| |

|

St Peter

and St Paul, Swaffham

|

|

Swaffham

is the most elegant of Norfolk's smaller towns,

and, architecturally at least, its parish church

is one of the great East Anglian small town

churches, to be mentioned in the same breath as

the likes of Dereham and Mildenhall. It sits

close to the western edge of its churchyard, a

passageway leading through from the west doorway

to the market place, a pleasingly organic

juxtaposition. The glory of St Peter and

St Paul is the tower, which went up early in the

16th Century on the eve of the Reformation.

Another twenty years or so and it would not have

happened. Like that at Cawston, it is built of

rugged Barnack stone, and is elaborately

decorated with symbols, most notably the large

wheels containing the crossed keys of St Peter

and the crossed swords of St Paul, which appear

around the base course. There are blank shields

between them, and the whole base course was once

perhaps painted.

|

The lead

and wood fleche on top of the tower is 19th Century, but

it replaced a similar earlier structure. There are aisles

and clerestories to north and south, as well as a large

transept chapel on the south side. The churchyard

stretches away to the east, with no shortage of good 18th

and 19th Century headstones, a suggestion of quite how

wealthy this town has been over the last few hundred

years. You enter the church through the great west

doorway, one of the grandest entrances to any Norfolk

church, and the sheer bulk of the building spreads out

before you. This is a church which seems larger inside

than out. The space is topped off by a fine late medieval

angel roof, which is said to be chestnut (although I have

heard of several medieval chestnut roofs in East Anglia

which, on proper investigation, turned out to be oak

after all).

Perhaps

inevitably, St Peter and St Paul underwent as extensive a

restoration in the 19th Century as any small town church,

giving it an urban and somewhat anonymous character

inside. Nevertheless, there are some good early

survivals, the best of which are perhaps the figures on

stalls in the chancel which peer out, rosaries in hand,

presumably 15th Century donors.Opposite them is a large

19th Century bench end of man and his dog, the Pedlar of

Swaffham, of which more in a moment.

The story

of the Pedlar of Swaffham is interesting, because it

relates to this church as we see it today. In the legend,

John Chapman, the pedlar in question, learns of the

whereabouts of a large sum of money in a dream, finds it

and gives it to provide the church with a north aisle and

the magnificent tower. Interestingly, the upper lights of

the north aisle are now filled with figures in 15th

Century glass, some of which are angels, but some of

which are clearly donors. There are more medieval panels

in the west window.

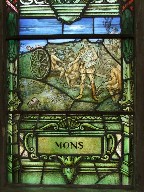

The

best-known glass in the church, however, is modern. It is

in the south transept, the former chapel of the guild of

Corpus Christi. This is now the WWI memorial chapel, and

its main feature is a large window by William Morris of

Westminster. The four main figures are St George, St

Martin, St Michael and the Blessed Virgin, but perhaps

more interesting are the smaller panels at the bottom,

which depict the fighting at Zeebrugge, Jerusalem and

Mons, and a scene inside a field hospital. The archangel

Michael is shown above the scene of Mons, on the Western

Front, where it was widely believed at the time that a

host of angels had led the British troops into battle.

John

Botright, the 15th Century rector of the church who

oversaw the late medieval rebuilding of the nave and

chancel, lies in effigy on the northern side of the

sanctuary. Unfortunately, he suffered the ignomy of

having his tomb canopy lowered by the 19th Century

restorers. The jagged cusping of the arch comes down to

just above his body, to the extent that it looks as if he

is being eaten by his own tomb. In the south aisle chapel

lies Katherine Steward. She died in 1590, and now kneels

piously regarding the modern sanctuary furnishings,

holding a huge and hideous skull in her hands. What gives

her added significance is that she was Oliver Cromwell's

grandmother. More alarming even than Katherine Steward's

skull is an inscription on a modern brass nearby to

the Splendid Memory of Harold Frederick Ellwood Bell ICS,

who was killed by a tiger in 1916 while

safeguarding some of the natives of his district. I

assume that he suffered this fate in some far-flung

corner of the British Empire rather than unexpectedly in

a local field - although, of course, strange things do

happen in Norfolk.

|

|

|