| |

|

St John

the Baptist Maddermarket, Norwich

|

|

The

church is popularly known simply as St John

Maddermarket, and is famous for being the church

where the morris dancer Will Kempe ended his nine

days dance to Norwich from London in 1599. A

square church, and a familiar sight to shoppers,

where the pedestrianised identikit shops of

London Street give way to earthier Pottergate.

The suffix Maddermarket comes from adjoining

Maddermarket Street, and suggests a place where

dye for clothes was sold. The church was rebuilt

in a determined Perpendicular style in the late

15th Century. The nave is wide, the clerestory

unusually high. Was there ever a chancel? If so,

it had been demolished by the end of the 16th

Century, but there may well have never been one,

since the three east windows appear to have the

oldest tracery in the building. The south

door sits on the busy street, the north door is

reached by a long passageway past the

Maddermarket Theatre. There are no proper

porches, the north and south doorways opening

directly into the aisles. In the early 20th

Century they were joined by a narthex built under

the west gallery, echoing the processional way

which runs beneath the elegant but hemmed in

tower. This emphasises the sense of a church

which is wider than it is long.

|

George

Plunkett's photographs show the church as it was on the

eve of the Second World War, both views still fairly

familiar today. The church was declared redundant in the

early 1970s as a result of the Brooke Report, which is

perhaps understandable given the proximity of St Andrew

and St Peter Mancroft. For a while, it was used by the

Greek Orthodox community, but the building came into the

care of the Churches Conservation Trust, and is regularly

open, although perhaps not as often as it might be given

its location.

Stepping

inside to the dark, devotional interior, you might be

forgiven for thinking that the Greeks were still in

possession. In fact, this faux-baroque space is almost

wholly the work of William Busby, arch-Anglo-Catholic

Rector in the early years of the 20th century, much of it

collected from other churches, the rest made to his

orders. There is a feel, not so much of clutter, but of a

crowding within the enclosing walls of late 19th and

early 20th Century glass, and not even the dominating

18th Century baldachino, originally made for St Michael

Coslany, can fully draw the eye eastward without

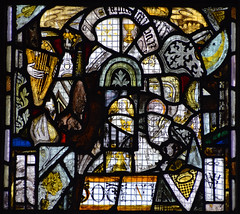

distraction. Some fragments of medieval glass survive,

but much that was old was destroyed in a gas explosion in

the 1870s. A few noteable survivals are elsewhere, as we

shall see in a moment.

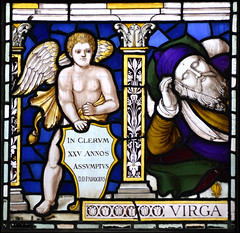

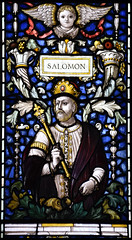

With the

exception perhaps of the 1870s east window installed

after the explosion, the glass is good of its kind. In

particular, Powell & Sons's Annunciation scene in the

north chancel chapel is outstanding.

The east window in the

south chapel, which is probably also by Powell &

Sons, depicts the Blessed Virgin surrounded by angels

holding shields of the instruments of the passion beneath

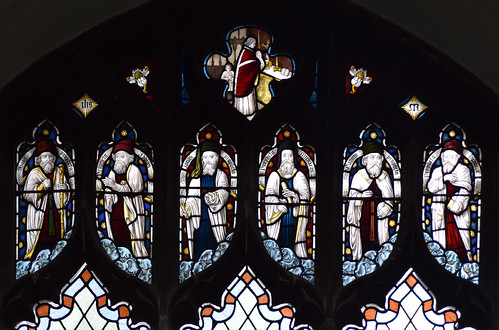

six female Saints in the upper lights. But it is the

other window on the south side above the priest's door

which is most memorable, showing a splendid Tree of Jesse

by the J&J King workshop of Norwich, installed after

the First World War. It is hard not to think that the

faces of the prophets are actually Norwich worthies of

the time.

Missing from the

church is the medieval rood screen, which must have run

right the way across the nave. Surviving from it are some

of the panels, depicting Saints including St Agatha and

St William of Norwich, but today they are in the Victoria

& Albert Museum, along with some glass from a Norwich

church which is also likely to have been St John

Maddermarket.

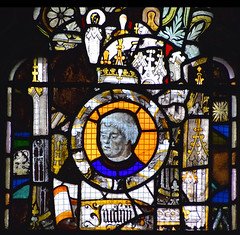

| Among

the surviving medieval fragments still in the

church are a fine figure of St Edward the

Confessor, and a heavily restored Christ figure

from a Coronation of the Blessed Virgin scene. St John

Maddermarket's splendid Anglo-catholic

reimagining by William Busby rather pushes the

number of memorials, both in brass and stone,

into the background, but they are worth a look.

Among them are the brass of John Tuddenham, who

died in 1450. He has a complete prayer clause

inscription in English. From the other side of

the religious divide are the two Sotherton

memorials, one of 1540 and the other of 1606, the

couple in each case facing each other across a

prayerdesk.

The

Sothertons were exactly the kind of family which

powered the English Reformation, mayors and

merchants who had benefited from the Black

Death's freeing up of capital and land to rise to

prominence. And here they are today, in all their

glory.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, December 2017

|

|

|