| |

Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, Little

Walsingham

(Anglican

Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham)

In the Middle Ages, the shrine of

Our Lady at Walsingham was second only to the Shrine of

St Thomas of Canterbury in its significance to English

pilgrims. The statue of the Blessed Virgin and child was

contained within a holy house, supposed to be a replica

of the building in Nazareth where Mary had received the

news of her pregnancy from the Angel Gabriel. It was said

that the angel had appeared to Richeldis, a noblewoman,

in a dream, and asked her to construct the building. By

the 12th Century, a large Augustinian Priory had grown up

here at Little Walsingham, and pilgrims, unable to visit

the real Nazareth in the Holy Land because of the

Crusades, came to England's Nazareth instead.

It was not to last. Pilgrimage, and the means of Grace

which it sought to effect, were heavily frowned upon by

the Anglican reformers of the 16th Century. The Crown had

its beady eye on the wealth of pilgrimage sites, and so

in the 1530s they were abolished by royal decree, their

communities dispersed, their furnishings burnt or sold,

their money accruing to the Crown. The statue of Our Lady

of Walsingham was burnt at Chelsea, although it has been

suggested that the statue in the Victoria and Albert

Museum known as the Langham Madonna may actually be the

Walsingham statue, either rescued or sold. A heavy

silence then descended on Walsingham. It was not

difficult for such a remote place to become a backwater,

and 16th Century recusants, along with antiquarians of

the 17th and 18th Centuries, bemoaned its desolation.

The story of Walsingham begins again with the

decriminalisation of Catholicism in the 1820s. This had a

two-pronged effect. Firstly, a group of Anglican

intellectuals at Oxford were appalled by the possibility

that the Church of England might become nothing more than

a protestant sect, and sought to proclaim what they saw

as the true Catholicity of a National Church. Secondly,

the rapid emergence of Catholic communities in England

led to the re-establishment, in 1851, of the Catholic

hierarchy. For the first time since the Reformation,

England had Catholic parishes again.

It has to be said that neither of these two events made

much of an impression on Walsingham. There were few

ripples to be noticed in this backwater of 19th Century

England. It was not until the 1890s that a Priest at the

Kings Lynn church of the Annunciation, the Catholic

parish into which Walsingham fell, built a Marian shrine

within the Kings Lynn church, dedicating it as the Shrine

of Our Lady of Walsingham. That same decade, Charlotte

Pearson Boyd, a convert to Catholicism, bought the

Slipper Chapel at Houghton St Giles and gave it to the

Diocese of Northampton for Catholic use. This is now the

heart of the Catholic National Shrine of Our Lady, but in

the 1890s the Bishop of Northampton seems to have been a

little embarrassed by it, and the statue remained at

Kings Lynn.

All this was happening in the background, then, when the

main Anglican player entered on to the stage, a man whose

name will be forever associated with the story of

Walsingham. Alfred Hope Patten was a convinced

Anglo-Catholic, and in 1921 he arrived in this Church of

England parish which already had firm Anglo-Catholic

sympathies. A young man, he brought the energy of the

movement to this rural outback, and one of his first

actions was to install a replica image of the medieval

statue of Our Lady of Walsingham in the Little Walsingham

parish church.

This was a fairly provocative act for the time. The

Church of England was at the apex of its cultural

influence, thanks largely to the way in which it had

ministered the experience and the grief of the First

World War. It had a central place in the English

imagination. The Anglo-Catholic Movement was in its

ascendancy, at the peak of its enthusiasm.

Anglo-Catholics seemed to challenge the Anglican

consensus at every turn. They would shortly attempt to

have the Church of England replace its totemic Book of

Common Prayer, in use for some 350 years, with a new

prayer book. This would fail, and in retrospect the

Anglo-Catholic tide began to recede at that moment. But

that was all in the future.

The Anglican Bishop of Norwich was outraged by Hope

Patten's statue, and demanded that it be removed. Hope

Patten carried out this request in considerable style,

translating the image to a new location on the other side

of the Priory ruins, and building another replica of the

holy house of Nazareth around it, just as had happened

some 750 years previously. Hope Patten believed that the

pendulum of the Church of England was swinging his way,

and that the views of the Bishop would one day come to be

seen as of a past age. There were enough militant

Anglo-Catholics in positions of influence to ensure that

Walsingham had powerful friends. The new shrine soon

began to generate interest, and it was not long before it

became necessary to build a larger church around the

shrine, which was completed shortly before the outbreak

of World War II. This was substantially extended in the

1960s, giving the building the shape and appearance it

has today. It has to be said that the 1930s was not a

good time to be building a new church or extending it.

The exterior is very much in the spirit of that decade.

The main entrance is ostensibly from the west, but in

practice the extended church has arcading which opens

onto the shrine gardens, which have been developed

extensively as a place to sit or wander, and are enclosed

by early 21st Century buildings which include offices,

hostels and a refectory.

Inside at the west end of the

church there are steps down into the holy well,

supposedly discovered after Hope Patten paused in prayer

above it. There is a large ceramic relief of the

Annunciation here. Behind this is the Holy House itself,

lit up inside by hundreds of candles which burn here

daily for Anglo-catholic parishes and intentions from

around the world. The grand altar is surmounted by the

splendidly dressed replica of the original Walsingham

statue, glittering in its finery. Altar, reredos and

baldachino are the work of Ninian Comper, who also

designed much of the glass, although there is also a

delightful Annunciation window by Trena Cox, one of only

two of her works in East Anglia. In the arcades around

the Holy House are memorials of militant Anglo-Catholic

priests of the late 19th Century, from the time before

their extraordinary movement reached out and touched this

place. It is all a world away from the simplicity of the

Catholic shrine a mile off at Houghton St Giles.

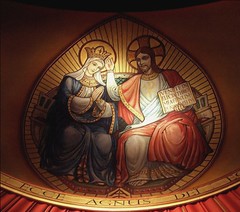

Beyond the Holy House, the shrine church opens up and

extends into a labyrinth of chapels on two levels. There

are fifteen of these, allowing the rosary to be said, one

mystery in each chapel. One of the chapels is dedicated

and consecrated for Orthodox worship. Others are altars

for particular Saints or causes. Whichever way you go,

you eventually end up in the Blessed Sacrament chapel

with its ceiling mosaic of the Coronation of the Blessed

Virgin, above the high altar. It is a moving experience.

Perhaps it is fair to say that the shrine never made it

to the heart of Anglicanism in the way that Hope Patten

had envisaged. But in another way, it has reinvented

itself, along with the mainstream of the Church of

England, to stand as a witness to the Faith for the

hordes of tourists and visitors who make their way to

Walsingham. They come here with their hunger for the

spiritual, their God-shaped holes, and enter a sense of

the numinous which has a like nowhere else in England.

God moves in mysterious ways.

Simon Knott, February 2023

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

a video

exploration of Walsingham's history and places

|

|