home I index I latest I glossary I introductions I e-mail I about this site

St Peter, Wiggenhall St Peter

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England Twitter.

| St Peter,

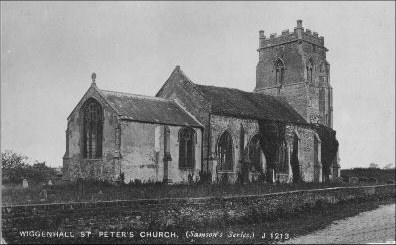

Wiggenhall St Peter The River Great Ouse rushes through Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire, sprawling before being disciplined into the channels of the Hundred Foot Washes at Erith-cum-Bluntisham. This was the Cambridgeshire parish where the writer Dorothy L Sayers grew up and where her bell-ringing father was the rector, and the river there forms the landscape of her most famous novel, The Nine Tailors. The Great Ouse spans out into other relief cuts, and for the last part of its journey it enters Norfolk as two close courses, one straight and the other wiggly, racing to the sea in competition with its cousin the River Nene which flows out of Cambridgeshire into Norfolk to the west. Between the two rivers is the area popularly known as the Norfolk Marshland, a flat and somewhat characterless sprawl of fields and nondescript villages, but a landscape punctuated by some of the finest churches in all England. It may be that St Peter was once one of them, but that was long ago. The church sits directly on the east bank of the Great Ouse, protected from it by a steep bank, and today it is a ruin. It was once fairly large, and mostly of the late medieval period. John Astyn left 20s in 1421 to the building of the chancel, and the rest of the church must have followed soon after. It is a pleasing mixture of red brick, stone facing, flint and what is probably river rubble. The south aisle was demolished in the 1840s and the arcade filled in. It was still a working church into the early 20th Century when the black and white postcard photograph near the top of the page was taken, but when Munro Cautley came this way in the 1930s he found it a roofless ruin unfortunately, for it must have been interesting. It is likely that the roof was deliberately removed to derelict the church, as was the common practice until recently when churches fell out of use, and by the 1970s and 1980s the remaining structure was completely overgrown with elder and ivy. However, this was all removed and St Peter is now a satisfying ruin to visit, for apart from the roofs and the east window tracery the structure is still complete up to the top of all the walls. The churchyard and the interior of the church are carefully maintained making it possible to wander. The original north doorway has been filled in at some point, and you enter the church through the former processional way that ran beneath the tower. These were necessary where a church stood hard against its churchyard boundary, for they enabled liturgical processions to circle the church entirely on sacred ground. There is a doorway on the west side of the tower which looks as if it might have survived from a predecessor church. The tower arch is so large that I do not think there can ever have been a door between the processional way and the nave as at, say, Combs or Ipswich St Lawrence in Suffolk, but it must always have been open. The bones of the south arcade are visible in the wall, and the aisle windows were reused when the arcade was blocked. The tracery of the windows on the north side of the nave is of an equal late Perpendicular confidence, and this must have been a grand church indeed when they were full of glass. Obviously the furnishings were dispersed long ago, but there are a fair number of survivals in stone, including two piscinas, one with a credence shelf, and dropped sills below the windows forming seating, that in the chancel marking the ghost of the sedilia. Best of all, corbels and headstops in the form of faces and beasts look down into the nave. At the time of the 1851 Census of Religious Worship this church was in a joint benefice with Wiggenhall St Mary the Virgin, and the vicar was the eccentric Richard Thomas Powell. Powell's returns to the census are the longest and most rambling of any in Norfolk, at times verging on the bizarre. You can't help occasionally wondering if he was a little the worse for drink, although Janet Ede and Norma Virgoe, transcribing the Norfolk returns for the Norfolk Record Society, politely added the annotation that the poor handwriting makes this return extremely difficult to read. The population of Wiggenhall St Peter was a hundred and sixty two, but in answer to the question asking the attendance at the morning service that day Powell answered 4 or 6, and for the afternoon sermon it was 6 or 8. Another question asked the average attendance, to which he replied none certain it is very populatius on the banks of the river across the parish almost 3 miles from the parish on the banks. The attendance at his other church in Wiggenhall St Mary the Virgin (population three hundred and twenty two) was similarly small, which he explained by replying there is a great uncertainty in the labouring as not all have been constantly resident by removing occasionally. Meanwhile the four closely set Wiggenhall parishes had between them no fewer than six non-conformist chapels, with a total attendance of more than four hundred at their main services that day. Simon Knott, June 2023 Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England Twitter. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

home I index I latest I introductions I e-mail I about this site I glossary

links I small

print I www.simonknott.co.uk I www.suffolkchurches.co.uk

ruined churches I desktop backgrounds I round tower churches