| |

|

St Peter

and St Paul, Oulton

|

|

The

area between Aylsham and Holt can seem among the

most remote in Norfolk, a landscape of scattered

villages unknown to the busy traffic a few miles

off on the Cromer road. Here, grand houses still

stand among woods and fields, and a lattice of

undulating lanes still bears mute witness to the

pattern of the past. At a lost crossroads where

four deep cut narrow roadways meet is St Peter

and St Paul, not far from the great Hall. Elms

and oaks are all about, their treetops restless

on this late summer day. When the wind drops, you

can hear a car approaching from miles off - but

not many come this way. The

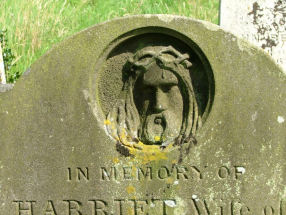

peaceful churchyard is a pleasant place to

wander, and there are several interesting 18th

and 19th century headstones. The church is small,

and has two curious filled-in archways, one on

each side, halfway down the nave. It seems there

were once transept chapels, or even perhaps this

church was cruciform, except that the roofline

must have been very low. There was a fairly

restrained 19th century restoration, which has

left the curiosity of a terracotta carved and

cusped archway to the priest door of the chancel.

Inside, the Victorian

benches have been replaced by modern chairs, and

I think this always looks good in a medieval

church. There is a plainness that offsets the

medieval survivals nicely - notably, the lower

part of a St Christopher wall painting, the fish

still swimming about oblivious of the passing of

time.

|

| There is a plain font

reset on a pillar which is rather too wide for

it. The whole piece is characterful. There is a

gorgeous little piscina, with delicate carvings

in the spandrils of the arch. Little things that

please, and the simplicity of the Sarum-screened

altar is pleasing too. There is a real feeling

that this is a church of the common people, a

building that has overseen the quiet lives of

generations of ordinary Oultoners. |

|

|

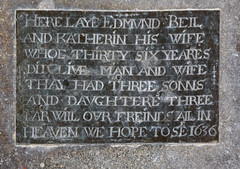

A moving testament to the people of

the past is a brass plate set below the chancel arch. It

dates from 1636, right on the eve of the Commonwealth,

and records that:

HERE LAYE EDMUND BELL AND

KATHERIN HIS WIFE

WHOD THIRTY SIX YEARES DID LIVE MAN AND WIFE

THEY HAD THREE SONNS AND DAUGHTERES THREE

FARWILL OUR FREINDS ALL IN HEAVEN WE HOPE TO SEEThe

inscription is harshly carved, and although the

sentiment is touching, you might imagine from

their poorly-spelt little ditty that the Bells

were rural oafs from the outback. In fact, they

were people of consequence - Edmund's grandfather

had been Speaker of the House of Commons under

Elizabeth I. Further, this crude memorial was

produced at a time when the Renaissance was in

full flower in continental Europe. A telling

reminder of the price the English paid for

Puritanism, and the protestant tradition would

continue to hold strong in this backwater over

the next century and more, as witnessed by the congregational chapel of 1728 in

the narrow lanes to the north-west.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, December 2017

|

|

|