| |

|

St Mary

Magdalene, Pulham Market

|

|

The

two large villages known as the Pulhams sit to

the east of the main road between Ipswich and

Norwich, and Pulham Market's name tells us that

the citizens of the earlier of the two, Pulham St

Mary, established a trading centre a mile or so

distant on the road which grew into a second

village. The centre of Pulham Market is a

satisfying piece. The village green is wide

without sprawling, and two old inns face each

other across it. Behind one is the church, with

its powerful 15th century tower. The inns, and

many of the other houses, date from the 18th and

even 17th centuries. Chocolate box scenes like

this are rarer in East Anglia than you might

think, and no one would seriously think of Pulham

Market as a town today. But the green was the

former market place, and as the name suggests

this was a market town from the 12th century

until well into the 17th century.

There

was a railway station, but the line has now gone,

and the main Ipswich to Norwich road now bypasses

the village. For most people, their abiding image

of the Pulhams will be the old workhouse, now

converted into flats with a garden centre

surreally in front of it, on the A140 to the west

of here.

|

St Mary

Magdalene is a big church, a town church. Externally, it

is hard to see anything that is not late-medieval, and

this building would look quite at home in the centre of

Norwich, perhaps somewhere along St Benedict's Street.

Entering into the spirit of the the thing, the Victorians

treated St Mary Magdalene to an overwhelming restoration

in the 1870s. They don't seem to have touched the

structure much, and just about all the money, £1,800,

went on internal furnishings. Pevsner quotes this amount

from Kelly's Directory with one eyebrow raised, because

it is about £350,000 in today's money, which is not much

to pay for rebuilding an aisle or a tower, but buys an

awful lot of Minton tiles and pitchpine benches at a time

when, it is worth recalling, labour was very cheap.

The

niches that flank the west window and door of the

tower appear to have their original statues in,

albeit too worn away to be certain. It appears to

be an Annunciation scene. As at Pulham St Mary,

there is a grand early 16th century porch - not

as ornate as the one in the sister village, and

on the north side this time. A curiosity is that

the large east window of the porch lights

directly into the west end of the north aisle.

This would seem to suggest that the porch

predates the aisle, but it is so late that it is

hard to think that there would have been time to

build it before the Reformation set in. As we

will see inside, the arcades have little to offer

on the subject. Perhaps the window was an attempt

to lighten what is a fairly dark interior. Today,

some panels of medieval glass have been reset

among frosted quarries, better than it sounds but

difficult to photograph without through light.

You step into a large, slightly anonymous

interior, a town church. And then, the surprise

of those arcades. The most western bay of the

south side is rounded, and then it leaps away

eastwards with pointed arch. The north arcade

columns are fuller, with four shafts each, and

may postdate the porch, or may not. A pleasing

mixture, which lightens the sense of an

off-the-shelf design. The font, at the west end,

may help explain some of the cost, as it is a

fabulously ornate Victorian piece, somewhat in

the style of that at Norwich St Lawrence, with a

castellated rim. |

|

|

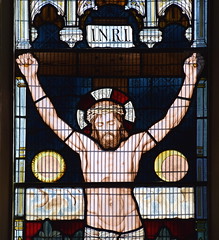

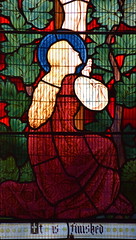

As well as

the big 1870s restoration, throughout the 19th century,

and well into the 20th, fabulous money was being spent

here on glass of the highest quality. The very earliest

is in the east window, and yet this is still as late as

1873. The work of Henry Holiday for Heaton, Butler &

Bayne, it depicts three scenes in the life of St Mary

Magdalene. In the centre, she sobs at the foot of the

cross. On the north side she washes the feet of Christ,

and on the right she returns to the upper room to tell

the disciples that the tomb is empty.

The best

of the rest of the glass is in the south aisle. An oddity

is the east window here, an Adoration of the Magi scene

which appears to be the work of Henry Holiday for Powell

& Sons, but instead of the pre-Raphaelite colouring

you might expect it has been rendered in sombre browns.

Birkin Haward thought it was 'dreary', and it isn't

helped by the nature of the stone guard on the outside.

The lovely Annunciation scene to the south of it is a

later work of the same workshop, while the angels at the

west end appear to be another Henry Holiday design,

probably for Powell & Sons.

The most striking feature of the Victorian restoration is

the vast mural above the chancel arch, depicting the

Ascension, an awkward subject. In medieval times, it was

conventional to portray it as the gathering together of

the Apostles, who pray and look upwards, prefiguring

Pentecost. Christ's feet in the clouds above would remain

to remind us of the incarnational nature of the story.

The Victorians preferred to show the whole body of

Christ, with the Disciples marginalised. Perhaps they

were uneasy with the Catholic feel of the traditional

iconography. Whatever, it is hard to show a man ascending

with dignity, even the Son of Man, or especially so.

Should he flap his arms? Should he look downwards at his

followers, or upwards at his destination? As so often,

Pulham's Ascension looks like nothing so much as a robed

figure trampolining. Thankfully the restored canopy of

honour in the roof to the west of it, shows the

Victorians doing a much better job of seeming

convincingly medieval.

Simon Knott, August 2018

|

|

|