| |

|

St Peter

and St Paul, Scarning

|

|

Most

East Anglian churches are open every day, but

there are sticky areas and this is one of them.

At least Scarning church has a keyholder now,

although the process of obtaining the key was

somewhat convoluted, mainly because the natives

were so friendly. The keyholder was out, but a

man in the street directed us to where he thought

the keyholder might be. It turned out that he

wasn't, but a lady there pointed us in the right

direction. The keyholder was a very affable chap,

although he was at pains to make sure we didn't

see where he took the hidden key from. However,

when we took it back he quite happily replaced it

in its hiding place while chatting to us, so

either we looked decidedly dodgy when he first

set eyes upon us, or he forgot that he was meant

to be keeping it a secret. But I digress. Scarning

church sits on the main road into the town of

Dereham ('The Heart of Norfolk!') but it

is an attractive church despite the busy road,

and there is an intriguing two-storey transept to

the chancel. Mortlock dates this to the 1570s,

the lower storey a vestry and the upper storey as

a residence for the minister, and it does have

the familiar Tudor look about it, although I'm

not convinced about the residence. A schoolroom

seems more likely. Pevsner went for the 19th

century restoration of the chancel, pointing to

the slightly odd tracery of the east window as a

companion piece, but his revising editor Bill

Wilson has put him right on this..

|

The tower

is dated by successive bequests to the very eve of the

Reformation - and then almost beyond, because Bill Wilson

notes one Thomas Secker leaving money in 1547 as a

bequest as the new werk goethe forwarde on the tower.

Presumably the death of Henry VIII that year put an end

to this, as the protestant reformers' gloves came off,

and bequests became a subject of suspicion of idolatry.

You can easily imagine that his widow had Edward VI's

Thought Police knocking on her door as her husband looked

down in distress from purgatory. Heartless times.

The most

striking impression on stepping into the church is of the

clear, wide, light nave, with a shadowy chancel beyond.

It is an attractive juxtaposition. The 13th Century

square font shows the flourishing of English art as we

moved out of the Norman period. Its cover is a

beautifully colourful piece, mostly 17th Century I should

think, though there are later elaborations. The east end

of the nave is beautifully done, with red and white

chequerboard paving and a big holy table serving as the

nave altar.

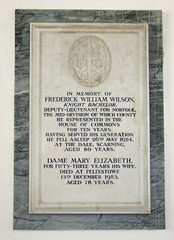

| The

lectern is a curious piece, at once rustic and

elaborate with its gothic tracery and

cartoon-like figures of the orders of the church

around its base. Behind, the chancel's gloom

beyond the screen is an atmospheric backdrop,

full of mystery. The screen is a good one, the

upper parts as bubbly as lace, the whole thing

recoloured dramatically. The sanctus bell is

still in situ on the south side, although this is

probably a modern reconstruction. You step

through into the chancel which owes all of its

presence to the windows of William Wailes, that

mid-19th Century master of shadowy stained glass

intricacy. Enthusiastic Latin scholars

will be detained for more than a while by the

elaborate inscription to Maria Burton, who died

on New Year's Eve 1710. The brass on which it is

inscribed looks as if it might actually have been

a coffin plate. Nearby, the memorial to Edward

Games, an infant sonne of John Games of

London Esq who died 14 Maii 1623, features

the little fellow lying in death, his head on a

skull. He was just twelve hours old. Beneath him

is a funerall elegie on the death of Edward

Games, a long and elaborate tribute to one

so tiny. O cruell fate that robdst a doleful

mother!

|

|

|

Simon Knott, May 2015

|

|

|