| |

|

All

Saints, Roydon

|

|

Not

to be confused with the Roydon near Diss, this

little village sits out in the mazy lanes to the

south of the Sandringham estate. Like many around

here, the church is kept locked, but there was a

keyholder notice, and also a very affable old

gentleman who was happy to lend me the key. The

church sits back from the lane, and your first

impression is of the solid 14th Century tower,

and then the sequence of curious round-headed

windows picked out in polychromatic brick down

the north side of the ashlar nave. There is a

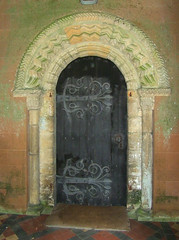

surviving Norman doorway on the north side, and

an even better one in the south porch. On the

doors themselves, the ironwork is flourishing but

not ornate, and what strikes you is the sheer

quality of it. Surely it is not the work of some

simple village blacksmith? The answer

is no, it almost certainly wasn't. The tower

survives from a medieval predecessor, but the

rest of the church was entirely rebuilt by the

young George Edmund Street in 1857. This is

interesting for all sorts of reasons. At the

time, Street was making a considerable name for

himself. He had worked for five years in the

office of George Gilbert Scott, carrying out his

own commissions, including entirely new churches

as well as restorations, mainly in Cornwall. An

enthusiast of the Ecclesiological Revival which

had inevitably followed the wave of excitement

created by the Oxford Movement, Street was

appointed Diocesan Architect to the Diocese of

Oxford in 1850. He was just 26 years old.

|

By 1855,

his increasing reputation enabled him to set up in

practice for himself, in London, and he entered designs

for a number of competitions for secular buildings in the

city that were going up in the new gothic style. Mostly,

he was unsuccessful, but one of the first churches he

received a commission for as an independent architect was

this one, All Saints at Roydon.

Now, we

think of Street as one of the half dozen top architects

of the Gothic Revival, so it comes as some surprise to

discover that All Saints was rebuilt in a neo-Norman

style. But this was just a year or so after the

publication of his book The Brick and Marble Architecture of

Northern Italy, so perhaps his mind wasn't yet fully

focused on the pattern-book English gothic of his friend

Butterfield's All Saints Margaret Street. Pevsner seems to

think that Street would have been reluctant to essay into

neo-Norman, but if he was, he made a pretty good job of

it.

There is a

pleasing harmony to the building, the details taking

their key from the surviving doorways. The glass of

Clayton & Bell (east), depicting the Crucifixion

flanked by the Resurrection and the Ascension in three

lancets with a roundel of the Nativity above, is an

unusual choice for neo-Norman, but once again it works

very well, as does the west window depicting St Peter and

St John, which Mortlock thought was probably by William

Wailes. The font is grand, the pulpit, albeit in wood,

echoes the neo-Norman style of the building. It should

all be terribly kitschy, but somehow the quality of the

work shines through, and there is a quiet gravitas to the

interior that I had not expected. Is there a reason for

this?

Well,

perhaps there is. In January 1856, Street took on as an

apprentice a maverick genius by the name of William

Morris. The 21 year old Morris was just down from Oxford,

where he had studied classics, but his real interest had

been in medieval art and architecture. He had known the

older Street in Oxford, and shared his passion for the

work of Pugin and Ruskin. Morris's arrival must have been

like a firework going off in Street's office. His

obsession with detail, his puritanical rejection of

mainstream artistic tastes, his dislike of urban life and

his longing to return to the idyllic simplicity of

medieval rural life and manners - is it wishful thinking

to see these things reflected in Street's All Saints,

Roydon? At the very least, can we assume that the

ironwork of the doors may have come from Morris's

influence, and possibly even his design?

| Morris

did not stay with Street for long, for soon his

obsessions were all consumed by the

Pre-Raphaelite Movement. He would never complete

his apprenticeship. But for a year and a bit, two

of the great figures of 19th Century art and

architecture were working together here at lonely

Roydon All Saints, an extraordinary thought. Both Morris

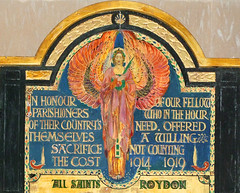

and Street were long in their graves when the

final little touch which makes Roydon All Saints

even more special was installed. This is the

First World War memorial board. Probably by a

local hand, it has been painted vividly in a

pious 1920s style at the point where late Art

Nouveau is tipping into Art Deco. This kind of

folk art is a precious touchstone down the long

generations, to be treasured and preserved. A

great angel, a crucifixion and a couple of

haunting little vignettes of soldiers flank the

names of the five boys who never came back.

|

|

|

|

|

|