| |

|

St Peter

and St Paul, Shropham

|

|

Shropham is a largish

village on the edge of the Breckland, not far

from the Gallows HIll interchange on the A11, but

with the water meadows of the young River Thet

keeping the modern world at arms length. The

parish was a large one for the Brecklands in

medieval times. Shropham Hall is a good mile off,

as close to Great Hockham as it is to its own

village. And Shropham's church of St Peter and St

Paul is big too, an imposing and substantial

structure, its tower from the early 16th Century

and its nave substantially of the late 15th

Century, but still bearing the marks of the Early

English church it replaced. The north doorway

probably says something of the scale of the

earlier building, as does the pretty clerestory

of quatrefoils. Now,

they are overwhelmed by the huge Perpendicular

chancel, which screams late medieval wealth at

you. Just on its own it would be bigger than many

Norfolk churches. In fact, it was substantially

redone in the 19th Century, but probably as an

accurate copy of what was there before if the

scale is anything to go by, and as for that

magnificent east window, if it isn't the same as

before then I'm sure we won't mind. The

churchyard is also suitably large, with a modern

extension to the west, and pleasingly

disorganised. Here the Shropham dead lie, down

the long generations.

|

Inevitably,

with such a large chancel and low clerestory, the eye is

drawn to the great east window on entry. All this was

intended. By the 15th Century there was a move away from

the shadowy, mystical worship and private devotions of

the previous centuries. The Priest came down out of the

chancel to his pulpit, and made the nave his own. Benches

were provided to encourage a more corporate attitude to

Mass, an enforcement of Catholic doctrine, the beginning

of congregational worship. The building filled with light

from the east, cool, clear and rational. The Reformation

was less than a century away.

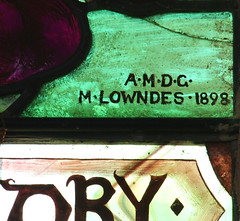

Quite the

most eyecatching things about St Peter and St Paul,

however, both date from the 20th Century. They are both

windows. The most interesting is that on the south side

of the chancel by Mary Lowndes. She was one of the major

figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement, working with

such greats as Christopher Whall and creating the Glass

House Studio in Fulham with Alfred Drury, but she was

also an important figure in the Suffragette movement. It

was Mary Lowndes who designed their well-known posters,

including the ones letting the public know about the Cat

& Mouse Act. Her work can be found in half a dozen

East Anglian churches, most notably at Lamarsh in Essex

and Ufford in Cambridgeshire, where she designed full

schemes, but also at Snape in Suffolk, Linton in

Cambridgeshire and here at Shropham, her only work in

Norfolk and an early work at that. It depicts the

Adoration of the Shepherds and the Magi in an English

woodland, a fiery angel standing behind the Holy Family.

At the bottom are scenes of the shepherds in the hills

with their flocks and the wise men following the star.

The other

window, perhaps not quite so thrilling, is by Powell

& Sons and dates from the 1940s. It commemorates Flight

Sergeant Ronald Garnier, of Shropham Hall, who was Killed

in action off Gibraltar in a Spitfire 11th October 1942.

The figures of St Michael and St George flank Ronald

Garnier as he kneels to pray with his sword against a

cross, as well as scenes of the Rock of Gibraltar and

Shropham Hall, his home. The only other stained glass in

the church is a curiously unsatisfactory mid-19th Century

crucifixion in the central light of that great east

window. Were there once scenes in the other lights?

| Hanging

on the south side of the sanctuary is one of

those fascinating little survivals which help

make exploring churches so interesting. This is

the late 19th Century processional banner for

Shropham & Larling Girls Friendly Society,

which was an Anglican organisation, one of

several founded at that time of which the Mothers

Union is probably the best known today. The GFS

was intended to support unmarried girls in

service, away from home and working in big houses

like Shropham Hall. It was very common for

working class girls to go into service - my

grandmother, the daughter of a Cambridge drayman,

was a servant in a large house in Hertfordshire

as a young girl in the last years of the First

World War. But it was that War which changed the

social structure of England forever, and although

some girls would still go into service there were

no longer the great numbers of them living away

from home, nor was there any longer the

paternalistic expectation that the Church would

take care of their moral welfare, and it faded

from sight. In fact, the Girls Friendly Society

survives today, working with young women with

emotional difficulties. Nearby, the

great 18th Century wall memorial to James Barker

and his family suggests that they were themselves

probably not short of a few servants.

|

|

|

|

|

|