| |

|

St

Laurence, Norwich

|

|

One

of the staggering experiences of the church

explorer in Norwich is the sheer proximity of one

church to another. In a little over four hundred

yards, you can walk past five redundant medieval

churches in the length of St Benedict's Street

alone, from the back of St Gregory to the ruin of

St Benedict itself. One of these churches, St

Swithin, is now the Norwich Arts Centre, while St

Gregory and St Margaret have occasional uses for

exhibitions and concerts. That leaves

St Laurence, the biggest of the five, a grand and

prominent landmark now in the care of the

Churches Conservation Trust; without their loving

care it would be little more than a rotting

corpse. As it is, it is quite the biggest empty

shell in the middle of Norwich.

|

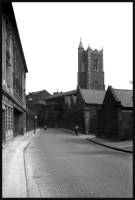

| It

was not always so, of course. This was one of

half a dozen large city centre churches

completely rebuilt during the 15th century. It

took about sixty years, but nevertheless St

Laurence is all of a piece, a textbook

Perpendicular church. From St Benedict's Street

it is not immediately clear quite how vast this

building is; it is the third biggest medieval

church in Norwich after St Peter Mancroft and St

Andrew, bigger even than St Stephen. The

clerestory is 12 windows long, and the mighty

tower almost 120 feet high. It is more

imposing from Westwick Street, standing high

above the street like a fortress. For pedestrians

coming into central Norwich from Coslany, it is

like a gateway to the city, far more impressive

than the city walls. The spired stair turret on

the tower is castle-like, especially in George

Plunkett's 1938 images.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

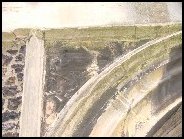

One of the most

interesting aspects of the exterior is the west

doorway, easily missed and seen only from the

narrow St Laurence's Passage. The spandrils

feature two exquisitely carved martyrdoms, quite

undamaged by time or the hand of iconoclasts. One

is that of St Laurence himself, and shows him

tied to the gridiron while the fire is prepared

(St Laurence being the patron saint of those who

cook on barbecues) , and the other is of St

Edmund shot full of arrows. You can see them on

the left. |

Above the passage, the great tower's height

is accentuated by the narrowness of the gap to its left.

And the unbroken length of the nave and chancel is so

high, too; the north side drops away to Westwick Street,

and the floor takes this as its level. You step down a

flight of stairs into the south porch, which is otherwise

hard against the street, thanks to widening for trams in

the late 19th century, and then through a 15th century

door down into the church itself..

The sheer scale of this building is only

apparent once you are inside. The roof seems absurdly

high, the 1490s hammerbeam roof lost far off in the

shadows. The arcades are less elegant than forceful, and

the unbroken line, with no chancel arch, marches

purposefully eastward.

|

|

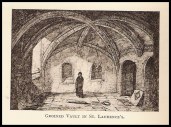

This

is all accentuated by the fact that St Laurence

is pretty much completely empty. Almost, but not

quite. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries,

St Laurence underwent an extraordinary makeover. In a city

renowned for the excesses of its Anglo-Catholic

churches, this was among the highest of the high.

The sanctuary had always been raised above the

level of the chancel because it goes over a large

vault, shown in the old engraving on the left, as

at Tunstead. But here the entire easterly third

of the building was elevated by the late

Victorians into a great platform, a flight of

steps leading through a stone screen and then

again to the sanctuary, until the altar was fully

twelve feet above the floor of the nave.

|

| George

Plunkett's 1938 image shows the interior with

Victorian benches and a passageway accentuating

the view east. The altar and reredos are

now gone, but the painted panels that flanked

them survive. They depict angels and Saints, but

the most curious thing about them is that all the

faces are drawn from the life, little Edwardian

boys and youths cloaked out in contemporary

clothes, but wearing nimbuses and holding gilded

symbols, and older men with wings and in armour.

It is all at once grotesque and fascinating. The

reredos they flanked was the Parish war memorial,

so they may be even later than they appear. The

screen to the north aisle chapel has panels

painted in a similarly naive manner. I strove to

understand what it was that had possessed people

to do this, but I could not.

|

|

|

|

|

There is a

15th century font contemporary with the rebuilding of the

church, and a scattering of medieval glass has been built

into an abstract design in the north aisle chapel. There

were brasses, but these were removed; first to St Peter

Hungate, and then into storage when the museum there

closed.

| St

Laurence was one of the 24 Norwich churches

recommended for demolition by the Brooke Report,

a shocking possibility that galvanised Lady

Harrod and others into forming the Norfolk

Churches Trust to defeat the philistines. Under

the circumstances, it seems ungrateful for us not

to actually do anything with the place.

My friend Tom tells me that this church has a

wonderful acoustic, and in truth it is hard to

see it ever having any use other than for

performance or liturgy - it is simply too big for

conversion into anything else. Its shell is

recognised today as a vital part of the Norwich

townscape, and that at least is now safe for

future generations; but will it ever again be

anything more than a shell? |

|

|

Simon Knott, November 2005

|

|

|