| |

|

St

George, South Acre

|

|

Here

we are in the winding lanes of west Norfolk, out

beyond the Swaffham to Fakenham road. Out here,

secret villages hide in folds of fields and

woods, and lanes peter out into nothingness. Of

course, it isn't all a secret. Castle Acre, for

example, is one of the best known and loved

villages in Norfolk. Its castle, priory and

church attract plenty of tourists, as do its pubs

and tat shops, but I wonder how many visitors

make it to this delightful little corner, about a

mile's walk from the high street? South Acre

is little more than a church and a few houses,

and the church is humble and homely in comparison

with the splendour and delights of the nearby

larger village. But inside this building is one

of the most atmospheric and fascinating interiors

in Norfolk, full of historical details and a

sense of the numinous. It is one of my favourite

small churches in England.

|

Externally,

the building is rather curious, its south and north sides

being completely different in character. The north face,

which it turns to the road, is organic and earthy, full

of 14th century grandeur. The south side is crisper and

of the character of the 15th century, although I suspect

this is mainly the result of 19th century restoration.

The entrance is from the north, and you step into a

perfectly rural and ancient space, with brick floors

spreading in all directions, and the rugged, primitive

Norman font topped by a 16th century Perpendicular canopy

which lifts the eyes to the beautiful hammerbeam roofs.

To the

east runs a homely, low arcade, dividing off the north

aisle. This aisle contains the most significant feature

of the church, the Barkham mausoleum of the early 17th

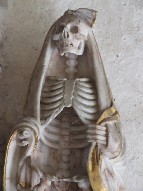

century, behind a contemporary wrought iron screen. Sir

Edward Barkham, who died in 1623, was a former Lord Mayor

of London, and the memorial he shares with his wife

Penelope is one of the most delightful in Norfolk. It was

made by the Christmas Brothers, and features Sir Edward

and Lady Penelope lying together, their heads facing

west. They are dressed elegantly in the clothes of the

day, but it is really the details of the tomb which catch

the eye: Life as a young girl, and death as a grinning,

shrouded skeleton, flank the inscription, while an hour

glass sprouts gilt wings. Below, two sons and three

daughters kneel in prayer, but they seem distracted, lost

in thought and peering around corners. Between them, a

charnel cage is filled with the skulls and bones of the

Barkham dead. The whole piece is utterly enchanting.

The

Barkhams rather steal the show here, but it is another

family, the Harsicks, whose name is found the most often.

At the west end of the Barkham memorial, within their

chapel, is a large brass to Sir John Harsick and his

wife. Harsick died in 1384, and the formal portrait of

the pair, almost life-size, is softened when you notice

with a frisson, in Larkin's words, his left-hand gauntlet, still clasped

empty in the other; and one sees, with a sharp tender

shock, his hand withdrawn, holding her hand. Then

the image becomes a perfect illustration for An

Arundel Tomb, proving our almost-instinct

almost-true, what will survive of us is love.

Another Harsick is probably the

stone effigy of a Knight Templar further west, Sir Eudo,

who is known to have taken part in the crusades. More

intriguing, and certainly more startling, is the eroded

wooden effigy, now in a tomb recess on the south side of

the chancel. On the floor nearby is another brass figure,

Thomas Leman, who was Rector here and died in 1534 -

assuming this inscription was made pretty soon after his

death, it had barely a decade to ask for prayers for his

soul before such things became illegal. Another brass

figure is in the nave, of a similar date. There is a

simple engraved brass of the Blessed Virgin and child, a

rare survival; I only recall seeing this twice elsewhere

in East Anglia. These, taken with the inscription on the

font cover which asks for prayers for the soul of

Geoffrey Baker in 1534 suggests that, in the last gasp of

Catholic England before the Reformation, a large amount

of money was spent here at South Acre.

| There

is a smattering of medieval glass in the north

aisle, and bench ends which are probably a

century earlier than the font cover. But even if

it was not for these, the utter charm of this

pretty interior would be enough of an enticement.

And little details that speak of the care of

centuries past; the stone memorial in the chancel

wall tells us that, in August 1725, the Reverend

Mr William Brocklebank new pavid this chancel

with stone at his own charge, had the gravestones

clean'd and laid even, removid none that had any

inscription, but gave three plain ones to be laid

in the body of the church. There are ledger

stones in the north aisle to an 18th century

Rector, George King, and his relict

Elizabeth, and pretty bench ends carved by an

early 20th century successor, including a snail,

a frog and a fish. It all builds to a harmonious

whole, the perfection of a gorgeous, rustic

little village church, the slowly beating heart

of its parish. |

|

|

|

|

|