| |

|

St Peter,

West Lynn

|

|

It was good to come back

to West Lynn after ten years away. Back in 2006

it had seemed a separate place, but ten years on

it was quite clear that the prosperity of Kings

Lynn was spreading westwards to grasp it

avariciously. So many east coast ports are in

decline, but King's Lynn seems to go from

strength to strength, which can only be explained

by its position on a railway line into Cambridge

and then swiftly on to London.

That day in 2006, we had driven right across

Norfolk as it was waking up on a Saturday morning

- well, a bit later than that; let's say it was

washing up after breakfast, putting its shoes on

and then going shopping. The whole of the Ouse

Valley was pouring into Kings Lynn, looking for a

parking place, and we were glad to be crossing

the river and heading into the Marshlands. First

stop was up the west bank of the Ouse, and just a

stones throw from the centre of Lynn itself.

Talking of throwing stones, West Lynn was a

fairly rough place in those days. The shop beside

St Peter had razorwire barriers like I'd seen in

the Shankill in west Belfast the previous month,

and I’d not seen so much graffiti on the

outside of a church before. The west window was

completely boarded up. |

Not surprisingly, the

church was locked, with a keyholder in the adjacent

close. He opened the door to us after about six hours and

glared out with what I took to be typical marshland

reticence. When I asked for the key, he said

“Why?” but fortunately I knew the answer to

this question, because West Lynn has a seven-sacrament

font. Knowing he’d been beaten, he gave in and

smiled, giving us the key graciously.

Coming back, the

church was still locked. But there was a different

keyholder. She was very nice, and didn't quiz me as to my

motives.

The exterior of the church is interesting. Cruciform, as

many churches are around here, the chancel is an addition

of the 1930s by the aged Walter Caroe, and looks very

much of that decade. It reminded me of Dilham. Old

tracery has been built into the walls, and the tracery

replicates the 19th century window (and contains its

glass) that once was set in the blocked chancel arch.

Despite the cement-rendering to tower and transepts,

there is a nice mix of flint and red-brick, and a little

carstone too. A 1920s vestry opposite the red-brick Tudor

porch completes the piece.

We let ourselves in to what turns out to be a very high

church – the main Sunday service still styles itself

Mass, and the Vicar is Father someone-or-other.

There’s also evidence of this in the furnishings,

including devotional statues and the like, but I didn't

get the impression that the church gets used much for

private devotions; there were certainly no candles

burning. Perhaps it is an enthusiasm of the Vicar’s

rather than of the parish as a whole.

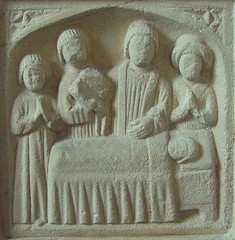

The font is a delight – probably the most primitive

of the series after Wendling's, the figures like cartoon

characters. It has been repaired with darker cement, so

you can see what is original and what isn’t, and it

is actually relatively unvandalised. The Priest hearing

confession is wearing a cowl or hood, as was the

convention of the medieval period, but in this case it

doesn't half make him look Mother Teresa. The Mass panel,

seen from the side on, is absolutely crowded with

figures, some standing and kneeling to the left of the

rood screen, which is seen end on, and the Priest

elevating the host to the right. In the Baptism panel,

the baby is held upside down. The eighth panel depicts

the Holy Trinity (not, as Pevsner has it, 'Christ

Enthroned', or Mortlock's 'God the Father').

There is a splendid

brass of a priest, Adam Outlaw (what a great name for the

fens!) and the benches are a not unpleasing mix of 15th,

17th and 19th century work, most of a local quality.

Perhaps best are some poppyheads reminiscent of those in

the chancel at Walpole St Peter. The misericords are

fascinating - they appear to have suffered the attention

of iconoclasts, but also do not seem as old as they

pretend.

The north transept is fitted out as a lady chapel, both

elegant and seemly. There is a bold squint through to the

high altar with its grand reredos. Indeed, the fittings

of the sanctuary are all boldly 20th century

Anglo-catholic, and the sedilia and piscina an exercise

in modernist devotion. The whole piece is triumphant, but

poignant too, the beleaguered anglo-catholic movement of

the CofE in its last days. It looked lovely, but it

reminded me of churches which I'd known years ago which

had since lost this tradition, which made me feel a bit

sad. Here, everything was done well, but it was fading,

and would fade out. I was glad I'd come back now.

Simon Knott, September 2016

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site.

|

|

|