| |

Glory to God

in the highest, and on earth peace, goodwill toward men.

So sang the angels on that first Christmas morning, and

images of them, and their message, will appear on a

million Christmas cards, usually in the form of gilded

manuscripts or Renaissance paintings, or lurid females in

the Pre-Raphaelite manner.

|

|

That

mediaeval manual of church lore The Golden

Legend, put angels firmly in their place, mid-way

between man and God. Man understood that though

angels are our keepers, our ministers, our

brethren and our neighbours, they were also the

bearers of our souls into heaven and representers

of our prayers unto God, right noble knights of

the King of Heaven, who dwell in the royal hall,

accompanying the King of Kings and singing songs

of gladness to his honour and glory. It is no wonder,

then, that angels had such an important place in

the decoration of our mediaeval churches, or

indeed that nearly seven hundred churches in

England were dedicated to St. Michael and All

Angels.

|

| Look

upward at the timber roofs at Knapton, Swaffham

or Cawston in Norfolk,

March in

Cambridgeshire or Woolpit or Blythburgh in Suffolk,

and the angelic host flutters overhead in

its multitudes, 160 figures at Knapton

alone: angels with spread wings on the

wall-plates, angels standing against the

hammer-beams and on the bosses. Their

groupings suggest that the designers,

whoever they were, wished to present a

structure not only of craftsmanship, but

of worship also. The hierarchy of the

angels, Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones,

Dominions, Virtues and Powers,

Principalities, Archangels and Angels,

dating back to the sixth century and

gleaned from various biblical sources,

including St. Paul’s list of

supernatural beings, is strictly adhered

to, as it is on the screen at Barton Turf.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

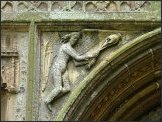

In

sculpture, some of the most moving carvings are

the flying angels high up on the walls at

Bradford on Avon (Wiltshire), probably carved in

connection with a Saxon Rood which no longer

exists. At Rowlestone, in Herefordshire, four

angels fly upside down supporting the figure of

Christ in Majesty and at Salle, in Norfolk,

feathered figures with censers appear on either

side of the west door.. The feathers have the

appearance of a tightly fitting garment, cut low

around the neck, whilst the sleeves end loosely

above the elbows, and the legs are bare below the

knees. Less well known is the carved angel

orchestra on either side of the Annunciation on

the sumptuous porch at Pulham St. Mary - one side for the

wind and one for the strings. |

Inside the

church angels are everywhere. The wonderful angel

roofs of East Anglia have already been mentioned,

but we find angels adorning fonts, bench-ends,

screens and windows. Often they are shown just

from the waist up, known as demi-angels, and

might support the bowl of an elaborately carved

font, as at Upton, or peer out from

behind the figures of saints, as at Litcham. Sometimes they are

given pride of place to themselves, as above the

main figures adorning the side altars at Ranworth.

Angels occur over and over again in ancient

glass, often carrying inscribed scrolls,

displaying the Te Deum, the Nunc Dimittis or

Gloria in excelsis. In churches dedicated to the

Virgin Mary, Marian antiphons are common: Salve

Regina or Ave Regina caelorum. Some carry

shields, and are often carved on the side of

tombs, but the most common accessory of these

mediaeval angels seems to be musical instruments.

|

|

|

|

Paintings,

carving or stained glass, music seems to be

everywhere, and the angelic orchestra contains

the harp, the viol, the organ, the lute (in

various forms,) bagpipes, cymbals, tambours - the

list is endless, and conforms fairly strictly

with Psalm 150: Praise him with the sound of the

trumpet; praise him with the psaltery and harp.

Little remains in situ, but there are excellent

figures at Cawston and Bale, and two particularly well

preserved examples at East Barsham, one playing the

harp and one the cornetto, where the mouthpiece

is carefully depicted. There are countless angels

in sentimental Victorian windows, but the

extraordinary church at Booton has a fine all-girl

orchestra, whilst the angels in the Resurrection

window at Walsoken have a timeless

beauty. |

| There is a

legend that Palestrina composed his Missa Papae

Marcelli under the direct influence of an angelic

host. Improbable, no doubt, but just look up at

the Angel Choir at Lincoln or the vault above the

High Altar at Gloucester, or gaze in amazement at

those hammer-beam roofs in East Anglia and hear

in your mind the chorus of flying angels at the

end of Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand

or the serene angelic voices which close

Berlioz’s L’enfance du Christ,

music that emanates from Heaven alone, shared

between oneself and one’s maker, and in

doing so you can capture some of the spirit and

imagination of those incredible artists and

craftsmen who lavished such skill on decorating

our churches all those centuries ago. |

|

|

Tom Muckley, 1999 rev. 2006

|

|