| |

|

All

Saints, Tilney All Saints

|

|

West Norfolk is flat, but

without the haunting bleakness of neighbouring

Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire. To be honest, it

is all a bit too suburban to be mysterious, and

where there aren't bungalows there is an

agri-industrial busy feeling. Tilney All Saints

is unusual because it is actually rather a pretty

village. All Saints

is another very big church with an absolutely

massive tower, with as much in common with

Lincolnshire churches as it has with anywhere

else in East Anglia. The building is delightfully

sleepy; ramshackle, and looking as if it would

rather not be bothered too much. It reminded me a

bit of a cat I used to have. The spire is like

the one at nearby Walsoken, but this is a move

into Decorated, and is full of confidence. Oddly,

Pevsner refers to this as one of the C12-C13

Fenland churches with very long naves,built

when the land was reclaimed from the sea.

While it is certainly true that evidence survives

of Roman sea defences to the north of here, and

there is also evidence of late Saxon attempts to

prevent tidal incursions locally on a small

scale, it is extremely unlikely that the

technology existed in early medieval England to

reclaim land from the sea on such a large scale.

|

Pevsner is probably confusing the

Norfolk marshland with the Cambridgeshire fens, which

were successfully drained by the Dutch half a millennium

later. Certainly, this area was once under water; but it

is the rivers themselves that have turned it to land, by

bringing silt down out of Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire

and Cambridgeshire, and building it up into banks at the

river mouths. The estuary has slowly moved northwards,

but this happened long before the 12th century. We may

assume that this land was more vulnerable then to

inundation than it is today, but that's all.

The clerestoried and aisled nave speak of a familiar East

Anglian Perpendicular. The ivy on the north side is

covering windows and working its way through the north

door. You enter through the vestry, which is at the west

end of the south aisle and originally had two stories,

not dissimilar to Terrington St John. I wondered if it

had been a Priest's residence, although later I was told

that it is not medieval at all, and was a school room.

You step into a glorious wide open interior, full of

light. It is similarly ramshackle to the outside, laid

out under a fine angel hammer-beam roof. Gorgeous Norman

arcades reveal the true age of this place (again, as at

Walsoken) and stretch away to the east. The capitals

increase in elaboration towards the chancel, and then,

just before they disappear, they jump a century and

become Early English pointed arches. Turning back, you

see that they are matched by the breathtaking tower arch

- this is very much a church where the presiding minister

gets a good view.

There is a very curious font. At first sight it appears

early 17th Century, and this is the date assigned it in

Pevsner and elsewhere. Its panels include two scriptural

quotations in Latin, and two in English from the Geneva

Bible (one reads see, here is water: what doeth let

me to be baptised). One of the other panels features

a Tudor rose, Unless the font was commissioned in the

eight years between James I coming to the throne in 1603

and the Authorised Version of the Bible being published

in 1611, it may well actually be a late 16th Century

font, an unusual thing.

Slightly later is the screen, dated

1618 and turned and balustered as if for a staircase in a

country house. The chancel itself is full of the sobriety

of the early 17th century, quite at odds with the

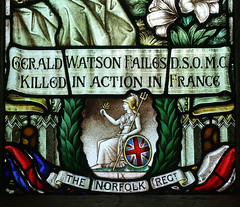

glorious arcades behind. A war memorial window features

St George and St Martin, and there is a good Queen Anne

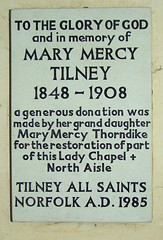

royal arms. An old font sits on the floor in the north

aisle, along with some early medieval grave slabs.

Tilney All Saints is probably less well-known than its

near neighbours at Walpole, Walsoken and Terrington; but

I thought it was lovely, a subtle and gently beautiful

place at peace with its parish.

Simon Knott, September 2016

|

|

|