| |

|

All

Saints, Rackheath

|

|

It

did not help that I came here on one of the

gloomiest, coldest days of February 2009, but

this must always seem a remote spot. And yet, it

is rather a charming one. All Saints was declared

redundant long ago, back in the 1970s, and that

should be no surprise. This is a huge parish, and

the main village it serves is more than a mile

off. The opening of a modern chapel of ease there

must have sounded the death knell for All Saints. Now, the

liturgical life of this building is over, and the

silence fills its days out here in what feels

like the middle of nowhere. In fact, we are

barely three miles from the outer edge of Norwich

suburbia, but you wouldn't know it. This lonely

little church sits on its bluff above the fields,

with only its gravestones for company, reached by

a narrow track along the edge of a field, which

peters out as it reaches the church gate.

|

And all

around the woods and fields roll, the gently hilly

landscape of the country above the winding rivers of the

Broads. The church does not seem an intrusion in this

landscape. Rather, there is something entirely organic

about it, as if it has grown from the land it serves, or

as if has been left here for us to find by a former

civilisation; which is nearly true, of course. Thanks to

the sterling work of the Norfolk Churches Trust, this

church is open all day, every day, when most around here

are not.

This must

be an ancient site. Ridges in the adjacent fields show

that there was a settlement here, probably until well

into the 19th Century, but now everybody lives down on

the other side of the Norwich to Wroxham road. Rackheath

Hall was home to first the Pettus family and then the

Straceys, and above all else this church is their

mausoleum. The first sign of this is in the graveyard,

where the Straceys' sombre matching crosses stand, fenced

off still, to the east of the church.

Nothing

much happened here in the way of building work in the

late Middle Ages, and what you see today is pretty much

all of the Decorated period. The south aisle is rather

curious, because the roofline cuts into the clerestory,

suggesting that it may have been refashioned after

medieval times, possibly to serve as a memorial aisle for

the Pettus family.

You step

into a building which is full of light, thanks to the

clear glass in the aisle and east window. Everything is

white and clean; and, ironically, it all feels

beautifully cared for. There were large displays of red

flowers decorating the font and windowsills when I came

here on a cold February day. The interior was spotless,

unlike that of several working churches which I had

visited earlier in the day. It was breathtakingly cold,

and the great expanses of wall memorials in the aisle and

on the north side of the nave really made it feel as if

this might be the mausoleum of a lost civilisation.

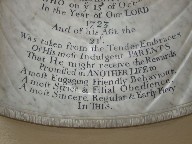

The Pettus

memorials are elegant and lovely, and surprisingly grand

in such an outpost, although they also serve as a

reminder that, until barely three hundred years ago, if

we had been here we would have found ourselves just

outside the second city of the Kingdom. The most striking

is to Thomas Pettus, who in 1723 was taken from the

tender embraces of his most indulgent parents that he

might receive the rewards promised in another life to a

most engaging friendly behaviour, a most strict and

filial obedience, a most sincere, regular and early piety

in this. From a quarter of a century earlier, but

looking the work of another quarter of a century before

that, the bold memorial to Thomas Pettus's grandfather is

a rather more serious and sombre proposition.

The

Stracey memorials are more workaday, and form a kind of

catalogue, one of the most complete records in stone of a

Norfolk family's fortunes over the ups and downs of

several centuries. Probably the most beautiful is a 1930s

monument to Mary Elizabeth Brinkley, in that flowery

development of Jazz Modern which was popular at the time,

possibly as a kitschy reaction to the severe lines of

cinemas and public buildings of the age. Noting that she

was a great-great-grand-daughter of Richard Brinsley

Sheridan, it concludes with an equally flowery

epitaph, which observes in part that from out of the

murk and mistiness of life her dreams arise, most cool

and delicate, and circle her like white and azure

flowers. This is credited to Eleanour Norton, an

obscure poet best known for the mawkish Enshrine Thy

Youth, which was popular in the years leading up to

the First World War.

Finally,

several 20th Century brasses recall the familiar

heartbreak of this intensely rural parish. Horace Arthur

Symonds of Hall Farm, Rackheath, died of his wounds

on March 3rd 1916, and is buried at Etaples near Le

Touquet in northern France. The Saints of God! Their

conflict past, and Life's Long Battle won at last, no

more they need the shield or sword, and cast them down

before the Lord. The epitaph is curiously

militiaristic, suggesting that the memorial was erected

while the conflict is still in progress, and before the

reflectiveness which followed the Armistice.

| Rather

more prosaic, and more moving because of it, are

two brass plaques by the south doorway. The first

is that to Herbert John Harmer, who died in

October 1916, and Robert James Charlish, who died

in July 1917. They were both just twenty years

old. This Monument is erected by Mr Stephen

Sutton their former employer, reads the

inscription. England Stands for Honour, God

Defend the Right. Beneath it

you'll find eleven year old Muriel FJ

Bidwell, Chorister of this church who was

mortally injured by a motor car, and entered

Paradise 10th December 1925. I knew to look

for this because earlier in the day, at another

church, I had met an old man who had grown up in

Rackheath. As an infant, he had attended Muriel

Bidwell's funeral. She had been playing in a

puddle at a corner in the road, and the car had

skidded and crushed her. The lesson of this had

obviously been made very plain to the children of

Rackheath at the time, and now in his late

eighties he had never forgotten it.

|

|

|

|

|

|