| |

|

St Paul, Norwich

Norwich and Bristol

were the only towns outside of London to be large on a

European scale during the Middle Ages. One of the results

of this is that Norwich still had 36 parish churches in

its city centre when the Reformation happened; a couple

were rapidly demolished, but most lingered on into the

20th century. Over the years, the parish function of some

fell into disuse, but a surprising number were still

parish churches of the Church of England until within the

living memory of many Norwich people.

|

|

|

|

George Plunkett took the

photograph on the left in the 1930s, it shows the

church of St Paul in its pleasant tree-lined

graveyard on the northern side of the city

centre. Here in Coslany and Pockthorpe, outside

of the central commercial area, the medieval

streets had given way to factories and the

terraced houses where the workers lived. But

still the medieval churches made their presence

felt: St Paul was across the road and about 60

metres to the west along Barrack Street of St

James; barely 100 metres in the other direction

was St Saviour. All three churches remained in

use, and St Paul had the most populous parish of

the three. Its round tower, one of five in the

city, was the biggest of them all. |

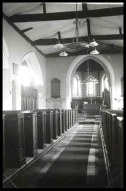

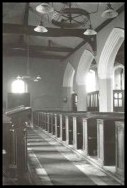

George's

photographs of the interior show a church that

was substantially Victorianised inside, but

retaining two medieval features, the 15th century

font and a parclose screen to the chapel in the

north aisle.

That

this large, aisled church no longer exists is

down to the twin-pronged nemesis of 20th century

Norwich: Adolf Hitler, Fuhrer of the German Third

Reich, and Herbert Rowley, Norwich City

Engineer-in-Chief. Between them, these two men

made sure that no trace whatsover, nothing at

all, remained of a building that was a touchstone

to generations for more than 900 years. Or,

almost nothing.

Cautley

came here after the blitz, but was still able to

see the tower, the two-storied porch and the

north aisle. This is because, contrary to what

you might expect if you've read the history of

the city, St Paul was not completely destroyed,

but burnt out by incendiary bombs. It would have

been quite possible for it to have been rebuilt

if there had been a will to do so.

|

|

|

George

Plunkett's late 1940s photograph of the ruins

(left) shows St Paul as Cautley found it. George

was standing to the east of St Saviour, facing

across Barrack Street, the weeds at his feet

filling the site of a former factory. The spot

where he was standing is now a car park. St Paul

had been restored in the 19th century, a little

apse added to the chancel, but the structure is

still discernible as that of a 15th century

Perpendicular church against a Norman round

tower. There had been a little spirelet on the

top of the tower, which was burnt, but the tower

itself was completely sound, and could easily

have been kept. |

However, in the white heat of post-war

reconstruction, Herbert Rowley seized the chance to shave

a few hundred metres off of the inner-ring road. Instead

of allowing it to circumnavigate the city outside of the

medieval walls as the Norwich post-war plan proposed, so

that its northern part was beyond St Augustine, Rowley

insisted that it should make its journey further south,

cutting off the top quarter of the medieval city from the

centre. The City Station had been destroyed, and so this

was an obvious place to bend the road eastwards, cutting

Magdalene Street in two and joining up with the old road

at the Nelson Barracks corner.

The problem with this was that three

medieval churches were in the way. St James and St

Saviour had survived the blitz pretty much intact, so

Rowley put the new St Crispin's Road immediately to the

north of them, the line running along that of Barrack

Street. However, as the ring road is four lanes and

Barrack Street was only two, this necessitated widening

it, taking it across the site of St Paul.

| The

church was rapidly demolished - although, as I

say, the tower need not have been - and the St

Crispin's flyover over Magdalene Street now comes

back down to earth on the site of south wall of

the nave. Where the tower was is now a children's

playground, and you can just make out - or is it

wishful thinking? - bumps in the ground that show

where the tower was. The two

rows of terraced houses, perpendicular to each

other, were there when the church was, and the

large trees that line the square are the only

survivors of the graveyard - they were there when

St Paul was a parish church. But that's all. And

so, Herbert Rowley's attempt to turn at least

part of Norwich into East Anglia's equivalent of

Wolverhampton began to bear fruit.

|

|

|

The massive urban clearway rises high above

the roof tops, coming down to intersect with the Cromer

road at a huge roundabout. St James, now the puppet

theatre, faces across the roundabout to the site of St

Paul. The two churches were so close, and yet

once terraced houses separated them.

To the north and west of the surviving

terraced rows, much of the medieval parish has now been

demolished, to be replaced by two of Mr Rowley's worst

legacies: the ugly Anglia Square shopping centre, and the

jaw-droppingly awful Sovereign House, formerly home of

Her Majesty's Stationery Office when such a thing

existed, but now standing empty. This is is simply one of

the worst examples of 1960s commercial development in

England, now a run-down, soulless concrete block. It is

completely out of scale; although it is no more than ten

storeys high, its sheer bulk imposes its arrogance on the

little streets around. I travelled widely in Eastern

Europe under the communists, but I don't think I ever saw

anything as bad there in a city of a similar size.

| When

ever I hear anyone complain about the elegant

Scottish Parliament building I want to bring them

to Sovereign House and say 'here, look at this',

and point them at this hideous, brutal block and

its ugly, ugly neighbour Anglia Square.

The current Norwich plan proposes that both be

retained and refurbished, Sovereign House as a

hotel or flats. The ghost of Mr Rowley continues

to cast a long shadow. Beyond them to the north

sits the pretty little medieval church of St

Augustine, once organically part of the medieval

city, but now so cut off from it that it might as

well be in Poland. In common with most cities

of its size, Norwich's central area has recently

been divided into zones, and this part of the

city is called 'St Paul'. And so it is that on

the parking restriction signs around the

playground, the name survives of a building that

it is almost impossible to imagine now.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, December 2005

|

|

|