| |

|

Holy

Trinity, Marham

|

|

We

came to Marham at the end of a busy day, and at

last the shower broke. It had been threatening

all day, but it did not last long. In the wake of

the rain, the sun broke out more strongly than

before, and the graveyard of Holy Trinity was

filled with the intense fragrance of high summer.

The birds recommenced their busy chatter, and

insects lifted across the high grass in the

rising heat. It was as lovely a place as we had

been all day. I was travelling with local

historian Paddy Apling, who is a retired food

scientist. In just one corner of Marham graveyard

he identified no less than twelve different

species of wild grass, at least one of which was

rare. The dead of Marham lay all around.

These days, I suppose, the parish is best known

for the huge air base which lies between here and

Swaffham, but this was also a busy place in early

medieval times. Domesday noted two churches, and

on the north side of the nave is a grand Norman

doorway of a style which Sam Mortlock observed is

found only once elsewhere in Norfolk, on the

north transept of Norwich Cathedral.

|

Otherwise,

the church is largely a result of the local farming

wealth of the 14th and 15th centuries, and you step into

an interior which still speaks of that period. The arcade

which separates the nave from the south aisle is from

towards the end of this period, while the font is a

fairly spectacular example of the early 14th Century, its

panels depicting a variety of Decorated tracery.

On the

other side of the great Reformation divide is one of

Norfolk's best sets of James I royal arms, curiously

placed inside the north wall of the tower, where many

people must miss it.

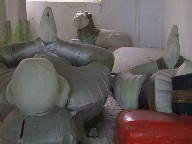

There is a

most curious sight at the east end of the south aisle. As

the Tudor period ended, and the puritans began their rise

to power under the early Stuart kings, there is a rapid

deterioration in the quality and style of English

memorials, a result perhaps of puritan suspicion of the

vanity of art and education. In 1604, John Steward and

his wife were buried here under what looks like half of a

fairly monstrous six-poster bed, their sleeping effigies

watched over by a maudlin lion and garishly recoloured in

recent years. Folding chairs and a large display screen

had been stacked against it, as if the parish were

faintly embarrassed by it, and perhaps no wonder. We put

them back carefully after photographing the thing.

| Aside

from this, I liked very much the sense of a busy

19th Century piety in this church, all of a piece

with some of the fine Victorian houses on the

road to Shouldham. It is easy to imagine the

minor characters of certain Trollope novels

making their way down the village street of a

Sunday to settle themselves into the pews. One of

those 19th Century worthies, Henry Villebois, was

thought of highly enough for a memorial to be

placed behind the pulpit to him by the great

Richard Westmacott, a sculptor best known for his

frieze on the front of the British Museum in

London. Two angels rest in contemplation in front

of the inscription. Mortlock was

uncharacteristically harsh about Westmacott's

work, observing that it is competent but

uninspired. In truth, this memorial might

seem more impressive if it was not so awkwardly

placed. Outside, well-carved and substantial

Victorian gravestones kept a kind of

contemplation of their own, peeping their heads

above the waving ocean of Marham's burgeoning

wild grasses.

|

|

|

|

|

|