once that this was a park church, with the main

churchyard entrance pointing towards gates from the

grounds, the public lychgate in the corner added almost

as an afterthought.

Another sign that this was a park church is that it was

patently given a good going over in the late 18th

century. The antiquarian-minded squirearchy of the times

didn't know much about medieval architecture, but they

knew what they liked. Hence, the fortress-like pinnacle

to the tower stairway, and the guardian angels at the

other three corners. The residents of the Hall at the

time were the Atkyns, and their successors were the

Boileaus, whose famous mausoleum is to the east of the

church. This was built under traumatic circumstances, one

of the central incidents in Owen Chadwick's masterly book

Victorian Miniature.

The mausoleum, a blockish thing in a kind of Egyptian

Doric style, was covered in tarpaulin when I first

visited in 2005, and I later discovered that it was on

Norfolk's 'Buildings at risk' register. The Boileaus no

longer live at Ketteringham (they left in 1947, as a

consequence of two hefty lots of death duty) and the

family apparently no longer feel a commitment to maintain

it. There was a request by them in 1991 for it to be

demolished, but the mausoleum is now a listed building,

and this did not happen. In the end, it was taken on by

the Mausoleum and Monuments Trust and restored to a good

state.

For many years after the Boileaus left, the Hall was a

school. Today it is the headquarters of Lotus Cars, but

previous residents have left their mark upon St Peter, as

we shall see. Just as the exterior tells you about the

idiosyncrasies of the residents of the Hall, so the

interior reveals their tastes. There have been four main

families that have left their impression here - the

Grays, the Heveninghams, the Atkyns and the Boileaus.

The atmosphere of the interior, at once rustic and grand,

tells you that the Boileaus had more say here in the 19th

century than the ecclesiologists of Oxford and Cambridge

ever did. Sir John Boileau, the hot-tempered,

paternalistic Squire, was responsible for the elegant

west gallery. He spent thirty years in dispute with the

vain, egotistical, Calvinist rector William Andrew and

his appalling wife Ellen, a long series of events

recounted in detail by Chadwick's book.

The key lets you in through the vestry, and you step into

a chancel which is quite overwhelming in the quantity of

its memorials. There are over 500 years worth of them

from all four families, and the best thing is that they

are almost all both interesting and quirky. Few of them

are merely pompous or run of the mill.

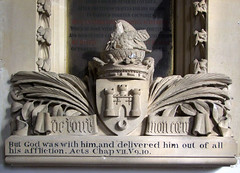

There are, broadly speaking, four

groups. On the south side of the chancel is a large table

tomb which might once have formed an Easter sepulchre.

Set in its recess are two late 15th century brasses to

Sir Henry and Lady Gray. An older brass to Jane Gray is

set on the wall to the west of it. Moving west, the

massive tomb by Robert Page is for Edward Atkyns, who

died in 1750. It looks like nothing so much as a bath tub

with lion's feet.

Directly opposite is the family pew of the Atkyns, later

that of the Boileaus - memorials of both families tower

above it, most prominently the weeping woman and urn on

the Richard Westmacott memorial to father and son Edward

and Wright Atkyns. The array of weapons stacked beside

the urn recall that the son died in battle.

This is echoed in one of the later brass inscriptions set

below to Charles Augustus Penryn Boileau, youngest son of

Sir John Boileau. Something of a rake, he went to the

Crimean War as a way of escaping his debts, and died in

Malta on his way home as a result of injuries suffered at

the 1855 siege of Sebastapol. A tangle of musket, sword,

bugle is starkly carved from stone beneath.

A memorial of similar size to John, Charles' eldest

brother, matches it. He was more successful in public

life than his brother, for he was a parliamentary private

secretary to Lord John Russell. Russell's retirement

coincided with the end of the Crimean War, and John

rushed out to see it end, but caught a fever in

Austro-Hungary. He came home, but was sent to the south

of France to recuperate. He got as far as Dieppe, and

died there in 1861.

Between the two brasses is a central, larger one to their

parents. Sir John Boileau, his movements, talents and

emotions known to us today from Chadwick's book, was a

bull-headed yet sympathetic character who might have

stepped out of the pages of Trollope. He lies here now

with his wife Catherine. Catherine should have been

remembered by a memorial window depicting the saint that

shares her name, but rector William Andrew fanned such an

uproar in the parish about having an image of a Saint in

the church that Sir John eventually relented. The rector,

who was not unkind, reported to Sir John that his

greatest fear was that the simple people of the parish

might think it was the Virgin Mary.

Perhaps the most curious memorial is the most westerly

one of this group. It is a 1910 memorial to Charlotte

Atkyns who died in Paris in 1836, and is buried in an

unmarked grave. Born a Walpole, she found herself caught

up in the French Revolution. her inscription

recalls that she was the friend of Marie Antoinette, and

made several brave attempts to rescue her from prison.

