| |

|

St Mary,

Redenhall

|

|

I

had not been back to Redenhall for ten years, but

its great tower is unforgettable, rearing out of

the rolling hills to the north of the Waveney. As

you get closer, you see that spreading beyond the

church is what must be one of the largest

churchyards in Norfolk, and there is a reason for

this. Although Redenhall is a tiny village, the

parish includes the pretty market town of

Harleston, from which it is separated by the

horrible Diss to Yarmouth road. Harleston has a

19th century chapel of ease in its centre, but

when you see St Mary even from a distance you

know that this is the one that means business.

Reminiscent of the towers at Eye and Laxfield

over the Suffolk border, the tower was almost

certainly the work of the same masons. It was

bankrolled by the De la Poles, one of the richest

families in East Anglia in the 15th century, and

the fact that the elaborate flushwork is only in

three sides of the tower, but not on the south

side which cannot be seen from the road, shows

that they were a pretty wily bunch when it came

to splashing the cash.

|

The De la

Poles had been beneficiaries of the pestilences of the

previous century, when the deaths of roughly half the

people of Norfolk and Suffolk resulted in the break-up of

the old estates and the rising of wages and prices,

enabling those with money to buy land cheaply. This

emergence across northern Europe of a property-owning

independent middle class without historic ties and

loyalties to their parishes and people would inevitably

lead to the continent's two great ideologies of the

second half of the millennium, Protestantism and

Capitalism.

But that

was in the future when the De la Poles and fellow

proto-capitalists the Brothertons were making bequests to

rebuild St Mary. Up went the tower and the clerestory,

and the aisle windows were all replaced in the fashion of

the day. Only the chancel was left looking rather mean

and slight. Perhaps they would have got to that too had

priorities not changed. Around the base of the tower you

can see their leopard and wild man symbols. You might

also spot tortoises, for this was the symbol of the Gawdy

family. One curious detail is the carving of farriers'

implements on the west door. These have been taken to

mean that the door was paid for by the local farriers'

guild, but I see no reason to suppose that the carving is

contemporary, and I think it is as likely to be the work

of an idle 18th century hand.

Redenhall church is famous for one particular medieval

survival. This is the spectacular double-headed eagle

lectern, the glorious product of a 15th century East

Anglian workshop. There is another in one of the Kings

Lynn churches, and the one at St Mark's in Venice is said

to be from the same workshop. I love the little lions on

the pedestals best of all. Remarkably, the church has a

second medieval lectern, a wooden one, and both are

solidly chained down to prevent theft.

Inevitably,

the interior of the church is not going to live up to the

exterior. Today, I had come here from the two churches of

the Pulhams, both huge barns of churches, and this one is

a bit of a barn too, vast and echoey, but perhaps a

classier barn than the two I had previously visited. It

is true that the inside of St Mary has been thoroughly

Victorianised, and it is really hard to summon up any

sense of its medieval life. The serious dark woodwork of

the case of the Holdich organ in the west gallery would

have frowned on the acres of coloured glass in the naves

at the Pulhams, but here there is relatively clear light

with only a few Ward & Nixon windows that can easily

be tuned out. The best glass is in the chancel, the early

20th Century east window by Herbert Bryans to the design

of Ernest Heasman. They worked together elsewhere in

Norfolk in the north transept at Salle, and on the east

window at Holt which is broadly similar to this one. The

other glass in the chancel is of the 1860s, by Thomas

Baillie.

There are

interesting corners which give the church very much a

character of its own, for example the Gawdy chapel at the

east end of the north aisle which contains a spirited

classical altar tomb of the late 18th century, a hint of

Strawberry Hill Gothick about it, rather unusual but very

well done.

The

window of heraldic glass is by Samuel Yarrington,

and is said to have come from Gawdy Hall in the

north of the parish, demolished in the early

years of WWII. An intriguing detail in the Gawdy

chapel is a 16th Century Venetian linen chest

which is also said to come from Gawdy Hall. It

stands open, and you can see a depiction of the

Annunciation with sailing ships above on the

inside of the lid, which is at once very curious

and rather lovely.

You can walk around the great organ to beneath

the tower, an impressive space as large as some

churches. Though the west doorway is no longer in

use, you get an impression of the great

processional entrance this must once have been,

and perhaps an inkling of what St Mary was like

in its late medieval heyday, a place at last to

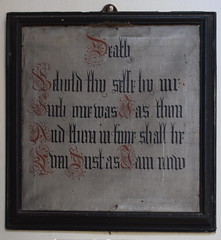

reflect on the glory that once was here. As if to

remind us of the passing of all such things, a

surviving painted plaque, probably from a lost

17th Century memorial, hangs beside the tower

arch. Death, it reads, behold thy

selfe to me, such one was I as thou, and thou in

time shall be even dust as I am now...

|

|

|

Simon Knott, August 2018

|

|

|