| |

|

St Peter

and St Paul, West Newton

|

|

West

Newton is a pretty little village at the heart of

the Sandringham estate. When I first visited in

2006 I decided that it was the very model of what

an estate village should be. The workers houses

are fine, and constructed to a high standard.

There are workshops that serve the estate, and

one of those friendly-looking social clubs that

you get in villages around here - it is said that

Queen Alexandra disapproved of pubs, and so

Edward VII gave the villages social clubs

instead. All of this is in the Arts and

Crafts vernacular style of the day, and arranged

pleasingly around the church of St Peter and St

Paul on its mound at the heart of the village. On

that day of high summer the sky was blue, the

heat of the day hazy. From the social club, a

wedding reception spilled out onto the slopes

around the church. Children ran around playing,

while red-faced men in suits laughed and clung

tightly to their pints. On such a sunny day it

felt a privilege to be here.

|

And coming

back ten years later felt like a privilege too. Nothing

much had changed, the church still on the crest of its

cushion of a churchyard, still open. The lychgate is a

memorial to the dead of the First World War, many of them

killed on the same day. The name of Captain Frank Beck

stands out.

Beck was

the land agent on the Sandringham estate, the trusted

right hand man of King George V and a favourite of his

mother Queen Alexandra. Despite the King's protestations,

the patriotic Beck formed a 'pals company' of men from

the estate who were attached to the 5th Battalion of the

Norfolk Regiment. They sailed for Gallipolli, and they

were wiped out during the attack on Anafarta in Suvla Bay

on the 12th of August 1915.

Because

they had fallen behind enemy lines, they were listed as

missing, and a local legend grew up that they had

vanished into a mysterious cloud and were taken up out of

this world. This sounds bizarre, but it was of a piece

with legends like the Angel of Mons leading the British

troops to escape death in Flanders, and with the great

rise in spiritualism in this country in the years

immediately after the War. Perhaps it was the dust and

heat of that day which gave rise to the legend. When the

bodies were eventually found and identified, this

knowledge was kept from Queen Alexandra because it was

felt it would be too upsetting for her, and thus she died

believing in the legend. In 1999, the story of Beck and

his company was dramatised by the BBC as All The

King's Men, a horribly appropriate title. Beck was

played by David Jason.

Through

the lychgate, you come onto the wide mound of the

churchyard. The 14th century tower of the church is grand

and stately, and its solid carstone with freestone

corners looks as if it might be made of gingerbread and

icing. A beautiful contemporary image niche sits beside

the west window. The body of the church is also carstone,

built of blocks on the south side and in slipped layers

on the north, as if this was a vast dry stone wall.

You step

into a small, simple, restored church. The churches of

north-west Norfolk were in a pretty dreadful state by the

middle of the 19th century. There are more ruined

churches around here than anywhere else in England. The

purchase of the Sandringham estate by the Prince of Wales

revitalised the local economy, and his patronage led to

some pretty substantial restorations, most of which were

to a very high standard in terms of both design and

construction.

Few of the

estate restorations were more substantial than that of

West Newton. Apart from the tower, the church was almost

completely rebuilt in 1880. The architect was, perhaps

surprisingly, Arthur Blomfield, who we rarely see on such

an intricate scale in East Anglia. He was working at

Sandringham church at the same time.

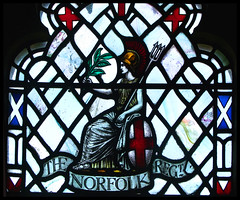

| Here,

he is at his highest, putting into practice the

future King's Anglo-catholic sympathies and

producing a very Arts and Crafts feel to the

interior, particularly with the cottage-style

windows in the aisles, with none of the

razzmatazz inflicted on Sandringham. The glass

was commissioned from Heaton, Butler and Bayne,

and although perhaps the workshop was past its

very best by the 1880s, there is a pleasing

harmony to their windows, contributing to a

quiet, intimate interior. The

intimacy of this setting is a perfect foil to the

poignant WWI memorial window of 1920 by Karl

Parsons. This depicts Frank Beck as a magnificent

St George, and remembers the men of his company. They

gave their lives for King and Country on August

the twelfth nineteen hundred and fifteen,

reads the inscription. Interestingly, Queen

Alexandra may never have seen this window, for

she became blind in 1920 and suffered severe

ill-health until her death at Sandringham in

1925. Either side of Beck are the crest of the

Norfolk Regiment and the fiery hell of Suvla Bay.

This is sad enough, but immediately beside it is

another memorial to the men killed further up the

coast at Inkerman during the Crimean War sixty

years earlier. And the men of Norfolk still had

Singapore to come.

|

|

|

|

|

|