| |

|

St

Margaret, Swannington

|

|

Swannington

sits in the hills above the Norwich to Fakenham

road, a large village in woods and fields, higher

than its near neighbours Alderford and

Attlebridge. Not far off are giants: the churches

of Salle and Cawston are visible as sentinels

from the ridge a mile or so to the north. But

here we are still settled in wooded lanes, and St

Margaret is a big comfortable church that seems

to have relaxed, sprawling in its wide graveyard

at the highest point in the village. Most

striking, of course, is that massive tower, quite

unlike the erect pencil-like beacons of

Attlebridge and Alderford. It is as if the

medieval stone masons delivered the materials for

all three towers to this church by mistake, and

then used them all here. Successive restorations,

including a fairly big 19th century one, have

enhanced it, and here it sits, flanked by its

aisles, as fat as butter on a mound of green

velvet.

And

perhaps a reminder that we are close to some of

England's greatest churches is the magnificent

south face of the porch. The porch itself is a

functional, perfunctory one, and presumably this

facing was onto an older structure. In stone and

flushwork above the door are the words IHS

NAZARENES ('Jesus of Nazareth'), and there are

flushwork monograms about the base.

|

Best of

all, in the spandrels, are two carved scenes. The one on

the left shows a very fat dragon, with two bemused

onlookers. On the right hand side, the dragon is dead,

the people are happy, and an armoured female looks

triumphant. These are scenes in the life of St Margaret,

an unusual thing to find, although the same two scenes

may be on the screen at nearby Weston Longville.

Because

the aisles extend to the western face of the tower, and

the area below the tower is open, the west end of the

church is wide and high, creating the sense that this

will be a bigger church than it actually is. The war

memorial is set in the middle of the west wall. Turning

east, The building opens out into its aisles and then

narrows again for the tall chancel. The interior is

rather dark, because there is no clerestory, and the

richly coloured glass of the east window is jewel-like in

the gloom.

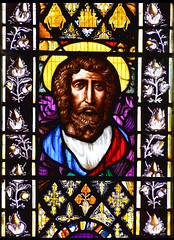

The whole church focuses on the collection of glass in

the east window, featuring heads of flowers with

exhortations to Seek the Lord and Watch and

Pray. It is rich and intricate, as if this was the

side chapel of a French cathedral, and it was intended

for contemplation. In fact, apart from the two heads of

Christ, it must all have come from a domestic setting

originally.

There are

a few intriguing medieval survivals. The chancel roof is

original, late 15th century. A crowned Norfolk angel

plays the harp cheerfully high up in a west window. The

purbeck marble font, probably 13th century, has been

cobbled together with marble legs by the Victorians.

| Best

of all is the Norman pillar piscina in the

sanctuary. Supposedly, it was 'found' by the

Rector in the rood loft stairway in 1917. The

date alone makes this unlikely, and It probably

didn't come from here originally (there is a 14th

century one set in the wall behind it) but it

features exquisite carvings, including St George

killing a dragon. In church exploring terms

this is not a major interior, particularly in

comparison with some of its near neighbours, but

it has great local character and, despite its

Victorian going over, something of the flavour of

the self-important 18th century, when the nation

was ruled from the pulpits of the parish

churches. As if to remind us of this, Jonathan

Bladwell gave the royal arms of George III in

1762, and signed them too.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, March 2006, updated March

2018

|

|

|