| |

|

St

Margaret, Tivetshall St Margaret The area between

Diss and Attleborough is intensely agricultural. It's

hard to imagine anyone buying a holiday cottage here, or

a weekend home. Of course, a couple of hundred years ago

this was a much busier place than it is today, and we

couldn't have wandered the lanes without seeing any other

people like we can nowadays. In those days, it took fifty

people on a farm to do the work that two or three can do

today, and villages like Tivetshall supported a great

range of trades and occupations.

Norfolk villages were fairly self-sufficient, and had to

be. The decline set in after the 1851 census, the

population falling as young people set off to find

prosperous new lives in the factories of Norwich and

Ipswich. Today, the old order has gone forever, and the

few farmers that remain struggle to make a living. The

nearest shops are in Diss, and cars rule the lanes. But

I'm still pleased that there aren't many of them.

Perhaps symbolically of this new world, Tivetshall lost

its other church, St Mary, to the sonic boom of a jet

plane in the late 1940s. But the one that remains is a

jewel. St Margaret sits out in the flat fields with only

a farm for company, but its small, crowded churchyard is

well-maintained, a blanket of emerald in this ploughed

empty landscape.

I came back here on one of those stiflingly hot days of

which the summer of 2018 had so many. It was a relief

after the straight miles from Gissing to get off my bike

and wheel it into the shrouded churchyard. You approach

the building from the east, and at first sight the

chancel is curious. Its steeply pitched roof is higher

than the western part of the church. Although it is

basically early 14th Century, despite the addition of

later windows, it looks rather like a farmworker's

cottage tacked to the east of the nave. The tower is

broadly contemporary, which, as Pevsner points out, is

also curious, for a major bequest for its rebuilding was

made in 1456. The nave is clinically perpendicular with

crisp windows, so perhaps they spent the money there

instead. Certainly, the south doorway appears late

medieval, and perhaps even later than the Reformation.

This was about my half-dozenth visit, I suppose, and yet

still with anticipation I stepped through the doorway

into the small church. You can see at once that it is a

remarkable place. On an earlier version of this account I

described this as a ramshackle, cluttered and untidy

church, delightfully so, and how much I admired it for

that. I hoped that no one in the parish would have been

offended by this, but in any case this church underwent a

major restoration in the first decade of the 21st

Century, and today feels crisp and loved, though still

intensely rural, and perhaps even more delightful. It

feels like a church of the common people.

The stone floors and old woodwork of the nave set the

tone, but what most people come to Tivetshall St Margaret

to see is to the east of them. In early days, churches

were essentially two separate rooms separated by a screen

under a boarded tympanum. This is hard to imagine today,

unless you come to somewhere like Tivetshall St Margaret,

because here the chancel arch still retains its tympanum.

It is safe to say that almost all medieval churches once

had one of these, but they were mostly removed at the

Reformation because they displayed the rood, a depiction

of the crucifixion which was proscribed by the Anglican

reformers. In a few places in Norfolk, however, these

tympanum boards have survived, and as at nearby

Kenninghall and at Ludham, the tympanum here was painted

over in the second half of the 16th Century with the

state Royal Arms. This had been a decree of Henry VIII,

but no Henry VIII royal arms survive. So, the set for

Elizabeth I at Tivetshall St Margaret is one of the

earliest in England.

The boards stretch across the church, wall to wall and

from the top of the roodscreen to the roof. The lion and

the dragon flank the vast Arms, with God Save Our

Quene Elizabeth painted beneath, and a neat reminder

of who was now in charge: Let every sowle submit hym

selfe unto the authority of the hyer powers, for there is

no power but of God, the powers that be are ordayned by

God. The design includes the symbols of the other

four Tudor monarchs, as well as the badge of Elizabeth's

mother, Anne Boleyn.

Beneath

them, the Ten Commandments are rendered as a chunk of

scriptural prose. There is certainly no finer set in

England of this period. When I first saw this set about

twenty years ago it was covered in dark varnish, but this

was removed as part of the recent sensitive restoration,

and they are now as vibrant and clear as when they were

painted. We even know which churchwardens were

responsible for their construction and placement, for the

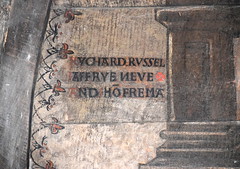

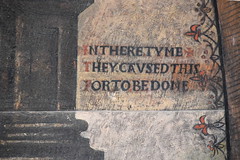

date is given as 1587, and at the sides of the tympanum

they are remembered: Rychard Russell, Jaffrey Neve

and John Freman: In there tyme they caused this for to be

done.

The screen

below is painted in red and green, with gold stencilling

and a shield depicting four magpies. Beyond, the chancel

fills with light, and a gorgeous red, green and gold

English altar, echoing the rood dado panels, is

surrounded by a Sarum screen. To the north of it is an

Easter Sepulchre that dates from the original building of

the chancel.

The church retains its medieval bench ends, which the

Victorians would surely have itched to replace, they are

in such rough condition. Perhaps this place was simply

too poor and too remote for anyone important to notice.

They are badly damaged, in most cases just the lower half

of each figure surviving. One has a small dragon cowering

at the base, and has been recorded as St George, but I

think the figure above has wings, and is probably St

Michael. Perhaps the others are Saints too, and yet one

figure has at its feet something that looks like nothing

so much as a plough. Looking closely at the others,

another figure appears to be standing among cornstalks,

while yet anouther appears to be holding a harness. They

could perhaps be Labours of the Months, and the

remarkable thought dawns that these could have been

depictions of 15th Century locals. Whatever, they must

have been wonderful in their day. There are some earthy

17th Century additions, presumably the work of a local

carpenter.

A small church, but one to spend time in. Here is the

past hanging on, a touchstone with its thread of

continuity, but also a glimpse of Norfolk just out of

sight, no electricity, no running water, no sound at all

except the birdsong from the tree-bowered churchyard

outside. Not much has happened here in the last century

or so.

I am used to coming across accounts I have written about

churches pinned up on their noticeboard, and there is one

here, but also something I had not seen before, a quote

of mine presented in isolation, as a kind of

inspirational poster if you like, which pleased me no

end. I had actually written it about another church,

Hunworth, away to the north, but it stands as well for

Tivetshall St Margaret, and so I repeat it here:

a quiet, ancient space,

prayerful and numinous,

open and welcoming,

a place to stop and step out of time

into eternity, if only for a moment.

This is a super church, full of atmosphere and with an

intense sense of its rural past. A little treasure, a

Norfolk delight.

Simon Knott, August 2018

|

|

|