| |

|

St Peter,

Weasenham

|

|

St

Peter sits hard against the busy Swaffham to

Cromer road, a landmark site for a thousand years

or more. It marks the northern end of Weasenham,

a large, straggling village divided into two

parishes, and there is another medieval church at

the southern end of the village in a slightly

more secluded setting. In days gone by, Weasenham

St Peter was known as Lower Weasenham. Both

Weasenham churches were considerably rebuilt. All

Saints, at the other end of the village, was

reconstructed in 1905, but St Peter underwent the

privilege thirty years earlier. There is a

photograph of the church on display inside which

shows it on the eve of its restoration, and in

all honesty it is hard to see much externally

which survived from that time. Even the flushwork

was reset and made crisp. The path to

the church climbs steeply from the busy road. For

many years, this church was kept locked against

visitors, but today it is open every day, and you

let yourself in through the north porch into a

warm, moderised interior.

|

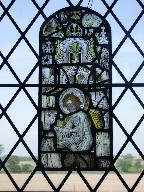

Just as

Weasenham All Saints up the road was rebuilt for Low

Church congregational worship, so this place celebrated

the Anglo-catholic tradition, and to an extent continues

to do so. And, just as the other church has one great

medieval survival in the form of its rood screen, so St

Peter has its own survivals in the form of 15th Century

glass. There is a beautiful figure of St Margaret

dispatching her dragon, and in the next window a Norwich

school angel. They were both originally set in upper

window lights, and are now surrounded by fragments of

contemporary tabernacle work. There is no way of knowing,

of course, if they came from this church originally.

Turning to

the east, you meet the delight of a splendid window by

William Warrington. It commemorates someone who died in

1849, but can it really be that early? It is full of

exuberant colour and details, and if the date is right

then it preempts much of the enthusiasms of the

mid-century Ecclesiological Movement. The central subject

is a crucifixion, the Blessed Virgin, Mary Salome and St

John looking on grief-stricken and Mary Magdalene burying

her face in her hands. The same figure of Mary Magdalene

appears to the left, an unusual scene of her pouring oil

onto Christ's feet while a po-faced Judas looks on. On

the right, rather more awkwardly, Christ welcomes the

children. Above, St Peter and St Paul in sentry box-like

tabernacles look up to the Blessed Virgin and Child. it

is remarkably early work for such Anglo-catholic themes

in early Norfolk. Above, there are angels and a shield of

the Holy Trinity. I think this window is really rather

wonderful, and appears little-known.

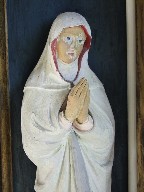

Any doubts

as to the Anglo-catholic sympathies here in the mid-20th

Century may be allayed by stepping through the curtain

that divides the south aisle from the nave. Here, the

east window is another splendid creation, this time by

Christopher Webb I think, depicting St George and St

Michael flanking the Blessed Virgin and Child. Below is a

deliciously carved and painted altar with figures

representing the Annunciation, the Crucifixion and the

Resurrection. Could it have been carved locally?

I was so

pleased I'd seen inside and it was so lovely. For years,

the Weasenham churches were a little black spot in this

area of Norfolk where pretty much all the churches are

open and welcoming, and being so close to the main road

it would be nice to think that they will be able to

attract visitors in the way that Newton by Castle Acre

does on the same road a few miles to the south.

| This

church, full of light and colour, is a complete

contrast with its neighbour up the road, but both

are fine buildings, and both welcoming. St Peter

has the edge in survivals, because it also

retains its original font, which I think is late

14th Century, its bowls decorated with

quatrefoils. Someone has later carved 1607 into

the south face, too neatly to be vandalism, I

think. Could it mark the date the font was

brought here from somewhere else? Bill Wilson in

the revised Pevsner notes that the church was

criticised for being excedinglie decaied by

the Necligence of the Propietaine in 1602,

so perhaps there was a considerable restoration

at that time. An intriguing thought, because this

would be too early for Laudian sacramentalism to

have any influence. I wandered

around to the south side of the church, where the

graveyard is wide and open. Here is an excellent

collection of high quality headstones of the late

18th and 19th Centuries, the funerary symbolism

including weeping willows, draped urns, figures

of grief, coronets, rayed books, cherubs, and the

stark reminder that the Mortal must put on

Immortality. Many are to members of the

Billing family, who were obviously a prosperous

lot. And yet, by the time of White's Directory of

Norfolk in 1845, they had all gone, and indeed it

is striking that both Weasenham churches are

relatively bereft of memorials. White does record

the intriguing detail, however, that in the reign

of Edward III, Sir John de Wesenham of this

parish was the king's butler. Being a rich

merchant in the City of London, he had the

king's crown in pawn for money advanced for the

wars in France.

|

|

|

|

|

|