| |

|

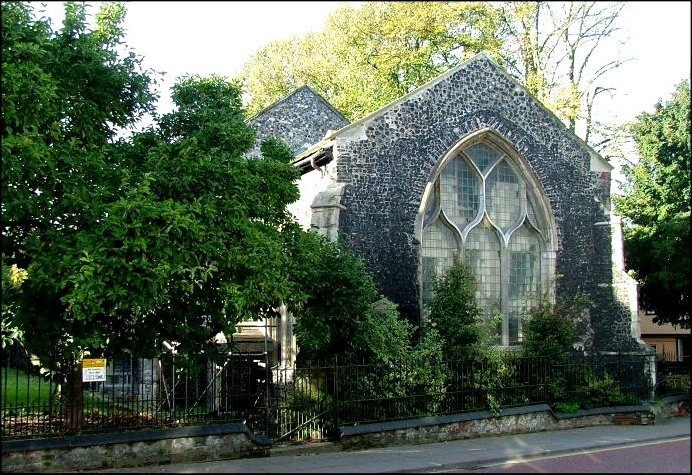

St Simon

and St Jude, Norwich This poor, battered little church

has played an important part in modern Norwich history,

because it was its projected demolition in the 1920s that

galvanised the Norwich Society into action. After a

fierce battle against the City Council, they saved St

Simon and St Jude along with the rest of Elm Hill. After

the war, their reputation made them a powerful voice

against the lunatic policies of Norwich planning officer

Herbert Rowley and his attempts to turn the centre of the

city into some kind of soviet-inspired industrial zone.

St Simon

and St Jude had been declared redundant in the 1890s;

small wonder, as it is within 200 metres of five other

churches, not to mention the Cathedral just across the

road. It was neglected, and in 1911 the tower collapsed.

Shortly afterwards, the building seems to have been

pressed into use as a Sunday school by the neighbouring

churches; but by the 1930s it had been abandoned, and was

an ivy covered-ruin, rapidly returning to earth.

|

|

On

the afternoon of Wednesday, March 16th 1938, the

young George Plunkett photographed the

ivy-covered mound from Fye Bridge Street. A lone

policeman stands, gazing at the disappearing

church. You can just make out the west face of

the tower stump, gone today. George

managed to get inside as well, and took the

extraordinary photographs below. They show an

abandoned interior, but still with its stove and

stove pipe in the middle of the nave, the Pettus

memorials either side of the chancel arch covered

in cobwebs. It had not been used for a generation

- perhaps not even entered.

|

It was the

actions of the Norwich Society that prompted a more

significant use, and in 1952 it became the central

headquarters of the Norwich Scouts and Guides movement. A

brutal modernisation carved up the interior in the most

unsympathetic way, with a floor supported by metal

girders to separate the upper nave from the lower, and

the chancel arch filled in. Beyond it, offices and

toilets on two stories filled the former chancel, with a

major access staircase at the west end. The lower floor

became the headquarters and hall of the scouts and

guides, while the upper floor became a scout shop, the

Outdoor Centre. These have all now closed, and the scouts

and guides have gone.

|

|

|

|

If

you had not seen it from the outside, you would

not know that you had entered a church. The space

you enter is the lower half of the nave, a low

roof and girders above you and the chancel arch

beyond blocked up. However, its former space is

flanked by the two remarkable memorials. On the

south side is Thomas Pettus, mayor of Norwich in

1590. He kneels in his mayoral robes, facing his

wife across a prayer desk, their children behind

them on either side.

|

To the

north of the arch is the recumbent figure of Sir John

Pettus, his son, mayor in 1608. He looks really

uncomfortable, not least because he has his children

pressing down on him, among them in the recessed arch

above Sir Augustine, his son, with wife Abigail. They are

all the more extraordinary for being boxed in and seen in

such a setting. To the north of them is an older tomb

recess, now filled in.

St Simon

and St Jude gets odder once you go out of the west

doorway and up to the first floor. This is completely

empty, but you are able to look out of the top lights of

large 15th century windows, with fragments of medieval

glass in them, including a composite of passion flowers

and barleycorns of the Norwich school. A doorway at the

east end takes you through the top of the chancel arch,

and once you are in the top of the chancel, the

partitions intersect and cut through memorials and other

features that once towered into this roof space - half a

19th century memorial here, a corner of an 18th century

one there, and roof corbels of angels and saints who look

on patiently while you reach out and touch them. It is

surreal, and the great 14th century window at the east

end only adds to this.

That St

Simon and St Jude survived thus far is a miracle. Empty

again, the building is undergoing a major restoration.

And now there is a chance for a new use that will rip out

the rubbish and restore it to something like its former

glory.

Simon Knott, November 2005

|

|

|