After that Queen's death she strove to rescue the Dauphin

of France. She bankrupted the family fortunes in her

quest, mortgaging the Ketteringham estate and claiming to

have spent an extraordinary eighty thousand pounds, about

fifteen million in today's money.

Owen Chadwick recalls that, on her death, she requested

that her body be returned to Ketteringham and a marble

slab be placed on the chancel walls. Her relatives of the

time, left destitute by her enthusiasms, not unreasonably

failed to carry out either request. You might think that

Charlotte's Francophile adventures and the French name of

the Boileaus might indicate a family connection, but in

fact the Boileaus were an old Huguenot family who came to

Norfolk by way of Dublin, and already owned Tacolneston

Hall. They bought the bankrupt Ketteringham estate after

Charlotte's death.

Perhaps the best of all the memorials is in the

north-east corner of the chancel. It is to Sir William

Heveningham and his wife Mary. It is curious, for the

figures and prayer desk at the bottom and the ascending

angel above appear to obscure the inscription, but there

may be a reason for this. Sir William was one of those

who sat in judgement on Charles I, and although he did

not actually sign the death warrant, he was deprived of

his inheritance, and for many years his name was under a

cloud.

So this church is obviously worth the visit for the

memorials alone, but there is rather more to it than

that, for here is has one of the best collections of

medieval and Flemish glass in central Norfolk. One of the

most interesting aspects of the collection, given that

the Hall was in the hands of four powerful families over

the centuries, is that it includes a 15th century Grey

arms, and so we may perhaps assume that the families that

collected the later continental glass were adding it to

English medieval glass that was already in situ. The most

important glass is an English medieval Coronation of the

Queen of Heaven, a relatively rare pair of panels. Also

English are numerous angels, a Saint Cecilia playing her

psaltery, and a Bishop. St Christopher carries the Christ

child while a hermit looks on. Continental roundels

include St Barbara, St John the Baptist, St James, the

Blessed Virgin prsenting the infant Christ to the young

St John the Baptist. A couple of the roundels appear to

be rebuses.

One of the striking things about

the glass is that this is obviously a collection set for

display. I assume that this was the work of the late 18th

century Atkyns family. Mary Parker tells me that the

entire window was reset in 1908 by the King workshop of

Norwich, and that some of it is now in reverse order to

that given in an account of 1851. Some of the panels are

in poor condition, and I fear that this may be because

they were originally set back-to-front, that is to say

with the painting outside, exposed to the elements. The

King restoration corrected this, but not before the

damage had been done.

At the other end of the church below the gallery, the

late 15th Century font is curious. Four of the panels

feature evangelistic symbols, and two others roses, but

the final two panels are the only two that appear to have

suffered deliberate damage. One is clearly a crucifixion

scene, something like that which you find often on fonts

in the seven sacraments series. The eighth panel is

harder to decode. It shows a figure holding a staff,

perhaps the Resurrection.

The renewed roof, with its restored angels, is set on

interesting corbels, and there is a good view of them

from up in the gallery. This is a small, narrow church,

and the intimacy of the views from aloft is striking. In

such a small building it even gives a good vantage point

for photographing the east window if you have a decent

zoom. Sir John Boileau built the gallery as a way of

providing seating for the Sunday School, an interference

that the Rector deeply resented. There was no way that

Sir John's liberal paternalism and the Rector's

fundamentalist intransigence were ever likely to

accommodate each other. The firm security of tenure

enjoyed by both, and the further sources of friction that

arose between them, not least the interference of the

Rector's wife, made the situation explosive.

All around are hatchments of Atkyns and Boileaus. There

is no doubt that they had their say, but strangely enough

there is no sense of triumphalism. Rather, they mark a

church which was a real backwater, both geographically

and in terms of English church furnishing and decoration.

But if this was a backwater, it was a moneyed one. There

is a quality to the way everything was carried out here,

and this remains today. As a good example, take the late

16th century painting on boards of the Wedding at Canaa

in use as a reredos. My goodness, what a thing to find in

an English country church! At the time it was painted, we

were all enthusiastic protestants, stripping our churches

and our lives of things of beauty. But here it is, an

extraordinary Flemish survival, probably collected in the

early 19th century.

What must it have been like to attend divine service here

in the 19th century? I assume that the entire parish,

pretty much, worked for the Hall. Whose side were they on

in the long-running dispute between Squire and Rector?

The Rector had the advantage of a three-decker pulpit.

The reading light now faces north-west, but at one time

he would have faced north-east, to address the Hall pew.

This must have given him something of an advantage on a

Sunday. But today it is the Hall families we remember,

the Grays, the Heveninghams, the Atkyns and especially

the Boileaus. So, spare a glance and a thought before

leaving for the cold stone memorial on the south nave

wall for William Wayte Andrew, Rector through the middle

years of the 19th century. In his evangelical Calvinist

zeal he faced up to the Boileaus, but it must be with

pursed lips that he is a silent witness to them now.

Simon Knott, April 2020

Owen Chadwick's Victorian Miniature is available from amazon.co.uk

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

|

|

|