| |

|

St Helen,

Norwich

|

|

This

great building is the last of the medieval

churches in Norwich city centre to appear on this

website, simply because it is the last one that I

have been able to get into. Previously, I have

always found it locked. It may come as a surprise

to some people to discover that I get no pleasure

from moaning about locked churches. Indeed, there

is something both frustrating and dispiriting

about finding the House of God locked to pilgrims

and strangers. I realise that many Anglican

congregations are shrinking and ageing, and some

of them find it increasingly difficult to manage

the buildings in their care. But I do not think

that can be true of St Helen. Be that as

it may, we came here on one of the open days at

the Great Hospital next door. The irony is, of

course, that the church is also open on these

occasions, partly to allow access to Eagle Ward,

of which more in a moment. But this extraordinary

church is actually the far more interesting of

the two, and it is a great pity that it is not

easier of access.

|

There is

no other church quite like St Helen. You can see this at

once from outside in Bishopgate. The great length of the

church is hidden behind a high wall, with one of the two

long south transepts forming a porch-like entrance. You

don't need to go beyond the wall to tell that St Helen is

part of a great complex of buildings which adjoin it to

north, east and west. This is the Great Hospital, a

community of almshouses still in use for essentially the

same purpose as it has been for 750 years.

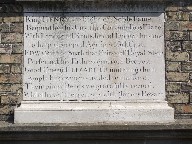

Above the

entrance door to the church is an 18th Century Protestant

triumphalist inscription: King HENRY the Eighth of

Noble Fame Bequeath'd this City this Commodious Place.

With Land and Rents he did Endow the same to help

decreped Age in woful Case. EDWARD the Sixth that Prince

of Royal Stem Perform'd his Fathers generous Bequest.

Good Queen ELIZABETH imitating them Ample Endowments

added to the rest. Their pious Deeds we gratefully record

While Heaven them crowns with glorious Reward. Thus,

in rather long-winded form, we learn that, after the

Protestant Reformation, the ownership of St Helen and the

Great Hospital passed to the City of Norwich.

It had

been founded three hundred years before the Reformation

by Bishop Suffield, who bequeathed in his will, as Sam

Mortlock succinctly records, that a Master and four

Chaplains should pray for his soul, and minister to

indigent clergy, the aged sick and seven poor scholars.

The building was essentially an infirmary with a chancel

attached. The chancel was rebuilt towards the end of the

14th Century by the notorious Bishop Despencer, possibly

to give thanks for his success in helping put down the

Peasants' Revolt, and the body of the church itself,

along with the cloisters and their adjoining buildings,

was completely rebuilt about a hundred years later. Over

the centuries since, the complex has grown, with some

particularly fine 18th and 19th century buildings to the

north and west. There is no graveyard, and the courtyards

around tower and chancel are maintained as attractive

gardens for the residents.

You enter

the building through the south nave transept, which forms

a huge, light, vaulted porch, and it is with some

surprise that you step into what is actually a small,

square space beyond. The chancel is blocked off at the

chancel arch. The aisles and the side chapel in the other

transept accentuate the width of the building. The

western part of the nave was blocked off beyond the third

bay of the arcades at the Reformation to form an

infirmary, and a small window high in the wall actually

lets into the stairway which runs up the partition wall.

The chancel was a huge space, the biggest chancel of any

medieval church in Norwich, and in the late 16th Century

it was split into two floors to form wards for the

Hospital, one for men and the other for women.

Something

else is strikingly unusual about St Helen, and this is

that it retains its 18th century liturgical integrity.

Until the Oxford Movement was so spectacularly successful

in reinforcing the sacramental layout of Anglican

churches in the 19th Century, the main focus in any

Anglican parish church, for almost three hundred years,

had been the pulpit rather than the altar. At St Helen,

the altar was never moved back to the middle of the east

wall, and it remains in the transept chapel. Instead, the

grand pulpit still dominates the eastern end of the

church, making this a properly Protestant interior.

The 18th

Century theme continues into the transept, with a

gorgeously coloured reredos backing a simple holy table.

Either side are memorials to former Masters of the

Hospital. However, whereas the nave is overwhelming in

the whiteness of its walls and the bareness of its wood,

giving the feel of a Dutch Protestant church, the

transept has a most beautiful vaulted ceiling, painted

blue with white and gold ribbing. The bosses on the

ribbing are vividly repainted, and are one of the most

important sets in England. They are obviously in the same

series as those in the Cathedral next door, with a more

idiosyncratic, even folkish quality than those found more

commonly in East Anglian parish churches - for example

Wymondham Abbey, Walpole St Peter and Lowestoft St

Margaret, where they are more formulaic. Probably, they

are by the same artist as those in the Cathedral nave.

They are

arranged in the shape of a star lattice, with th most

important boss at the centre. This is the Coronation of

the Blessed Virgin as the Queen of Heaven, the most

significant event in the unfolding revelation of Grace in

the medieval imagination. Arranged to north, south, east

and west are four significant events in the Christ story

- the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Resurrection and

the Ascension. The Annunciation is exquisite, with St

Gabriel's Ave Maria exultation curling on a

banner around the lily stem. The Nativity boss appears

unusual at first sight, the naked Christ standing on a

table with a blanket held behind him, and you might even

take it to be the Circumcision if it were not for the

cattle and angels peering over the wooden stable roof

above. In fact, this is the only Nativity boss in England

in this form, and the only one to depict a midwife. The

Resurrection and Ascension scenes are more typical. The

other bosses depict Saints and sacred monograms.

The

transept also contains the family pew of William Ivory,

and both aisles contain lovely box pews which face across

the church. I'm not convinced that the range of benches

in the middle of the nave came from this church

originally, although there is a suggestion that the brief

inscription beneath the bench end of St Margaret refers

to an early 16th Century Master of the Hosptial. I can't

help wondering if there were once box pews in the middle

as well, without a central gangway.

| If

you leave the church by the north door, you enter

an exquisite set of cloisters, like those of the

cathedral but in miniature. A path leads through

to the former priest door on the north side of

the chancel, and this in turn leads into a

stairway. There is still an institutional smell

of disinfectant, and the wooden stairs have been

worn away by generations of hobnailed boots. The

lower floor is now used for storage space, but

you can go up the staircase into Eagle Ward,

which has been perfectly preserved as it was when

it finally closed - astonishingly, this is was as

late as the 1970s. The Ward

stretches the full length of the former chancel.

The great east window was blocked in the 16th

Century, and at the west end you can see the

other side of the blocked chancel arch; but

because we are in the upper part of the divided

chancel, the tops of vast 14th century windows

flank both north and south walls, providing a

surreal backdrop to the poignant little cubicles

with their beds and dressing tables, still

furnished with ornaments, books and magazines. At

either end of the ward were the snugs, where

residents could come together, and there are

dining tables the length of the central walkway.

A fascinating survival.

|

|

|

|

|

|