| |

|

St

Clement, Terrington St Clement

|

|

I came back to Terrington

St Clement on a bright day in the hot summer of

2016. It had been a very pleasant bike ride from

Downham Market through many of the churches of

the Norfolk marshland, almost all of which are

open these days. But Terrington St Clement was by

far the largest village since I'd crossed the

Ouse. I'm never sure

what I think of this church. One of the biggest

churches in England, so magnificent from the

outside, so entirely Victorianised inside. It

isn't that it is done badly, but there's

something half-hearted about it, not all of a

piece at all, and it is not helped by the fact

that the evangelical congregation here would

probably prefer to be in a big modern auditorium

somewhere.

|

Recently, they've

done something horrid to the nave floor, the parquet

flooring pasted with dark varnish that makes it look like

a school hall. And yet it is still a homely interior,

despite the vast size. But this is probably the most

architecturally important church in England which is kept

locked. The key is at the village shop. I picked it up in

the middle of the day, but I was already the third person

that day to sign the visitors book - and that's just the

people who sign the visitors book. The obvious conclusion

is that the congregation see this building mainly as a

venue for the Sunday club, and that other visitors are

merely tolerated. Mind you, the people in the shop are

very nice.

I remembered my

previous visit in 2006. Despite my natural arrogance, I

still have the capacity to be gobsmacked; this is what

happened to me as I stood in the churchyard looking at

the west front of the so-called Cathedral of the Marshes.

Of course, no real cathedral would be kept locked. This

Dec-becoming-Perp church is simply enormous, 168 feet

long and cruciform, with an elegant separate tower

sitting immediately beside it. The tower was originally

intended for the crossing, but despite massive piers

inside the builders lost confidence, and built it beside

the west front instead, probably because of the

experience of the builders at Elm, not far off over the

Cambridgeshire border, where the tower leant out of

kilter within ten years of being finished, and still

leans today. The builders at nearby Wisbech, West Walton

and Tydd St Giles got the same message. And perhaps

because of the offsetting of the tower, this huge

building is not bulky or clumsy; the clerestory continues

into the transepts, to reappear triumphantly in the

chancel, and imparts a delicacy to the vastness. Flying

buttresses, turrets and spires complete an almost wedding

cake effect.

Like many huge churches, St Clement repays a tour of the

inside before one of the outside, giving you a sense of

the soul beneath the skin, the ghost in the machine. The

south side is best, with its pyramid of windows on the

transept; the transept itself asking a few questions with

masonry appearing to be intended for a lost chapel - was

it ever built? - and some terrific 14th and 15th century

grotesques, including an imp that is the spit of Italian

TV puppet Topo Gigio. At least one of these appears to be

an image stool reset in the wall, in which case they

might all have been collected here, probably by

Victorians.

The interior can’t live up to it, being pretty much

all Victorianised, but it is still an awesome space to

wander in. This is obviously low church in character, but

I liked the way they had organised the nave so that,

despite the vastness, it is still used for worship. On

Sundays they have a central altar under the crossing, but

when the church is not in use this is moved into the

south transept (along with the drumkit) and the long

vista to the east is opened up. I think that the stepped

image niches above the crossing arch must be a Victorian

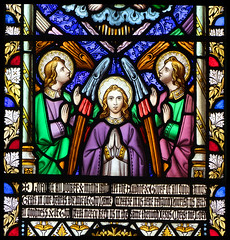

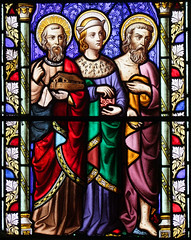

conceit. There is a good collection of early 20th Century

glass, mostly by the Powells but also by Jones &

Willis, among others, as well as some mid-19th Century

glass by WIlliam Wailes.

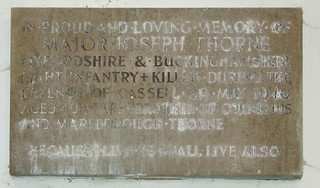

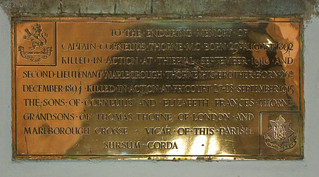

One of the

windows, based on James Clark's The Sacrifice and

probably by Jones & Willis, remembers John Henry

Brown, a volunteer with Kitchener's Army. Terrington

St Clement may be a large village, but there seems an

obscenely large number of names on the War Memorial.

There are also a number of individual war memorials

scattered around the church.

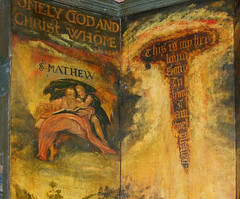

The most famous

feature is the towering font cover, which seems to have

been put together by someone very clever in the early

17th century, cannibalising something 15th century

Perpendicular and putting it over an opening stage which

is warmly painted with scenes from the Baptism of Christ

and the Temptation of Christ.Voce Pater Natus,

it says, Corpore Flamen Ave! Mortlock thought

these paintings might be Flemish panels, and not actually

intended originally for the inside of a font cover.

In common with

several churches around here, there is a Georgian screen

towards the west end of the nave, leaving a kind of

narthex behind. This has been converted into a cafeteria,

which I assume is only in use on Sundays. There are

massive decalogue boards now reset in the transepts. They

are signed and dated 1635, and Mortlock thought them the

best in England. All in all, there are some wonderful

things here. And yet, there is that awful floor. A brass

plaque beside the tower arch tells us that the first

block of this floor in commemoration of the Queen's

Diamond Jubilee was laid by Mrs Marlborough Crosse,

treasurer to the Ladies Committee for Reseating the

Church on 17th August 1897. So we have Queen

Victoria to blame. I suppose it would have been too much

to hope that Elizabeth II's Diamond Jubilee might have

been celebrated by removing it.

Simon Knott, September 2016

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site.

|